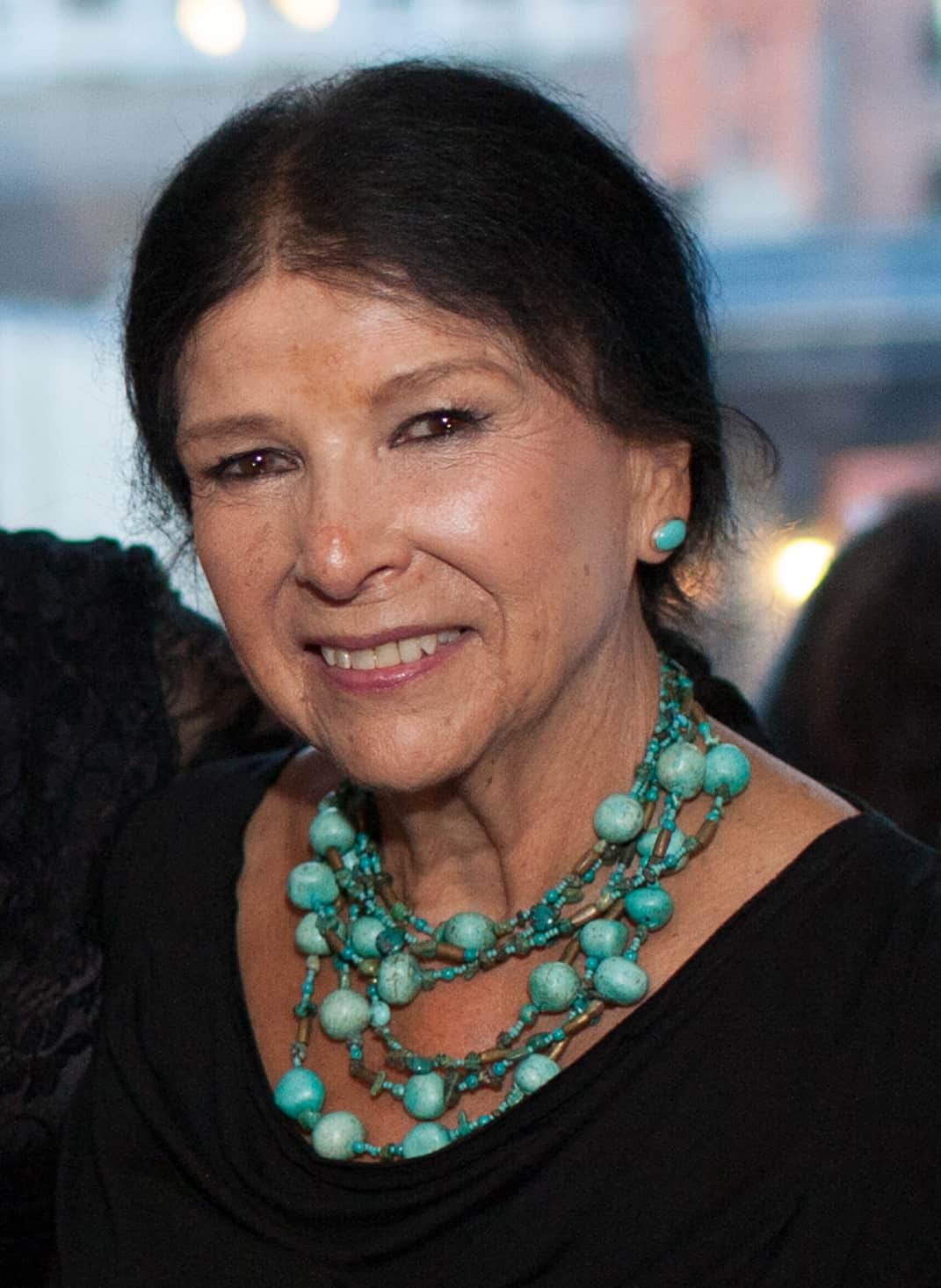

Last week, Montreal-based Abenaki filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin celebrated her eighty-fifth birthday, and on Saturday, September 9th, her fiftieth film, Our People Will Be Healed, will have its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival as part of TIFF’s Masters program. The depth and longevity of Alanis’ career is incomparable, and to say she is an accomplished filmmaker and educator would be an understatement.

Even in her old age, her drive and energy is unwavering: “My first ambition is to educate and make sure our people have a voice, our own voice.” Her latest film, which sheds light on the horrors of our country’s history, illustrates the possibility of a better future and shares a promise of hope for Indigenous youth, as well as Canada at large.

While Our People Will Be Healed offers a vision of optimism, it was the devastating tragedy of Jordan River Anderson that initially led Alanis to connect with the remote Cree community of Norway House, 800 kilometres north of Winnipeg, Manitoba. Jordan River Anderson was a five-year-old child who lived and died in a hospital while provincial and federal politicians argued about who would pay for his medical support. Alanis says, “I was going to include [Jordan] in the film, but I’m now working on a film on him alone. I didn’t feel right about it; he needed his own private story.”

Back when Alanis was advocating for Jordan’s Principle (named after Anderson and used in Canada to resolve jurisdictional disputes within government regarding payment for services provided to First Nations children), she discovered the Helen Betty Osborne Ininiw Education Resource Centre, a school that captured both her heart and imagination.

Named after a young woman whose 1971 murder was ignored and unsolved for sixteen years, the Helen Betty Osborne Ininiw Education Resource Centre welcomes students aged 4-19, and it was in these musical-filled hallways where Alanis found inspiration for Our People Will Be Healed. “We are on the road to a place we’ve never been before, to a new age for Indigenous peoples, and it is our youth who are leading us. This is what I am trying to show.”

In Our People Will Be Healed, Alanis takes us into the classrooms to observe children learning Cree from elders in the community, as well as on canoe trips, where Norway House youth bravely share their struggles and feelings. “There’s such a will to make changes and to stop the suicide epidemic,” says Alanis, who first began tracking this revival of activism amongst Indigenous youth in her 2014 film Trick or Treaty. “In that film, you see a lot of young people marching all the way from James Bay, on the Quebec side, to Ottawa. It’s wonderful to see young people realize that the way to heal is being self-sufficient, remember our history, remember our language. There’s a really strong movement right now all across the country.” She also credits the noticeable change in recent years to the fact that Canadians are finally listening.

Throughout Our People Will Be Healed, Alanis drives home the importance of storytelling and language in healing: “It’s an expression of the people, it’s inclusion…and this is where the healing is coming from. Realizing that what we are is great, which is quite contrary to how we were made to feel.” Even over a long-distance phone call, I can hear the hopefulness in Alanis’ voice: “I’m very happy I’ve lived this long to see this – the will of so many people taking their own fates and their own powers; it’s a marriage of a lot of good things and goodwill.”

With so many smiling faces and scenes of children immersed in the beauty and stillness of nature, I imagine much of the film was a joy to make, and Alanis concurs: “I loved every bit of it. We showed 500 kids playing violin! They’re so concentrated, excited and wanting to learn more instead of [being] victimized and feeling terrible about everything. [You can] see how happy the children are running into school – it’s a very special place.”

Our People Will Be Healed lays the foundation of a blueprint in which we can map out a better future for Indigenous children and youth in Canada, with the Helen Betty Osborne Ininiw Education Resource Centre being the architectural model from which to copy and build.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram