Three years ago on April 21, 2015, I was working as a TV news producer when a headline started blinking across the wires: “Accountant of Auschwitz goes on trial for the murder of 300,000 people.” It caught my attention immediately.

The idea of bringing former Nazis to court to answer for the crimes of the Holocaust is interesting for any history buff such as myself. I had also recently returned from a trip to Poland, The March of the Living, which pairs people of all ages with survivors of the Holocaust. Together, they travel to ghettos and death camps used by the Third Reich to implement the Final Solution. Staring at the shoes of dead children, and the huge mountains of hair from those who were shaved upon arrival to the camps, there seemed no doubt in my mind of any moral ambiguity. Every SS officer who participated in these crimes, even seventy years later, should pay for his role in the worst mass murder in human history.

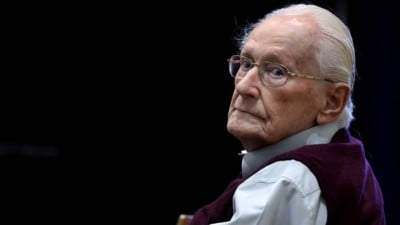

What I found, however, as I read more about this particular trial, was a tale with interesting twists that sparked questions with no easy answers. Oskar Gröning, the ninety-four-year-old former SS guard on trial, never killed anyone. As he put it, he was a mere cog in the machine. Meanwhile, most of the ideologues, the elite SS men who gave the orders to kill and were instrumental in the destruction of the Jews, went unpunished after the war due in large part to Germany’s unwillingness to prosecute their own. Now, seventy years later, most have perished but for one man who, at age twenty-one, collected the stolen loot of prisoners as they were carted off trains at Auschwitz.

Gröning came forward in 1985, standing up to Holocaust deniers in an attempt to set the record straight. He gave a public interview in 2005, believing himself to be exempt from prosecution. But in 2009, a new generation of lawyers in Germany, coupled with a change in legal thinking, meant anyone who served at a death camp could be tried as an accessory to murder. The net suddenly got much wider, and Gröning could face prosecution. His 2005 interview made prosecutors aware of his role in the Holocaust, and in 2013 they pressed charges.

Reading more about the details of this case, and the history of German trials after the war, I was convinced that a documentary needed to be made to delve into these complicated questions of law and morality. Determined to make this film, I quit my full-time job and devoted all of my attention to this project. But I had no experience in this realm. I had never made a film before.

I reached out to my friend Mathew Shoychet, whom I had met on The March of the Living, as I knew he had studied film and was as passionate as I was about Holocaust education. But he had also never made a feature film before. We needed some helping hands to guide us through this very ambitious project. By a stroke of good luck, I was put in contact with Emmy-award-winning filmmaker Ric Esther Bienstock, whose 2013 film, Tales from the Organ Trade, achieved a similar feat to the one we were trying to accomplish in this film.

In her documentary, Bienstock delved into the world of organ trafficking, a topic which, on the surface, seems to be very black and white, with the line of “good” and “evil” drawn neatly in the sand. Bienstock managed to unpack a complicated issue to expose a world of moral ambiguity and successfully challenge audiences’ previously held beliefs on this subject.

More than anything, I wanted to make a film about this trial because I myself was torn about where I stood on this issue. Gröning claimed he was just following orders. He didn’t kill anyone. But he was there. He was a witness to, and helped to run, a machinery of death that killed 1.1 million people. Who is complicit, and how far down the line do you prosecute? Had Germany gone after all the so-called Grönings–the lesser cogs–after the war, a huge percentage of the population would have been in jail. How does a country move on after a crime is committed on such a large scale by so many of its citizens?

Furthermore, does Gröning’s good deed later in life absolve him of his past sins? Does standing up to deniers right the wrongs he committed all those years ago? And will his trial send a warning to future war criminals that justice will eventually catch up to them as well? These questions are relevant now more than ever as right-wing extremist groups gain traction around the world and war crimes are still being committed long after the world proclaimed “Never Again.”

The Accountant of Auschwitz aims to shed some light on the question of responsibility and culpability at the root of all war crimes and how we might learn from the past to ensure a more peaceful future.

The Accountant of Auschwitz is opening this week at the Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema (506 Bloor St. W) on June 8. Following the evening screenings on June 8th & 14, there will be a Q+A with the director, producers and Holocaust Survivors. Get tickets here.

Ricki Gurwitz

Ricki Gurwitz is a former producer at CTV News Channel. She started her career in New York, where she was a producer at WABC News Talk Radio. She moved back to Toronto in 2009 where she took over the production of the The Bill Carroll Show and The Jerry Agar Show on Newstalk 1010. In 2011, Gurwitz made the switch to television, joining CTV News Channel as a segment and associate producer, working with reporters in the field to package news stories and in the newsroom to cover the headlines of the day. In 2015, Gurwitz left CTV to produce The Accountant of Auschwitz, her first feature documentary.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram