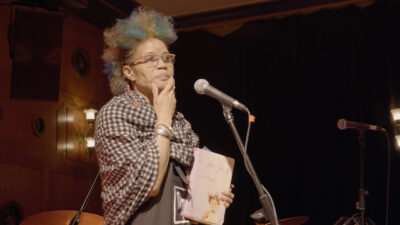

Staceyann Chin is a powerhouse poet, LGBTQ+ activist, and a gripping live performer. She proudly embodies many identities: poet, activist, lesbian, Jamaican American, mother. But this documentary chronicles her journey to unpack another one: daughter.

Staceyann was abandoned by her mother as a child, leaving deep wounds that carried into adulthood. In A Mother Apart, she travels the globe—following her mother’s trail from Brooklyn to Montreal to Cologne to Jamaica, seeking a bond with the woman who brought her into the world. At the same time, as the sole parent of nine-year-old Zuri, Staceyann grapples with how to be a mother when she never had an example of one.

Filled with poignant reflections on parenthood, forgiveness, and healing, A Mother Apart is an emotionally sweeping and contemplative watch that will have you reflecting on the role of mothering in your own life.

After its world premiere last month at Hot Docs Film Festival, A Mother Apart will now screen at Toronto’s Inside Out Film Festival on June 1. We asked filmmaker Laurie Townshend some questions about shaping this multi-generational story, her connection with Staceyann, her own thoughts on mothering, and more.

Can you tell us about how the documentary first took shape and why you decided to focus on Staceyann’s story?

Back around 2016, I was considering motherhood, and embarking on what would turn out to be 5 years of fertility treatments. At the same time, I was documenting – through photography – the Black Lives Matter movement in Toronto. I started to notice something that I hadn’t noticed before – mothers and their children at rallies, protests, community activations and marches.

It made me consider my own values and wonder what kind of a mother I would be if my fertility journey were to end with me having my own biological child. I continued to explore this theme of Black motherhood and decided to reach out to members of my community and beyond to develop a documentary treatment that focused on what it is to raise Black children in times of change and conflict.

Staceyann Chin was and still is a beloved spoken-word poet, writer, and performer who I had heard at a reading of her memoir in Toronto many years prior to approaching her. She also had a YouTube series called Living Room Protests that she did with her then 5-year-old daughter Zuri. I remember being so inspired by Staceyann’s style of parenting, and truly started to think of her as a model for the type of mom I wanted to be. Over the next four years, the development process took us from following a small group of mother-activists (of which Staceyann was a part) to honing in on Staceyann’s story, which suddenly developed some new urgency around her mother.

How did your connection with Staceyann evolve throughout the filming process?

My connection with Staceyann evolved organically over the course of making A Mother Apart. After a mutual friend introduced us via email, I took a Megabus to NYC during my March Break (I was a full-time middle school teacher at the time), and met Staceyann and Zuri face-to-face for the first time.

We immediately bonded over things like our shared queer identity, being Jamaican (even though for me it was through heritage and not birthplace), the act of mothering, feminism, literature and of course we talked a lot about our respective experiences of having a Jamaican mother. By the time production began, Staceyann and I had a mutual respect for each other and a deep trust that carried us through all the triumphs and challenges of telling such a personal story.

A Mother Apart spans 3 generations and takes us across the world—what went into deciding the structure of the story and which facets of Staceyann’s life to include?

Working out the structure of a story that spans so many countries and years was extremely challenging. For some time — especially in the first couple of years, I was traveling to Brooklyn, New York mostly to interview Staceyann and get to know her. But then one day she announced that after many years of declining offers to perform in Montreal (the city her mother fled to and where Staceyann always believed she’d live), she was going to accept an invitation from an arts festival there. We knew we had to follow her.

It turned out that during this Montreal shoot, Staceyann also felt ready to search for the house that her mother occupied when she emigrated from Jamaica. Her choice to finally say yes to the city that in many ways betrayed her (she took French lessons in Jamaica because she was convinced she would live there), felt like the beginning of a new way of navigating her painful past. The Montreal sequence does in fact land in the first 10 minutes of the film and goes far in setting the stage for what unfolds thereafter.

What was something you learned from Staceyann and her journey in the process of making A Mother Apart?

My biggest lesson came in our final interview with Staceyann when she made a statement so profound, we used it for the final voice over. I won’t give it away by directly quoting her, but the lesson I gleaned was that nurturing compassion for oneself is perhaps the most important thing to be able to do in one’s lifetime. I learned that grace for self begets grace for those who may have hurt you. It’s a teaching I think about every day.

How did this film shift how you feel about mothering?

Making this film has so profoundly expanded and deepened my definition of mothering. I don’t think I understood then what I know now—that to mother oneself requires a most radical love. In a world that is by design, full of obstacles, horrifying inequities, and violence disproportionally directed towards women of colour, it is a wonder to exist. It is a miracle to exist and to love oneself in the face of all of that. I learned that from watching the way Staceyann transformed the trauma of her abandonment—the way she confronted the belief that she must not have been worth staying for—to become the powerful, loving, provocative, and kind mother we see on the screen.

What was your approach to the visuals and overall look of the film?

Staceyann Chin, the award-winning spoken word poet, the activist, and feminist, is larger than life. Whenever she opens her mouth or puts pen to paper, she is boisterous, provocative, and fiery. This is the Staceyann the public knows. I wanted the film to visually echo that fire.

On the other hand, my editor Sonia Godding Togobo and I wanted the visuals to reflect the more vulnerable and tender aspects of Staceyann’s personality. In footage shot earlier in production, there is a lot of handheld camerawork. You almost feel Staceyann’s unsure footing as she walks around her mother’s old neighbourhood looking for any sign that she wanted her there with her. The use of colourful graphics to depict such difficult childhood realities also added a layer of tension that I know engendered empathy and connection in the audience.

What conversations do you hope the film inspires?

The conversations that I was invited into following the world premiere of A Mother Apart are the conversations I want to keep having. People young and old, cis-men, and women, trans people, gender non-conforming individuals, people from the Caribbean and everywhere else in the world were saying things like:

“I need to call my mother.”

“Even though I’m not a mother biologically, I mother many in different ways”

“I want to know more about who my parent was before they were a parent”

”What would it take for me to forgive someone who wounded me like that?”

”Who am I without this wound?”

”What do I have to say out loud that I’ve been keeping in”

”Who in my life can I extend more compassion towards?”

”How can I show myself more grace?”

When you look back on this project a decade or two from now, what do you think will be your most vivid memory?

Definitely the Hot Docs world premiere when we shared A Mother Apart with an audience for the very first time. It was a sold-out house, filled with old and new friends, dear family, members of so many different communities…the audience response to the film was overwhelmingly generous and sincere. I had people coming up to me unable to speak through their tears. Mothers identifying with Staceyann’s conviction to break the cycle of trauma passed down through generations. Daughters seeing their parents in a new light — feeling like they want to know more about who their parent was before having children.

That night in April, when we gathered to watch A Mother Apart, I called my late mother Laurel Yvonne Townshend into the room via a recording made the previous spring. In the audio that I held up to the microphone, my mom can be heard recounting a dream she had about a film of mine receiving accolades at ‘some big awards ceremony”. She goes on to say that everybody was looking at our family and congratulating us. “I was so proud to be your mother. My head grew!”. I still weep when I think about the fact that my mom couldn’t physically be at the premiere, but I know that she had the best seat in the house.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram