To tell sex worker stories, we need sex work decriminalized – but is that enough?

The global sex workers’ rights movement has done an excellent job of putting the full decriminalization of our labour at the forefront of our demands for equality and human rights. Organizations like Amnesty International, the World Health Organization, International Human Rights Watch, and UNAIDS, all support the full decriminalization of sex work as an essential starting point for reducing harm and tackling injustice around the world.

However, our ability to share stories openly and authentically without fear of discrimination and violence does not end when sex work is decriminalized. Black, Indigenous, and sex workers of colour, especially those who are queer, trans, and two-spirit, experience criminalization in a variety of ways beyond their sex worker status and will continue to face over-policing and under-protection by law enforcement long after sex work laws have changed.

The lives, labour, and bodies of sex workers have long tickled the civilian imagination. Popular depictions of sex workers – from whores with hearts of gold to the dead hookers of every true crime show – are fantasies that elude reality, because it’s never a sex worker telling the story.

In a Canadian context, sex workers are legally defined as victims. All of us. Victims, no questions asked. If we’re sex workers, we are assumed to have been forced into exploitation, with no autonomy to speak of. (Side note: name a single worker outside the sex industry who isn’t “forced” into “exploitation” – that is, labour under capitalism – with any “autonomy” to speak of? I’ll wait.) This legal framework is known popularly as the Nordic Model, a so-called “feminist” approach that seeks to “abolish” sex work by “ending demand” for our services by criminalizing our clientele.

While it is technically legal to provide a sexual service for money, it is criminal to talk to a client about boundaries, criminal to advertise one’s services, and criminal to pay a ‘third party’ for their services, be they drivers, security, or webmasters. As well, the wording of the ‘communication’ provision of Bill C-36 (or, the Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act) clearly targets street-based sex workers, who are disproportionately queer, trans, two-spirit, Black, Indigenous, sex workers of colour, who use drugs, experience houselessness, mental health issues, and disability, and have a pre-existing history with the criminal justice system.

The problem with the Nordic Model is that sex workers are human beings, not symbols, and these laws have tangible, harmful impacts on our lives. The Nordic Model has been widely shown to increase sex worker vulnerability to violence, and fundamentally relies on the criminal justice system to “abolish” sex work, ignoring the reality of who most often deals with the long arm of the law. In Canada, Black people make up 3.5% of the population, but account for 8.7% of the federal prison population. Indigenous women, who make up 4% of the population, now account for half the population in federal penitentiaries. Let there be no doubt who is getting disproportionately punished by these fundamentally racist laws.

So long as people need money to survive, there will exist people willing (and even wanting) to fuck for money.

It’s that simple.

Wanna solve the “problem” of prostitution? Abolish poverty. Racism. Transphobia and homophobia. Housing insecurity. Ableism. Discrimination in all its forms. Until I see that “anti-trafficking” energy focused on the inequalities that force people into the sex industry, I won’t believe it’s anything other than a morally corrupt cash grab.

After all, who benefits from our legal definition as victims? Certainly not us. Sure, technically speaking, it means accepting money for sex in Canada is not a crime, but with every other prostitution provision in the legal code, it is impossible to do sex work without breaking the law.

Personally, I find it victimizing to be labeled a victim. Being spoken for without my consent is victimizing. But without victims, saviors would have no one to save. Without victims, the funding for “anti-human trafficking” and “end-demand” organizations would dry up. Acknowledge our autonomy? They can’t afford it.

And frankly, a legal status of perpetual victimhood nearly guarantees future harm (and future funding!), because of the mounting evidence that the Nordic Model makes sex work more dangerous for sex workers. The law calls us victims but makes victims of us. A self-fulfilling prophecy.

We need more sex worker storytelling to change the narrative, but how can the onus be put on sex workers to risk their lives, reputations, relationships, employment, citizenship, housing, healthcare, and education, without a culture of safety and support?

Our stories contain unheard multitudes. Some of us, like me, have the social capital to risk the worst impacts of sex work stigma, but most of us will take our stories to the grave. White, cis-gendered sex workers have been culturally celebrated for telling their stories, while marginalized sex workers are routinely silenced, shamed, and shunned for sharing their experiences.

Sex work decriminalization is the least we can do to ensure a culture of safety around sex work storytelling, but it isn’t the end.

We must strive toward sex worker justice, with a goal of social transformation beyond the punishment system. Accessing justice is a fundamental human right, and no one should be excluded from legal protection because of their occupation. Accessing justice means eradicating the criminal laws that make it possible to arrest sex workers for reporting crimes perpetrated against them on the job. We must transform the way we deal with harm and accountability, with a goal of ending state and gender-based violence against people of colour. While sex work decriminalization would make storytelling safer for cis, white sex workers, sex worker justice would make storytelling safe for all of us.

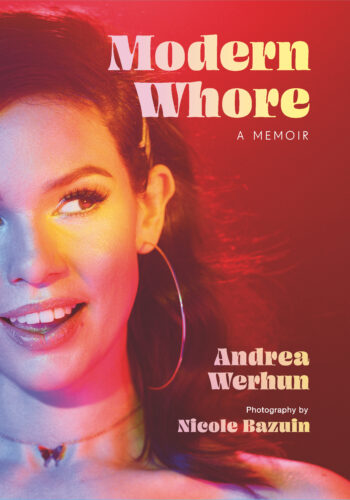

Andrea Werhun is the author of Modern Whore, a memoir documenting her career as a sex worker with striking photography from Nicole Bazuin. Werhun writes about her experience as a stripper, exploring the many identities of sex workers, the risks they take, and the rights our society is taking away from them.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram

We’re giving aw

We’re giving aw

Our Artist of the Month @ashleighrains spe

Our Artist of the Month @ashleighrains spe Where Carole King Leads, We Will Follow

Where Carole King Leads, We Will Follow