For decades, artist Shelley Niro has long been laying waste to lazily conceived and erroneous stereotypes about Indigenous women. Through her work, which often features her friends, family and herself as subjects, she calls us to explore our preconceptions of identity and culture, and she does so with a cheeky humour that engages as it challenges.

The 2017 Scotiabank Photography Award winner will be exhibiting her work at the Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival, kicking off this month.

We asked Niro about her process, her work, and what gives her hope.

SDTC: Can you walk us through your process (are you working on several works simultaneously)?

SN: I really try to concentrate on my work as it’s happening. I have a final concept in mind, but very often the look of it changes as I get towards the end. If I make the work the way I start out seeing it, then there’s really no point in making it. It’s always a surprise to see how far you can go with making stuff, but the concept will always be the same.

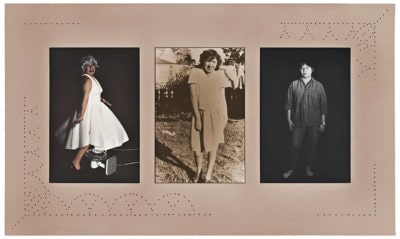

Shelley Niro, Five Hundred Year Itch, 1992, from the series This Land is Mime Land. Gelatin silver prints with applied paint; hand-drilled mat. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Gift of Sandra Jackson, Bramalea, Ontario, 1995

What are you working on now?

Right now I’m working on a feature film, and that takes up all the time. It’s called The Incredible 25th Year of Mitzi Bearclaw. It’s about a young Native woman living in Toronto. She has a desire to become a hat designer, but then she gets a letter from her father asking her to come home and help look after her mother. They live on this island up north, alienated and isolated from the rest of the world. The mother is a residential school survivor, so she is not one of the most pleasant people to be around. And reluctantly, Mitzi Bearclaw goes home.

It’s meant to be a comedy, so there are hilarious moments in the script. It also touches on the environment and how it affects Native reserves in northern communities. There’s talk about water, the environment, even the animals that live up there and how they’re no longer around.

Why did you want to create this film?

Being aware of what’s out there based on Native realities–and seeing what’s also being shown of Native situations in film–there’s always a certain kind of feel to them. Alcoholism, suicide, poverty–all those things seem to be involved in the storytelling. I just wanted to do something that didn’t have to focus on those kinds of elements in the story. I was really trying to make a comedy.

There are so many films I like in this genre. I like Jim Carrey and how he avails himself to be as crazy as can be. It’s almost like unapologetically letting himself go as far as he can. I try to look for those kinds of influences, see what works, and see what speaks to me.

How has your work evolved over the last few years?

My work has gotten bigger in size. But I produce less because frames cost more, so it isn’t very practical [laughs]. I’m not producing as much as I’d like to; I’ve become more of an administrator of my own work, and that takes up a lot of time and energy.

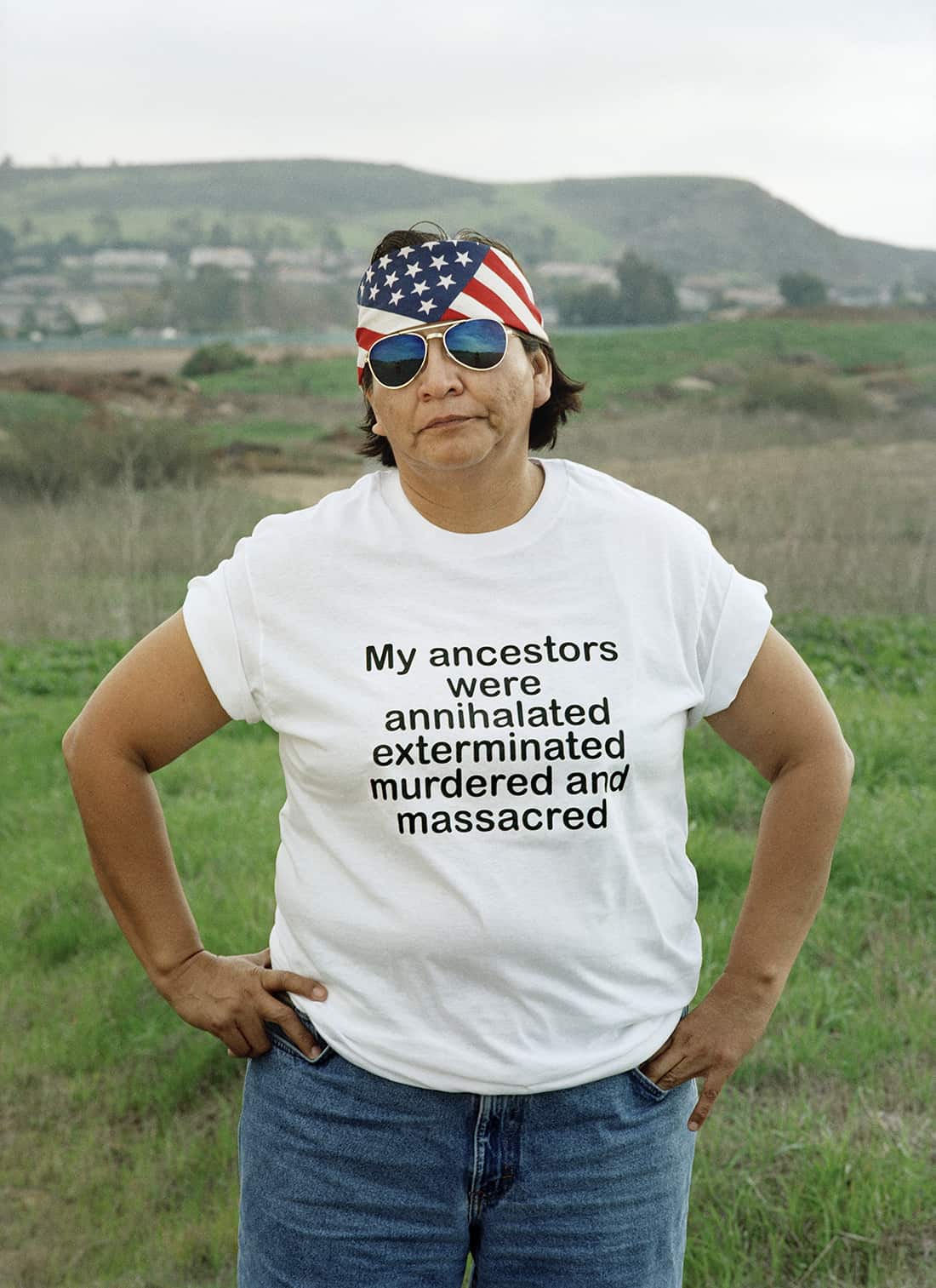

Shelley Niro, The Rebel,

1982–1987, gelatin silver print with

applied paint. Courtesy of the artist

In the past, you’ve focused on primarily Indigenous women. Why is that?

I really focused on the Indigenous female portrait. [Past representations] have been not real. People only want a certain kind of image. Well, those are nice, but these are real Indian women. These are what we look like. I think it’s so important, especially in the light of missing and murdered women, to show a positive image of Native women. We are productive; we are contributing to Canada. I think people get the overall impression that Native people don’t contribute to Canada–that we’re just taking away from it.

And you’ve interspersed yourself in the images.

Sometimes you can’t get a model. You know you want to do the work, so you just put yourself in front of the camera. I think it’s a good exercise because you’re sort of abandoning everything when you use yourself as a model. Some people might say, “Oh, you’re so conceited.” I don’t thinks so! It’s not only economical; you’re also telling your own message.

Shelley Niro, Flying Woman

#5, 1994, gelatin silver print.

Courtesy of the artist

What’s the significance of the flying woman image?

The flying woman series is loosely based on “Sky Woman,” the creation story from Haudenosaunee culture. I just like the ability of this woman to fly. I started working on that photo series in 1994. It was really freeing just putting her in a position where it looks like she’s flying.

What should we be paying more attention to?

Indigenous people. It seems to come in waves: “We’re going to pay more attention to Indigenous people this year, and we’re going to include them in more things.” You get a little skeptical about that sort of thing because you think, well, will next year will you be paying this much attention? For me, it’s just like, what’s the big deal? Just include us. Include us in everything.

Do you think reconciliation is possible?

Reconciliation is not possible until they start improving education on reserves and make an effort to get clean water there. Let’s start with the basics. I think education is low grade on their scale, and until it becomes a priority, I don’t think anything will really change.

What gives you hope?

I look at Native writers, artists and musicians–everybody is working their asses off, trying to make that voice heard. That gives me hope.

What do you hope people take away from your exhibition at CONTACT?

The curator wanted to concentrate on portraits in my work. Some of them are self-portraits. There’s work that goes back to the 1980s. It’s a bevy of images. You want to make an impression, showing that a lot of care and love went into making the work. And hopefully it resounds off the walls.

Scotiabank Photography Award: Shelley Niro is one of the primary exhibitions of the Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival, on view from April 28 to August 5, 2018. The exhibitions will be launched at the official kick-off party on April 27, 2018, 7:00–11:00 p.m. at Ryerson Image Centre (33 Gould Street). Find more information here.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram