Writing has anchored me during some of the most challenging times of my life — including times where there were threats to my psychological and physical safety.

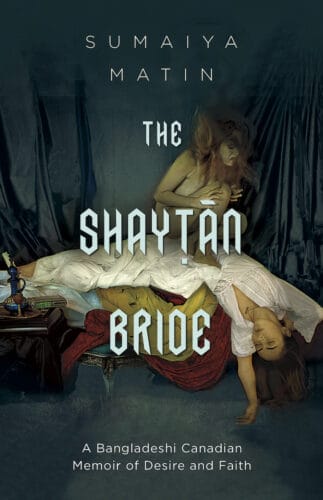

In my debut coming-of-age literary memoir, The Shaytan Bride: A Bangladeshi Canadian Memoir of Desire and Faith, I write about my experience escaping an attempted forced marriage in a state of traumatic shock.

At the age of nineteen, I found myself under house arrest at my uncle’s home in Dhaka, Bangladesh for almost half a year, without access to communication with the outside world, or my Canadian passport. To leave, I had to agree to a proposed marriage.

During this time, it took every ounce of will to exercise my voice and continue saying no. My fundamental trust had been broken — not only in those I deeply cared about, but also, the world at large.

Forced marriage is different from an arranged marriage. In an arranged marriage, candidates for marriage may be presented as options by friends and family, but the two people involved would provide their consent. In a forced marriage, one or both parties do not consent to the marriage.

A forced marriage can happen at the snap of a finger without one’s knowledge, and in other cases, be a gradual process involving varying levels of coercion, threats, and isolation. With the loss of identity markers over time, of not being heard and being physically confined, a sense of learned helplessness can form, leaving one feeling a lack of agency within one’s circumstances or overall life. The impacts are significant on one’s mental health, as is most trauma, including a loss of perceived and actual safety, and depression, among others. Staying in a forced marriage increases the likelihood of experiencing domestic violence, but leaving one can also be risky, especially with a lack of access to supports.

The prevalence of forced marriage remains high worldwide. It is not limited to any particular culture, religion or community.

My own experience of attempted forced marriage happened in the summer of 2005 in Dhaka. For the entire five months I was there, I wrote in a moleskin journal in secret, penning recollections of my previous life, and anything really, that would create more cohesion in my sense of self which was fragmenting over time.

It was summer. In Toronto, the city would be alive. The streets

would be full of people, not looking down or away, as they usually

do on winter evenings, but instead looking at each other,

soaking up the calm, joyous, ever-present expressions on one

another’s faces. They’d be sitting on patios, raising their glasses

for no reason at all, or trying on vintage clothing in Kensington

Market. People on subways and side streets, in front of bright

murals, playing tunes on various instruments in a type of vagabond

fashion. There would have been all sorts of festivals lined up:

Caribana, Pride, Jazz, Afro-Carib, Summerlicious, Cider, just to

name a few. There would be wild bergamot and meadow rues in

High Park, and ferries doing daily rounds at Harbourfront. People

would still be humming to Nelly Furtado’s “I’m Like a Bird” or

talking about the last season of Sex and the City or digesting the

newly aired Grey’s Anatomy. The sun would be bright — yes, it would be bright.

Bright for Canada, at least.

But I was in Dhaka, Bangladesh, sitting in a room full of darkness, in a city where sunlight is a constant.

It was almost a month into the trip, and I was now under house arrest.

As I wrote, I started to give the chaos I was experiencing a beginning, middle, and end. I penned the whispers of my heart, the thoughts that intruded my mind, the recollections of sensations that came and went, leaving imprints on my skin. In my traumatic shock state, I observed myself. There were words I wrote between other words I wrote, that reflected back to me who I truly was, when the world around me could not.

Women throughout history have had what they know, their truths, doubted and misconstrued. Carol Gilligan, an American psychologist and ethicist, contends that from a very early age, young girls are taught through socialization, to suppress open expression of their true voice in order to be obedient. They are taught to focus on the experiences of others, to value relationships and base their sense of morality on them. In this process, I believe young girls learn that they should trust others first, instead of being encouraged to trust themselves. At the systemic level, if women do express their truths, they are subject to a range of repercussions. Time and time again, we’ve seen women lose credibility, jobs, families, basic respect or a sense of safety for living their truths.

In The Shaytan Bride, I share historical and present-day examples in postcolonial South Asia and neocolonial North America of how women’s bodies became platforms for others, specifically men and others in power, to express political agendas or ideologies, or were collateral damage in times of war and conflict. Entire societies are organized around shame of women’s bodies and the meanings projected onto them, meanings that have nothing to do with the intimate knowledges and experiences of women themselves.

As a nineteen-year-old, while I continued to make sense of womanhood, the latent and overt messages about who women are and how they should be, in all of my cultural frames of reference, including North American, never seemed to truly resonate with my soul. In the noise of these various narratives, I wondered, how can I truly listen to myself?

In Dhaka and after, my emotions were delimited and it felt as if my physical body could not hold them. When I wrote, however, the blank page was an ever-expanding container. It gave me permission to traverse the layers of my individual experience to reach collective intangibilities, and to reflect on, question and negotiate them. Somehow existence could be organized again, somehow what I knew could resurface again, despite the doubt and confusion that plagued me about what I needed to do, and how.

Writing helped me to choose — out of my own agency and will — to accept the hand extended to me by the Canadian consulate — and remove myself from the situation I was in.

It was by holding onto that shard of writing, that helped me understand what was happening. Through documenting my feelings, I was able to access myself, and save myself.

Stories can be used for oppression or resistance. In the act of sharing my very private pain in such a public way, I am sharing the art that is my life, with others. I know there are many other women, people, that may have experienced a vulnerable moment in their lives, where maybe their truth was snatched from them, institutionally, by the media, by the people they love, even by themselves.

We are linked in this experience, for as storytelling creatures we are prone to lose and find ourselves in stories — for good or bad. As we find the commonalities in our experiences, we can engage with our human pain differently — if we choose to make sense of our suffering, together.

What anchored me in Dhaka and continues to now, is my inner knowing that emerges from time to time in what I create, how I express myself. My writing, my art, reflects back to me what I need to see at any particular time. What I see can change, because I am constantly changing too. Art is permeability, elasticity, movement, expansion — when the world tries to bind us in some way. Our power is in our expression; that, no one can take away.

Sumaiya Matin is an advisor/consultant, social worker/psychotherapist, and writer living in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. She is the author of the literary memoir, The Shaytan Bride: A Bangladeshi Canadian Memoir of Desire and Faith, published by Dundurn Press in 2021. Instagram: @sumaiya.matin | Twitter: @sumaiya_matin |www.sumaiyamatin.com

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram