Up until a few years ago, I didn’t think that being Asian was something that belonged to me. The cartoons about a monkey with superpowers or talking cats; rice served for breakfast, lunch, and dinner; Chinese school on Saturday mornings; trying a new food or herbal concoction every week because a friend’s email told my mother it promoted brain health—none of these, I felt, were experiences that gave me the right to identify as Asian.

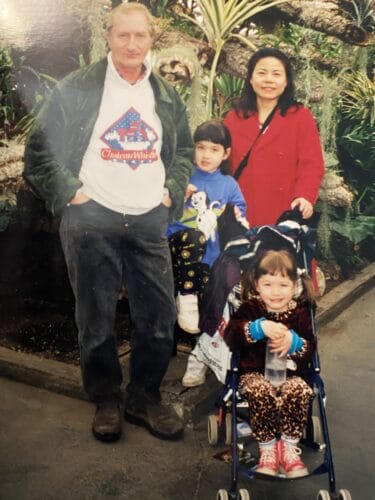

For many mixed race East Asians, especially those who are part white, biracial is a state of in-between. For me, building a solid foundation on which to describe my identity has been more challenging, since fundamental self-attributes like race and ethnicity have gotten jumbled up through my multiracial experiences.

The many “No way, I would never have guessed!” and “I can kind of see it now that you’ve told me” comments made me even more confused about whether I even belonged to the Asian identity. The perception of others would fuel my budding racial impostor syndrome: how could I see myself as Asian, or even biracial, if other people didn’t even believe I was? Ultimately, out of a naive understanding that that’s what I was “supposed” to do, I fell into the unspoken social pressure to pick the white side of my background to determine who I was.

Identity issues are a common struggle for mixed-race individuals: a 2015 Pew Research Center report on being multiracial in America found that around 6 in ten multiracial individuals don’t identify as such. However, I’ve seen this struggle especially affect younger people, whose most significant development is figuring out their identity, while also still holding onto a need to fit in socially. The same Pew Research report highlights that 46 per cent of multiracial Americans are under the age of 18, even though this age group represents just under a quarter of the country’s population.

When I was younger, I watched a CollegeHumor sketch titled “Are You Asian Enough?”, in which a man who is one-eighth Korean stands before a tribunal to determine if he is Asian enough to do certain things like brag about his grandmother’s Korean food or do a broken English accent as a joke.

Although this was just a short comedic video, it often does feel like being multiracial is like being put on trial. From my white peers, I would commonly be asked to “say something in Chinese”, as if I somehow needed to provide evidence that would satisfy their standards of what makes someone Asian.

But on my Asian side as well, I couldn’t help but notice a sort of disbelief that I was part of the same community. Not only is it difficult to understand my East Asian friends’ lived experiences, my family’s standards for me actively cultivating my Taiwanese identity also seem much lower.

For example, my Asian-Canadian friends whose knowledge of Mandarin was as basic as mine would get scolded by their relatives when they went to visit China because they ought to be more in touch with their Chinese roots. But on the other hand, the three grammatically incorrect sentences I was able to utter during a family dinner in Taiwan would evoke impressed reactions around the table. In the same way a foreigner isn’t expected to be fully integrated within a new culture, my sister and I weren’t considered to be responsible for integrating Taiwanese culture into our lives.

Canada’s representation of multiracial identity, whether in the media or in national data, is extremely behind despite mixed unions almost doubling between the early 1990s and the early 2010s. Although mixed race individuals only made up around 3 per cent of the total visible minority population of Canada in 2016, this number is over 2.5 times what it was in 1996. Comparing this number to the country’s general population growth of just over 0.25 times in the same time frame, it’s important to open conversations about and normalize multiracial Canadian identity.

It’s equally important to consider that being multiracial isn’t a sacrifice or a compromise between clashing identities, but rather a balance. Encouraging people to be proud of their non-white heritage is quite a widespread narrative now, but it can come at the expense of our white background as well. In the end, rejecting white culture in the name of racial self-acceptance is still a harmful mentality to adopt.

The concept of Asian Heritage Month as a pan-Asian celebration also seems somewhat idealistic—after all, it is a huge, diverse continent that can’t be summed up into a single identity. But part of its importance comes from its ability to acknowledge and validate experiences that specifically pertain to Asian people who live in a North American context.

It is common for Chinese households to leave little room to express strong emotions and topics like mental health, which are much more openly discussed in Western society. As a teenager, I would wonder why our home was void of “I love you”, while my white friends would express their affection for their parents constantly. Instead, I would get a plate of cut fruit or a freshly squeezed glass of orange juice, a gesture I only later understood to be a significant way for Chinese parents to show care.

In a similar way, though my mother tried to teach us about our culture, identity was an absent theme in our conversations. I grew up in a society where most people embrace the single race they belong to. But realizing that this wasn’t an experience that applied to me, and therefore that I didn’t need to try to relate to it, allowed me to be more open and curious about my background rather than to feel guilty and uneasy about how I defined each identity. In the same way I learned my mom’s love language, I also ended up celebrating both parts of my heritage and finding ways to bridge the gap between them.

Elyette Levy is a 22-year-old freelance writer based in Montreal (Tiohtià:ke). You can find more of her work about biracial identity, Asian representation, and digital culture at elyettelevy.com or on Twitter, @ElyetteLevy.

This story was selected as part of Shedoesthecity’s New Voices Fund, established to help continue offering opportunities to talented emerging writers with less than 20 bylines. More info here.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram