My dad has kept so much of my mother’s paraphernalia, it threatens to burst out of boxes and closets, re-opening the door to a sadness for all of us that has never dulled. I’ve learned to approach those items with care, knowing that I can both activate, and drown in, my mother’s presence through the tangibility of her items — the last handbag she carried, still containing receipts and pennies. Her handwriting in a card, sent to her cousin and returned to us years later, sharing how active I was becoming as a toddler. Albums of photos, grainy behind crackling cellophane, falling out of their positions with each ginger viewing.

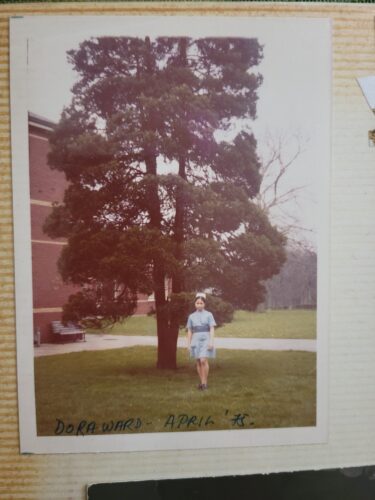

In August 2021, I responded to a call for stories of nurses who had worked for the NHS — Britain’s National Health Service — which had been a pipeline in the 1970’s and 80’s for health professionals from Asia to settle abroad. My mother was one of them, a fresh-faced 21-year-old from the Philippines. No WhatsApp or Facebook to connect easily with family back home; bridging the distance with letters and supporting her parents and siblings with her meager student-nurse wages.

Through this archival project, part of British East and Southeast Asian Heritage Month, I was so grateful to be given a platform for my mother’s story — a chance to honour her, feel close to her, and celebrate her. The opportunity felt more significant still, because of the timing: I had just brought my baby girl, my mom’s first grandchild, into the world. One that she’d never get to meet, as we lost my mom to cancer in 1995. I was the awkward age of 11, my sister 7, and my dad left to navigate the upbringing of two motherless daughters, let alone his own grief.

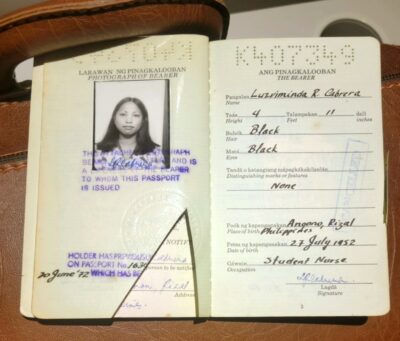

I was also grateful for my dad’s borderline hoarding — I knew I’d have lots of treasures to share for the heritage exhibit. In one bulging leather bag, I snapped pictures of my mom’s old passport, her nursing certificates, even her ID badge for the hospital where she’d worked. I was struck by the sensory richness of the moment: there I stood, my weeks-old daughter wrapped to my body, sleeping. The pressure of her, the scent and softness of her hair — all so visceral and immediate. Equally so was the texture, the lightness of the papers unfolding in my hands, some 50 years old. The line connecting us through 3 generations felt tangible, one hand on my baby and one smoothing the pages of my mom’s old notes.

My mom, though she started her career as a psychiatric nurse, enrolled in further training to become a midwife. Throughout my pregnancy, I felt a longing for her guidance. I found myself not just wondering about the child I’d bring into the world, but also the child I’d been; how I’d changed my own mother’s life by bursting on the scene.

My birth story has long coloured my sense of self, and my impression of my mother’s love for me. It was a difficult labour, attended by my mom’s own nurse-midwife colleagues, resulting in a C-Section that my father says saved us both. My secret fear has always been that this C-section (and by extension, my arrival) disappointed my mom. Years later, a therapist would help me unravel this conviction; the fear that I’d been too big, too much, too traumatic for my mom. It was plain to see how much she loved me, but in my child’s mind, the only explanation I could grasp for why she was no longer with us was that I’d been bad in some way.

During my pregnancy, I railed against the idea of a C-section, hoping to avoid facing a similar birthing story. As my due date passed, and the midwife team started discussing labour induction with me, I insisted on waiting another week… 2 more days… 1 more day … until finally I was 2 weeks late with no signs of labour. In the end I found myself on the operating table, reckoning with the reality of my 9 lb babe and ready to meet her after nearly 10 months of pregnancy.

And there she was. My baby. Not too big, not too anything — except too beautiful for words. My heart, beating outside my body. At my most emotionally and physically vulnerable, I couldn’t help but feel my mother’s presence with me in the hospital. I felt the circularity of our birth stories. The C-section was the birth I needed to have, to face the wounds I’d buried deep about being left behind, and the stories I’d told myself about not being worthy of a mother’s love.

Taking part in BESEA Heritage month, documenting my mom’s nursing and midwifing journey, felt like a ritual; part of my becoming. It allowed me to learn about the woman my mother was, and recognize myself in her. Until I opened that dusty leather bag, I didn’t know that my mother had bought her family’s plot of land from the city and gifted it to my grandmother. I didn’t know that she’d studied at the top university in the Philippines on a scholarship, before deciding to change course and move to England to earn money to send home. I didn’t know that she’d delivered over 1000 babies, proudly handing them to their mothers in her crisp blue uniform and cap.

The making of a mother is shaped by those who mother her as she learns to mother hers. My mom was a part of that for so many. I leaned into these moments of loving care and connection. The labour nurse, who stroked my hand as I pushed in futility for hours before the C-section. My stepmother’s hand on my back as I breastfed through tears. I firmly believe that “mother” is not a term forged in biological connections, but emotional ones. I’m lucky to have the love and support of many seasoned mothers: my stepmom, friends, and aunties.

Still, learning about my maternal lineage felt important to my transition into motherhood. It’s allowed me to see how I am leaving an indelible mark on my babe the way my mom has on me. The legacy of mother loss is that I have a real fear of dying and leaving my child too soon. I wonder if she’ll know the story of my life, the person I am that’s been changed by her.

What I do know is that, though my time with my mother was short, it is etched in me. I know firsthand that her love made me who I am, more than her loss ever did. This knowledge permeates the challenging times and sleepless nights, giving me grace when I feel (as all mothers feel) like I’m failing at everything I do. I remind myself that I may not be given as many days to mother as I wish, so let me imprint my love for her in every moment she experiences. Let her know in her bones, in the memory of her cells; in pictures, letters, archives and stories; that I am her mother and she’ll always be loved.

Thanya Duvage is a 38-year-old new mother, of Filipina and Sri Lankan descent. She lives in Toronto with her Australian partner, and her child who will have more flags sewn on her backpack than there will be space for. She works as a speech-language pathologist in the disability sector, and has trained as a yoga instructor, using both backgrounds in the service of birthing accessible and decolonized worlds.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram