The mother-daughter relationship is fraught with complications – and the guilt goes both ways. We’re damned for the choices we make, and not making a choice is simply not an option.

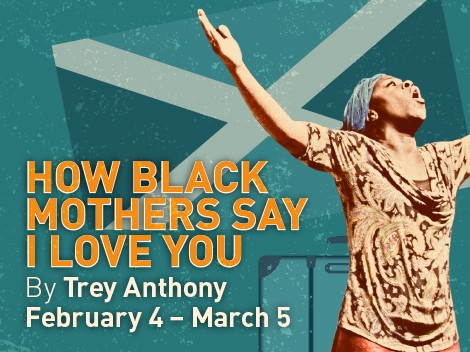

Trey Anthony’s play, How Black Mothers Say I Love You, is a poignant (and frequently hilarious) examination of the desire for truth and understanding after mothers are seemingly left with no choice but to leave their children and seek better lives for their families abroad.

We spoke with Anthony about coming to grips with our imperfect mothers, regrets and forgiveness.

SDTC: To what degree is this play lifted from your own experience?

TA: The play deals with the issue of a mother leaving the Caribbean and coming to Canada and being separated from her children for six years. This is something that happened in my own family. My grandmother left my mother behind for six years in Jamaica. Then when my mother came to Canada, she left me in England with my grandmother for four years.

Also there’s the whole issue of Daphne – the main character – who is very religious. She’s dealing with the separation from her kids but also her daughter coming out to her as queer. This also happened in my own family – with my own mom dealing (or not dealing with) my sexuality.

How did the women in your family react to the play?

I was reading the book The Five Regrets of the Dying. I had gone over to see my grandmother. At that time we knew she was terminally ill with cancer. I had my iPhone out and I said to her, “Grandmother, what’s one of your biggest regrets?” I thought she would talk about not going to school or getting an education. Without missing a beat she said, “My biggest regret was leaving my children behind in Jamaica, especially your mom. She never forgave me for that.”

My grandmother was a very stoic woman and never really expressed emotions. She started crying. When I told my mother this, my mother didn’t even believe it. I showed her that video, and my mother got very emotional. My grandmother unfortunately passed before we did the first reading of the play. My mother came to the first reading and was crying in the front row. She also came out to opening night last year and just loved the piece. I think it was a healing piece for her to see.

Did it change your perspective toward your mom and grandma?

It was really about examining choices and motherhood. I think before, my own response to my mother was to judge her very harshly. What she could have done, what she should have done. As a mother, I would have hoped you had done this, and you didn’t. But as I started to do the play and did more research on who my grandmother was and her childhood, and then also talking to my mother about her own childhood, it made me come to a place of forgiveness. As women, we suffer from that. We have this ideal of who we want our mothers to be, instead of looking at the fact that they are very fractured and fragmented human beings. A lot of them came from less than ideal situations themselves, yet we expect them to mother in a way that they become these superheroes, or women who can do no wrong.

It was really healing to see my mother not just as my mother but as a human being, someone who made choices that maybe I didn’t agree with, but she really didn’t have much choice in that. So she made the best choices that she could. It got us speaking as a family, and we had never spoken about these things before. I don’t know if it was because it was such a quick timeline – because we knew that my grandmother only had three months to live. For the first time, she really wanted to talk about the decision and what was behind leaving her children. I felt she needed to get that out. It was kind of a purging for her.

What was the biggest challenge you faced with this production?

Getting it produced. Going to theatre companies here in Toronto and saying, “I want to do a story about a Black woman who leaves her children behind in the Caribbean.” It just did not go over well, they thought it was too niche. They didn’t think it was a story people could relate to.

Out of necessity, because I knew the story was so important, I produced it myself. What I was shocked at was how people of all cultures and all genders related. At the heart of it was a story about a mother who wanted to gain love and acceptance from her daughter. And it was a daughter who didn’t think her mother did a great job. I think that crosses over race, nationality and gender.

People can relate to dysfunction. All of us have some level of dysfunction in our family. I was really shocked at how many people outside of the Caribbean community were just like, “That is so my mother.” I remember taking an Uber one day after rehearsal. The driver was Romanian. I said I was coming from the theatre and told him what I was working on. He said, “Well, I left my son behind in Romania for seven years and then I sent for him. Our relationship has never recovered. He’s always been really close to his mother, and he hates me for leaving him behind.”

When I told my Jewish friends the title was How Black Mothers Say I Love You and that I grew up in a household where my mom didn’t say I love you, they said, “That’s a very Jewish thing too.” I found out how people really related to the story and took from the story what they needed to take.

What’s been the most rewarding aspect?

How transformative the piece has been for so many mothers and daughters. When women are able to see it and say, wow, I never looked at it that way. Or, I was able to forgive my mother or have conversations with my mother I’ve never had – that has been the most rewarding for me.

Also, for someone like me who is a Black actor and writer in Toronto, to be able to be give an opportunity for actors of colour to have a really great piece to work with and good characters – those opportunities don’t come along enough. To be able to cast everyday women and have women of color really taking up center stage – that’s been rewarding for me to give those opportunities. Also, for young Black women in the audience, to be able to finally see themselves reflected authentically onstage.

And also, proving people wrong. That there WAS an audience for this. That has been rewarding – to see the audience respond in such a strong way at the box office. It made me know that I was really onto something.

Any advice to other young female playwrights trying to get their stuff out there?

I know for myself, even after the success of ‘da Kink in my Hair, I was under the impression that I would be able to go to any theatre company and get this piece in the season. And that wasn’t the case. Out of necessity, I self-produced the work.

If you believe that your work is important, and you believe in what you do, find a way. There are never going to be ideal circumstances to do your work. But you must start. I think a lot of times we wait for permission or for someone to grant access or give us funding or say, “Okay, do this, I like you.”

Sometimes you just need to like yourself enough to believe in yourself. You have to have a level of tenacity and a certain level of arrogance to believe it is good. No one is ever going to see your work if it’s in a drawer in your desk. Even if it means putting it on for one night and inviting the hell out of people to come; then do it.

How Black Mothers Say I Love You returns to Factory Theatre (125 Bathurst) February 4 through March 5th. Get your tickets here.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram