Codependency has always been an idea that I’ve struggled to understand, but a friend recently gave a good analogy: “It’s when there are no hard lines or edges. When two lives are blurred into one.” Instead of clear boundaries, there are frayed ends. The lines that typically delineate distinct roles spill out, bleeding into one another, making it nearly impossible to distinguish their point of origin.

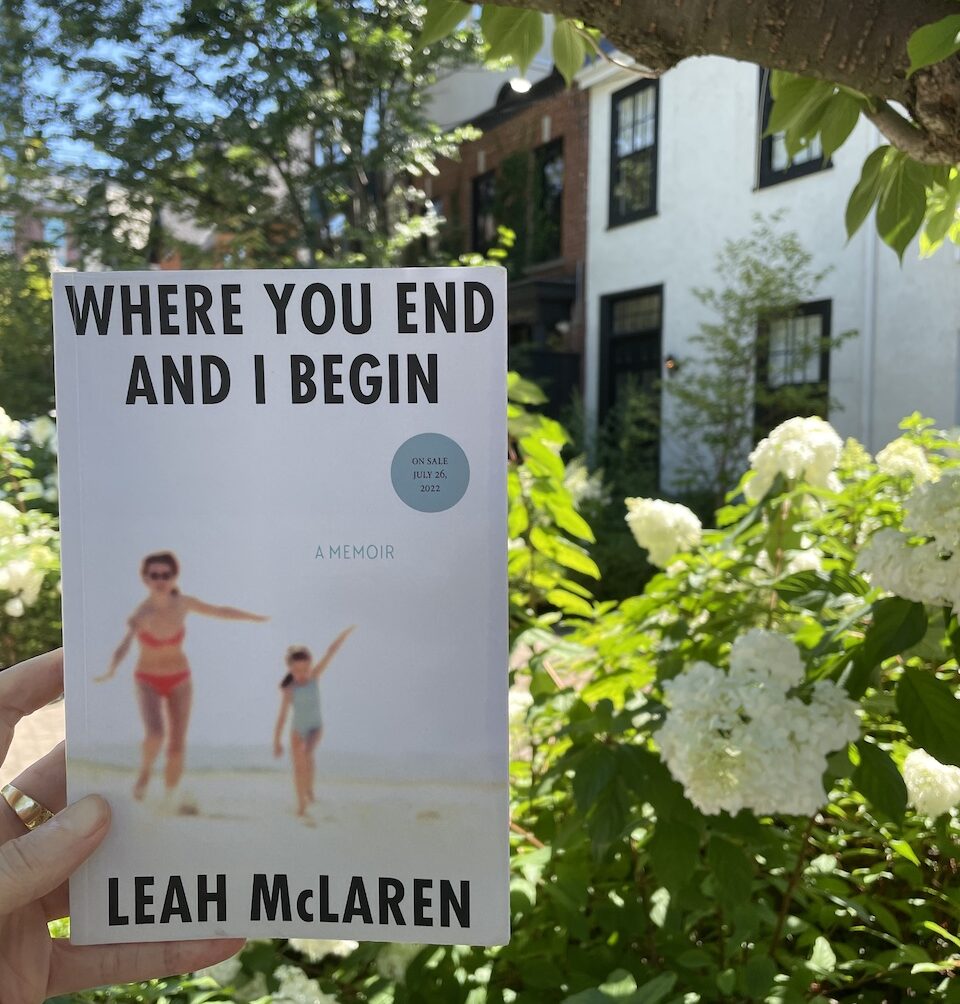

The subject of codependency came up while we were walking and talking about Leah McLaren’s controversial page-turning memoir, Where You End And I Begin (controversial because Leah’s mother, writer Cecily Ross, has publicly stated that she’s not okay with the book). However, Leah’s relationship with Cecily is less of a codependent one, and more of a messy enmeshment (something Leah’s written about extensively), but regardless of the term used in therapy, anyone who has experienced a relationship with blurred lines and a lack of boundaries will strongly relate.

“When I say there were no rules, people often think ‘oh, she was a party mom’ but it wasn’t like that,” says Leah. “We were best friends and I became a 35-year-old when I was 15. We read the New Yorker together and hung out and it was all very cool and Gilmore Girls Toronto.” It’s a fun picture, but also just one side of the story.

In the early 1990s, the two of them lived in an apartment on Beverley Street, in Toronto’s downtown Chinatown neighbourhood. Leah had no curfew, and no real bedroom wall. Meals weren’t regularly prepared or enjoyed at a table; Leah would often eat on her own (or not eat—during phases of disordered eating), for days at a time, when her mom left… without any real indication of when she’d return. When Cecily’s lover (who creepily lived in view of their back window) rejected her, which was a regular dramatic ordeal, Leah would stay up late to comfort her mom, the two gazing into his home, sometimes watching while he wooed another woman. When a pervert started to visit Leah’s basement window, hoping to catch her undressing, her mom didn’t take it too seriously. Her unusual upbringing lacked key elements of caregiving, but Leah wouldn’t change a thing.

“The things that fuck you up—they also are you. I would not change a moment, a minute, a second of my childhood because my mom, and our deeply enmeshed relationship, was very joyful and loving. There are children who know they are loved and children who don’t. I definitely and happily fell into the first category.” You can feel loved, be loved, and also experience trauma.

In a “normal” parent-child relationship, the parent looks after a child, protects them and nurtures them. The parent is the adult, and the child is the child. But in her memoir, Leah paints a different picture. Her mom is not a bad person—and Leah doesn’t describe her that way—but she’s an imperfect human, like the rest of us, who has made some questionable choices. Where You End And I Begin is not about blame, but accountability, and looking back to make sense of the present.

Certain chapters outline neglect, while others describe a strong bond, a magical childhood, and exciting teenage years—life can be all these things at once. “The biggest thing my mom gave me was such confidence and intellectual confidence in my voice, in my writing. It was such an edge for me in the beginning of my career because I was so unintimidated by other journalists.” It was during these early years as a newspaper columnist when the cracks began to show, when Leah began to understand that her childhood was different, that her mother was not like most moms.

In a piece for Chatelaine titled Give Me My Life Back, published in 2007, Cecily laid bare her true feelings about having Leah and her sister. Reading this in print, and without any warning, was both shocking and hurtful for Leah. Although upsetting, it wasn’t out of character—her mom reminded Leah frequently that writers write. But there are consequences.

“I thought of childhood and adolescence as this wonderful thing and my mother as this wonderful person but I had to acknowledge that it wasn’t quite that simple of a story.” The piece in Chatelaine helped make that clear, but it was when Leah became a mom that she really noticed that the concept of ‘mothering’ was largely unknown. “When I had children of my own, I really started to crumble and fall apart. My templates were so messed up, in terms of how to be a nurturer because I basically had never been nurtured.”

In our knee-jerk society, people who haven’t read the book—or even one chapter—will be quick to judge Leah for sharing her mother’s childhood trauma. But parts of Cecily’s story are also parts of Leah’s, they bleed into one another, and to understand that, you really must read the book.

“We’re a family of writers, we answer each other in print. But I also reject the idea of trauma appropriation or story appropriation, I think it’s a really dangerous idea,” says Leah, who’s no stranger to criticism. “People have said to me straight up ‘What kind of daughter would write about her mother without her mother’s consent?!’ My answer is a daughter who was mothered by my mother. When you break all the rules, which my mother did, in terms of what is allowable and permissible and taboo, in the parent-child relationship, I feel like that is my permission.”

Biking down Beverley Street, Leah comes to mind again, but this time I’m alone. As I breeze past a row of apartments, I think of her at age 15, dancing ecstatically with her mom on New Year’s Eve, with a dozen adults looking on. Her book describes the best of times, and the worst of times.

Although different from my own life, there are many parts of Leah’s story that resonate, especially having grown up in Toronto in the 1990s with divorced parents. But all women will find slivers of their story in Where You End And I Begin because we all have complicated relationships with our mothers. No matter how healthy or loving things may be, mothers and daughters have tricky tensions that are difficult to pinpoint, to describe. Most don’t dare to dig into those messy grey areas, they’re ever so tender and prone to eruption, but Leah digs. She digs ferociously into the “don’t go there” zones, and in her daring pursuit to make sense of a messy childhood, she passes back a flashlight, encouraging others to do the same. But be warned: excavating comes with risk.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram