Documetary Filmmaker

by Jen McNeely

Jennifer Baichwal’s films shed light to the corners of the world that we may otherwise never know. The subject matter she chooses to document offers us valuable insight, new perspectives and forces us to think about difficult and uncomfortable issues that undoubtedly prompt tough ethical and environmental questions. Perhaps most importantly, her work shines a spotlight on our own behaviour and forces us to carefully examine our actions and values.

Although she has accomplished several films, the two notable being; The True Meaning of Pictures: Shelby Lee Adams’ Appalachia and Manufactured Landscapes. To say these films will move you would be an understatement. If you haven’t been privy to Jennifer Baichwal’s films; expect to be shaken to the core.

Shelby Lee Adams is one of America’s most controversial contemporary photographers. He grew up in the Appalachian mountains of Kentucky, and focuses his work on capturing the poverty that exists amongst small remote communities and families that live there. He is often accused of stereotyping his subjects as incestual and backwards.

The film examines the questions that swirl around objectivity and the role and responsibility of a documentary photographer. Baichwal captures the points of view from both the families being photographed as well as anthropologists, revered art critics and gallery owners in the high brow art and media world. It is a haunting, revealing and endearing film that will linger in your mind for a long time. .

To tackle this issue with the medium of film and in the form of a documentary filmmaker, is a complicated challenge and raises much debate amongst general audiences and communication theorists alike. I asked Baichwal what her stance was on the role of a documentary filmmaker ensuring objectivity, and she bluntly answered, “That’s bull shit. Anybody living in the 20th century knows that it is completely impossible to be totally objective…but that’s not to say that truth isn’t real. There is a difference between objectivity and truth. At its best, documentary film is about the truth. It’s about reality in a complex way.”

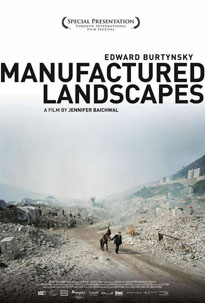

Like The True Meaning of Pictures, Manufactured Landscapes examines the work of another famous contemporary photographer, Edward Burtynsky. Burtynsky is famous for his photographs of landscapes around the world that have been altered by human technology and manufacturing; mine sites, factories, treatment plants and wastelands. Specifically, Manufactured Landscapes examines towns and cities in China and Indonesia that are entirely devoted to manufacturing consumer goods, be it computer chips, cell phones, toys or steel. Catastrophic and devastating, Burtynsky’s work, and Baichwal’s film awaken us to the sickening and enormous reality of our mass consumption.

I ask if the representation of objectivity through the lens is the reason why Baichwal is drawn to the art of photography as subject matter:

“I have always been interested in art, partly because the meaning in art is irreducible, it can’t be paraphrased. When you are thinking about questions of identity and ethics academically, in a psychological context or a humanitarian context, it takes on a specific type of task. The irreducible nature of art is what intrigues me as all those big questions can be paraphrased, and you are encouraged to do that. Art has a capacity to answer questions about meaning in life in a way that is intellectual, emotional and visceral, instead of just intellectually. That’s why Burtynsky’s work is so interesting to me – how can it awake such a visceral, self reflection of our impact on the planet.”

At this point in our conversation, I can’t help but wish Jennifer Baichwal had been the professor for the documentary film class I took in University. Surprisingly, she reveals that she never went to film school, rather studied philosophy and theology. Reflecting on her beginnings of a filmmaker, she does not view the absence of film school as a fault, but an asset.

“I think you can become intimidated by experience some times instead of encouraged by it. History should be empowering you to act versus making you question every move. I learned by doing and talking to filmmakers.”

So how does one begin the enormous feat of documentary film that deals with such huge questions and issues? I ask Baichwal if she starts working on a film with an overall objective, or if the purpose and meaning of a film comes through the creative process?

“Always both. You always have to start with a plan. Some documentaries start with a script, a shooting script that is. They do most of their work in the pre production and planning phase. We begin working on a film by doing a lot of research around the subject and then we formulate a plan, a rough structure – then we go into the situation and respond to the situation. You have a plan, but you have to be ready to abandon that plan at any given time.”

The last point in her response to my question; you have a plan, but you have to be ready to abandon that plan at any given time, has resonated strongly with me over the past week. It is a simple, yet very wise statement that applies to not just film, but everything.

Baichwal continues:

“If you have such a rigid idea of what you need, you won’t see what’s in front of you. On the other hand if you are totally open to everything then it’s too much you fall into arbitrariness. Shooting for us is an existential stance, a way of being in the world at the moment. Editing is about finding the story and it can take a pretty long time.”

Anyone who has tried to make a film, narrative or documentary, knows that it is far more complicated than simply shooting. Beyond all the skills required in pre-production, shooting and post – what will raise a documentary filmmaker’s work from substantial to extreme significance will be their intrinsic personal skills.

Referring back to my first question and Baichwal’s response, if a film can not achieve total objectivity but can capture the truth of reality, how does one achieve truth?

She admits that it was a process of discovery but that empathy and kindness is the key.

“You can be kind while being critical; kindness is the key to finding the truth in a situation.”

With great efforts, intellect and talent – and through all her films, Baichwal has unveiled truth on newly learned realities. With all this work that raises so many questions and opens the flood gates on globally impacting issues – what does she hope to achieve through an audience? A loaded question; she answers honestly and without trepidation:

“I think I would want it to open people’s perspectives about the world. Acknowledging the complexity of reality is important. All of our films live in that place, where there is no easy resolution. The more open you become the more tolerant you are.”

With so many achievements to choose from, what is she most proud of?

“At this stage in my life I’m proud that I’m a good mother and that I can do my work at the same time. I’ve worked out a balance. The children are happy and content but I can also achieve something in my work “

If not traveling the world making films and given a free Saturday in the city to play, how does Jennifer Baichwal like to spend her time?

“My favourite type of day is when I don’t have to get in the car, and I’m simply being a part of my neighbourhood with my family. We can have breakfast at a local spot, go to the park, maybe visit friends around the corner or walk to Christie Pitts. For me, the community and local flavour of our life is very important. I like being in my neighbourhood – my backyard. If I’m not traveling, my universe exists within a five block radius.

So while Jennifer Baichwal may exist in the five blocks surrounding Dupont and Bathurst, her films are shifting the mindsets and values of people all over the world. She embodies the concept of ‘Live Locally, Think Globally.’

I will not forget my conversation with Jennifer Baichwal, like I will not forget about the woman in China sitting in an enormous factory, spending fourteen hour days producing the internal gadgets that go into my computer, which I have already begun to view as outdated.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram