After coming off a three-night cocaine binge to host her son’s first birthday party, Janelle Hanchett sobbed. Riddled with self-disgust, she vowed that this would be the last time. Little could she anticipate that the bottom was a long way down. For some addicts, having a child quells the use. But for others, new motherhood is kerosene for a fire already begun.

After becoming pregnant at twenty-one by a man she’d known three months, Hanchett had embraced new motherhood with fervour. But as the banality of life set in and the pressure mounted, she turned to wine for relief and escape. After the birth of her second child, her longing for redemption was soon thwarted by a descent into full-blown alcoholism.

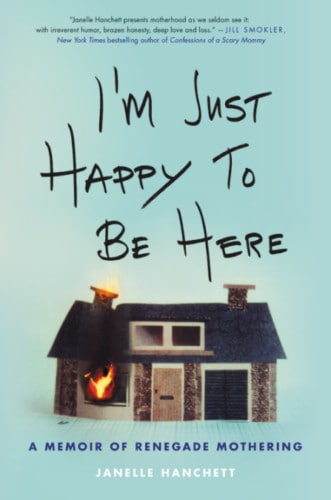

In her stunning memoir, I’m Just Happy To Be Here, Hanchett has painted an honest, unflinching portrait of motherhood, addiction and recovery. Through her wickedly funny and devastating candour, Hanchett shatters the veneer covering the parts of ourselves–our selfishness, arrogance and conceit–that we try so hard to conceal. I’m Just Happy To Be Here is about love, life, pain and loss. It’s about the ties that bind, and how one woman found her way by giving up the wheel.

Janelle Hanchett. Photo: Sarah Maren Photography

We talked with Hanchett about the book this week.

SDTC: What was the hardest part of the book to write?

JH: Definitely the parts where I was really in the throes of alcoholism as it affected my children. When I took Ava to the birthday party when I wasn’t sober, or when the kids went away. The hope I felt surrounding my son’s birth that this was going to fix everything, how grateful I was for him, and how beautiful his birth was, and then knowing what was going to come just a few months later–that was excruciating to write.

How did it feel to include those grim details–like driving intoxicated with your kid in the car–knowing that people were going to read it?

I wrote the entire book pretending that nobody would ever read it. That was the only way I could get it out. If I had been thinking about it being read by an audience, or on a bookshelf at Barnes & Noble, I would not have been able to write it.

I created this sort of vacuum that worked really well–probably too well–because when I turned it in, it dawned on me that it was going to be a book in a bookstore. I had a couple days of panic, but in hindsight, that was a great way to do it.

Were you tempted to gloss over parts, and did you leave parts out?

I wrote about 100,000 words, and the final book was about 89,000, so I cut about 11,000 words. I wrote the whole thing for myself, and then I went back and looked at all the stories. I ruthlessly examined if the story was necessary for the narrative. If it didn’t serve a distinct purpose, I cut it.

I was not interested in shock factor or voyeuristic disaster porn of let’s see how low Janelle could go. That was never my objective. At the same time, I wanted to show the realities of addiction and alcoholism in an unflinching way. I feel like it’s a subject that’s under-addressed as it relates to mothers.

How did you want to address this whole notion of addiction as it relates to motherhood?

I’ve been writing my blog, Renegade Mothering, for over seven years. I’ve landed on various blogs and books from women talking about addiction and motherhood. I’ve noticed the story goes like, “I was an addict/alcoholic, then I stared at my newborn’s toes, or I looked at the positive pregnancy test, and I loved that child so much that I turned my life around and never drank again.” While that is a wonderful story, and I’m happy for people who have done that, it isn’t everyone’s story.

One day I was reading a blog where that was the exact story and I started reading the comments. Many were from children of alcoholics that didn’t get sober. I read what they were writing and saw their pain. I thought to myself, my god, when they read that, they must think to themselves, “Did my mother not love me?” That ripped my heart out. It just tore me in half.

Love is neither the solution nor the problem. And arguing that it is is extremely problematic because an addict needs treatment. Once you’re in the throes of alcoholism, all the love in the world isn’t going to get you sober. That’s the sad and tragic reality that nobody wants to talk about. That’s what I wanted to do with this book: to complicate that narrative of “If you love hard enough, ladies, you can fix this.”

What did you tell your kids about the book?

There aren’t any secrets in my family. Ava (my eldest) remembers when I was gone. I’m not going to sugarcoat or pretend that it didn’t happen. There will never be a time where I will hide from my children what I was. When they are old enough to understand and read that sort of content, they’ll read it. We have an extremely honest, open, trusting family. But I don’t tell them things past their maturity level; they’d be horrified and don’t have the capacity to really comprehend that.

The popularity of your blog would suggest that we’re longing for a more honest and deeper discussion of what motherhood is all about. But it doesn’t seem to cross over into real life. You talk about this whole playground culture, where we talk with other mothers about sleep training and other surface things. Why do you think that is?

I think it’s probably rooted in insecurity. Nobody wants to admit they don’t know what the hell they’re doing, so we put on this front: “I’ve read all the books; everything is under control.”

I don’t blame or judge. There is a ridiculous responsibility placed on mothers, especially in the U.S. We hate mothers in America. We don’t get any paid maternity leave, there are women who are going back to work after four weeks with newborns, trying to work two jobs, we don’t have socialized medicine so we’ve got no healthcare, we’ve got an entire party trying to attack our uteruses (uteri?). So we send these women home with this baby, and we go, “Fuckin’ figure it out! Make money, get healthcare, do everything for your husband, take all the emotional labour of domesticity, don’t mess up, don’t be fat.”

We do a number on mothers, and if we start to admit this complexity and the ambiguity and all the pressure we’ve got, the floodgate would open. So we better talk sleep training so that we don’t talk about this real stuff, because this real stuff is heavy.

You talk about how you got to a point where drinking no longer brought you relief. What brings you relief now?

I have a pretty active spiritual life. I don’t go to church but I pursue spirituality in other ways. Alcoholism is a complex disease of the mind and body, and it gets treated in many ways. One of them, for me, is trying to be of service to others. Trying to stay in gratitude. Trying to help other alcoholics. That helps me a lot because it gets me out of myself.

Alcoholism is a very narcissistic disease. It turns us into extremely self-centred, small-minded and egotistical human beings. Being of service to others brings me relief from the mental noise that often led me to drinking. And writing–that’s been the way I process and deal with the pain that exists internally.

Do you worry about relapse?

Always. That’s why I continue to treat my alcoholism as if I’m a month sober, not nine years sober. I’m always concerned. I see people dying of this disease–they relapse after five, six, ten years. They lose their families, or they don’t make it.

In December 2016, my maternal grandmother was murdered by my cousin. That was the hardest thing I’ve endured in sobriety. That was the first time where it felt like I might not care, that I might actually be willing to drink and deal with the consequences just to have the oblivion that it may offer. So I went back full-force into everything I knew that helped me.

I don’t screw around. If I find myself getting uncomfortable–feeling fear, anxiety and resentment–I address it quickly. I get back to doing those things that bring me relief, that bring me serenity, that remind me that I’m an alcoholic and to drink is to die.

Janelle & her family today

What brings you hope now?

I am excited that we’re here, and our family is what it is. I still can’t believe it. I look at my family and I’m just overwhelmed with the beauty of that. The other night I talking to some addicts and I came home and it was total mayhem: the husband was yelling at the kids to pick up the dinner mess, the three year old was having a tantrum on the floor, the seven year old was running around with a scooter, the teenager was on her phone. It was like a movie.

I looked at this picture and was like, “Holy shit, how lucky am I to be here?” Somebody like me usually ends up in the gutter, or jail, or separated permanently from her family. I got this second lease on life. I know it can happen for anyone. That’s what gives me hope: just living this normal, standard life.

What do you hope readers will take away from your book?

I tried to really tell the truth of the experience as I saw it. I didn’t want to sugarcoat, I didn’t want to shirk, I didn’t want to paint myself as a victim or a hero. If there’s one thing I want people to take away, it would be along those lines. We can exist in that space. We don’t necessarily become better versions of ourselves just because we have children. And we can function in a beautiful way right from that place of who we are.

Interview has been edited and condensed.

I’m Just Happy To Be Here is out May 1. Order it here.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram