Alicia Wanless-Berk is the brain behind La Generalista, an online publication that investigates influence and propaganda in a digital age. She researches how we shape — and are shaped — by a changing information. As Director of Strategic Communications at The SecDev Foundation, Alicia develops campaigns and strategies for outreach and behavioural change.

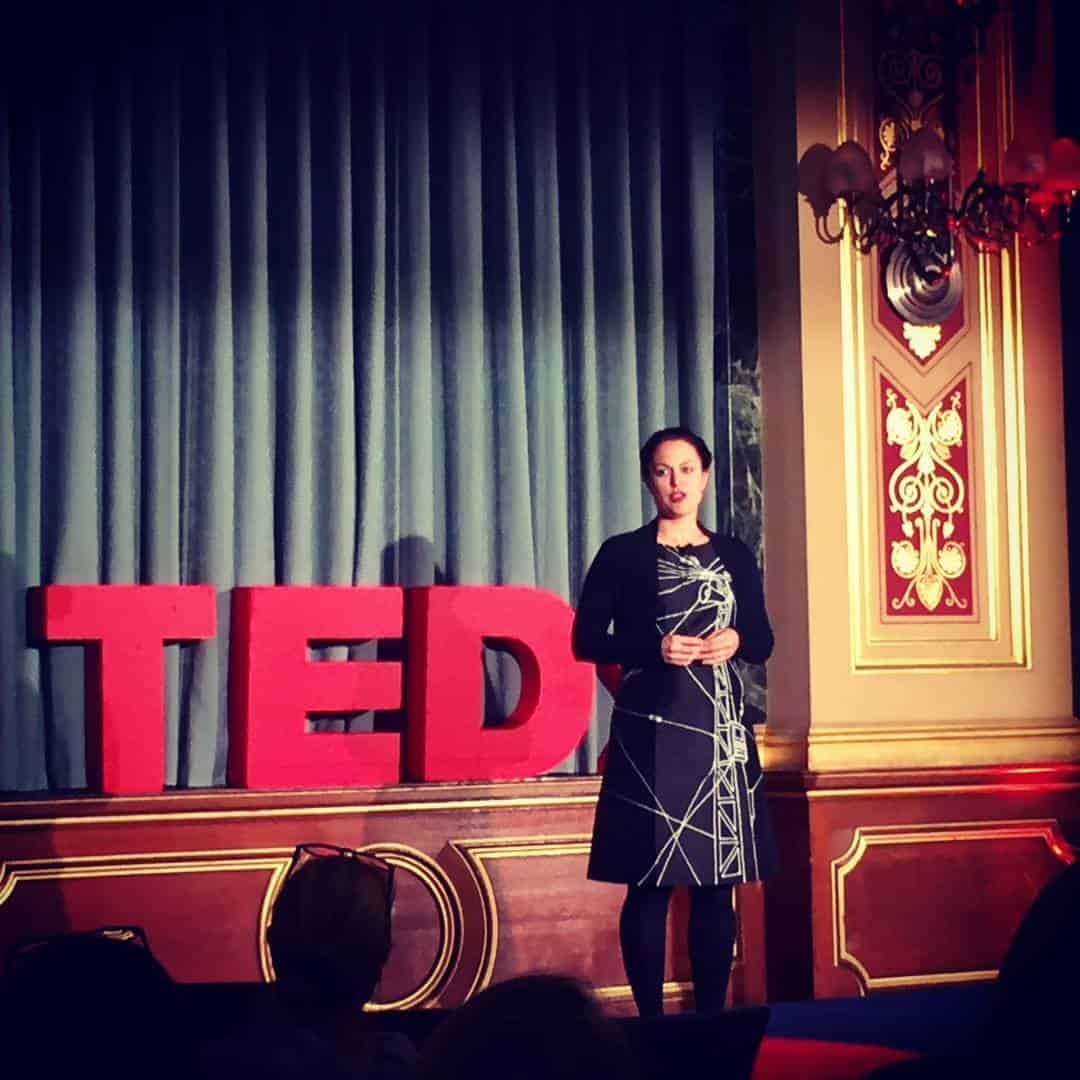

On March 31, she will be presenting a @SMLabTO Research Talk – “Is Digital Propaganda Turning us into Propagandists?” – at Social Media Lab (Ted Rogers School of Management). Get tickets here.

SDTC: What was your education/career trajectory like?

AWB: Graduating with the degree I did, when I did – it’s been much less like a career trajectory and more like a career ricochet. I did my undergrad at York, graduating in 2003 with an Honours B.A. in Russian. It was a really small program, and I was one of two majors who started when I did; the first to do so in several years, and the only graduate when I finished. When I left school, Russia was just coming out of the dark 1990s and there were no jobs for a young person with a liberal arts degree, much less one focused on Russia. I took every opportunity that seemed to pop up and it’s made for a very bizarre, but interesting career path.

Fortunately, it’s been engaging. I’ve been an ICT (information and communications technology) analyst looking at identity-based security measures; worked on a major project for the Nigerian police; handled research and legislative support for a senator; was a coordinator on a G8 Foreign Ministers’ Meeting; ran the regional bicentennial commemorations for the War of 1812; and now am the Director of Strategic Communications at an NGO in Ottawa.

Sometimes it can be a challenge to find the thread that ties it all together, but over the past few years – with our emersion into a growing and all-encompassing information environment – my past work has started to converge in an understanding of how the information space is shaped, and it in turn shapes our perspectives.

For example, without the ICT and security background, I wouldn’t understand how interconnected we are as a society thanks to the internet; without the international and political experience, I wouldn’t understand how different actors are using the internet to shape perspectives, or how regulations could (if at all) be used to stop such manipulation; and without the communications experience, I wouldn’t understand how campaigns work. Take this with my education, which tended to focus on things that leaders use to manipulate the masses, such as language engineering, nationalism, and propaganda, and I now have a fairly rare skill set to look at how propaganda is changing in a Digital Age.

While I wouldn’t change this career ricochet, it makes for some awkward moments at conferences when people ask who you are and what do you do. I still haven’t figured out how to sufficiently answer that question. My answers always seems to lead to more questions.

Can you walk us through a typical day in your life, from getting up until going to bed?

I am not sure that any given day is ever really the same. Mornings are usually filled with daily news. The alarm clock goes off to local news, so I can hear what happened at home. Then I check my email to see what has happened within my network and scan the social feeds to see what’s going on. Next would be to check The New York Times‘ daily brief, both the “here’s what you need to know” written component and the new podcast they launched – but this is really only since Trump was elected. About this time, an alert for any new stories on propaganda will come through, and I’ll check that. I’ll ask my husband what’s come from his feeds – because what he reads is very different from my sources.

If it’s a weekday and I am not travelling, I will start working at my day job. As the Director of Strategic Communications at the SecDev Foundation, my role is very diverse. I support our projects in developing campaigns and strategies to engage beneficiaries in outreach and behavioural change. And what I do on any given day depends on what is happening at work.

By way of example, we’ve hosted an event aimed at hacking conflict with the King and Queen of the Netherlands in attendance. I have developed and delivered training on topics such as verifying user-generated content and how to run an effective campaign in a Digital Age. My favourite work is with my colleague Nada Al-Farhan on digital peace-building between Canadian and Syrian youth, and also providing communications advice to Syrian civil society organizations running their own campaigns. And last week I participated in a workshop on New Diplomacy at Wilton Park in the U.K.

Most of my spare time goes into researching how we shape – and are shaped – by a changing information space. On any given day, I try to wade through what feels like a growing reading list related to the subject. On the weekends, I continue my writing on the subject. Ever so slowly, I am inching towards a book outlining how the internet is used to encourage audiences to become propagandists, drawing from the recent Trump campaign.

What about this new era of digital propaganda do you find most compelling?

I have always been interested in propaganda. There is something captivating about all the ways people come to believe, accept or do things that ordinarily might not be tolerable. In that regard, learning about the First and Second World Wars as a kid sparked my curiosity. Later on I found the works of scientists (such as Stanley Milgram) fascinating, and I have really wanted to understand what motivates people. We have always been susceptible to persuasion, but in the past we consumed less manipulative information – we put down the newspaper, turned off the radio or television, and retreated to our homes. Now, information has almost become all encompassing.

Modern western societies are becoming increasingly dependent on ICTs for their daily life. (A great book on this topic is by Dr. Luciano Floridi, called The Fourth Revolution, in which he describes how we are entering a Hyper Historic state. It’s well worth the read). As of 2015 in the U.S., 21% of American survey respondents indicated they were online “almost constantly.” By the end of the first quarter in 2016, the average American was consuming 10.39 hours of media across devices each day. These rates are only expected to soar.

The problem is, we aren’t really prepared for this always-on life. For example, in Canada, with an internet penetration rate of 85.8%, nearly half of the total Canadian population finished high school before the web was even invented. What can we possibly understand how being plugged in constantly can affect our perception? We just don’t yet have the critical thinking skills to discern good information from bad, particularly in real-time and with how little consideration we give, say, a Facebook post from a friend before we click “like” and share. However, there are those who are gaining deeper insight into how this information environment can be manipulated, and thus persuade people on very important decisions, such as how to vote in an election or referendum.

Any big misconceptions about propaganda you’d like to dispel?

Yes, two.

The first is that propaganda is not simply what the enemy does. It comes in many forms. At its most basic definition, it is the sharing of information to propagate a specific idea. Of course, there are many other definitions, but I think it’s important to consider it at a root level. Propaganda is about persuading an audience to do or think something, and it can come in many forms: political campaigns, advertising, or information warfare. Propaganda is all around us, and sometimes it comes from people we like and not the enemy, and that sort of persuasive information from likeable sources is actually far more dangerous, as we are more psychologically inclined to accept information from such sources.

The second is that we are all susceptible to propaganda, although none of us wish to admit it. There are many cognitive biases that affect how we perceive information and act on it. For example, illusory superiority leads us to believe that we are all better than the average – how could we possibly fall for manipulative tactics? Yet the problem is there are dozens of heuristics and cognitive biases that can trip up our thinking. (This infographic is great for a quick and dirty look at thinking traps.) What’s more, savvy marketers and campaigners understand this about human thinking and use it to their advantage when creating content – content that has the intent of provoking a response in an audience.

What should we be paying more attention to?

I think we need to become more introspective. No tool will save us from ourselves. Instead, the brain needs to be retrained to follow a set of quick questions around thinking errors whenever new information is encountered, in a similar way to how Cognitive Behavioural Therapy works.

You see a Facebook post from a friend, it conforms to your existing beliefs, your urge is to click like and share, but the first question that should always be asked is, “How do I know this information is accurate?” followed by “Who is the source? Do I know where it originates?” and so on.

These don’t have to be deep investigations, but it could be enough to stop the spread of disinformation. And let’s face it, if we want an unpolluted information space, it’s like the physical environment: it comes down to us not to pollute it. We can’t look to big businesses or governments to change things, not entirely.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram