Eden Robinson is loving these book tour days; she can sleep in for once.

While writing her Scotiabank Giller Prize-shortlisted Son of a Trickster, she’d set her alarm for 3:50 a.m.

“I had a lot of personal and professional obligations, so the only time I had to write was between four and five in the morning,” she says over the phone from her hotel room in Granville Island. “I was very conscious that I only had an hour. I had my desk, my computer, my coffee mug—it all had to be in the same place. It was pretty sad. I wasn’t like that before; I could write eighteen hours a day in a hotel room, on a plane. The routine is just more so I don’t go on Facebook; the siren call of ‘research,’” she laughs. “Now that I have more freedom, it’s necessary to have a routine, which is frustrating because I don’t need to be up that early.”

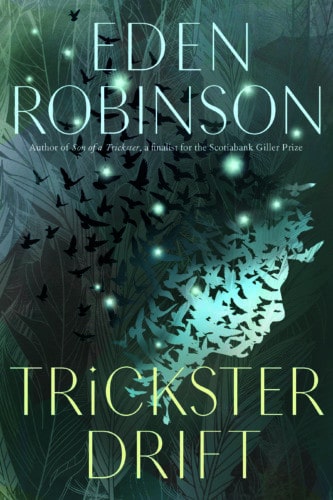

With the release of her second novel in the trilogy, Trickster Drift, Robinson has some time to think about the character who has overtaken her life the past few years. “I found [the Trickster] very irritating—bragging a lot and making a lot of excuses for his behaviour. I thought, you know, I don’t want to spend a novel with you.” Instead, she hones the focus on his reluctant son, Jared. “He’s a mishmash of people that I know and characters that I’ve read. I could not have predicted his love of Nickelback, though,” she laughs. “That was a gift from the muse.”

In Trickster Drift, Jared is newly sober and starting school in Vancouver, but his days of grappling with supernatural forces are far from over. An avid Stephen King fan, Robinson started writing stories whenever she got a chance. Her early works reflected his influence. “Back then it was angsty psychic children, a lot of being possessed by ghosts and murdering people. Pure imitation.”

She picked up a series of McJobs—working during the day so she could continue to write at night. “It gave me an appreciation of what happens to keep our society going and who we value,” she says. “We don’t really value the service industry. It’s affected the characters I want to write about. I’m not interested in characters that have a leisurely life.”

The characters come first, with one or two individuals occupying space in her brain. Then, the story pours out of them. “The thing I fear the most is the actual first draft when you have nothing,” she explains. “It’s the blank page syndrome. But once I’m into it, once it’s cooking, there’s nothing like it. It’s pure bliss.”

For Robinson, writing is a welcome escape from a dismal news cycle. “What really bothered me this past week was the Supreme Court decision that consultation with Indigenous people was not necessary for large infrastructure projects,” she says. “There’s been a lot of talk about reconciliation but what has actually come out has been the same old same old. There are so many ways that the Indigenous peoples of Canada are being seen as obstacles rather than partners.”

Despite all of this, Robinson is looking forward to the future. Her national bestselling novel, Monkey Beach, is currently being turned into a film. And she gets a charge out of the next generation of writers. “The younger writers are balls to the wall with the truth. They’re going to say it no matter what other people think or react. I’m really enjoying that. The generation coming up has it together, so I think we’re in good hands.”

Haisla/Heiltsuk novelist Eden Robinson is the author of Monkey Beach, winner of the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize and finalist for the Scotiabank Giller Prize and the Governor General’s Award for Fiction. Son of a Trickster was also a finalist for the Scotiabank Giller Prize. In 2017, she won the Writers’ Trust of Canada Fellowship. Her latest novel is Trickster Drift. Robinson will be interviewed by Governor General Award-winning Métis writer Cherie Dimaline on October 24 at this year’s Toronto International Festival of Authors.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram