In our culture, persecuting a person for their race or religion is generally frowned upon. But discriminating against someone based on their size? That still gets a pass.

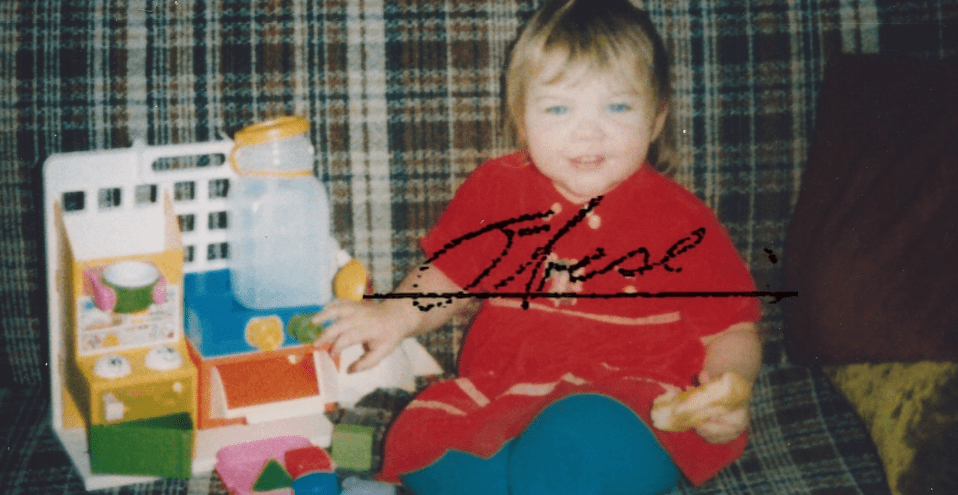

In the searing new film Love Starved: More Than Fat, filmmaker Allison Stevens combs through her own personal history—spanning journals, artwork, and family photos—in order to understand her shame towards her own body. When her childhood medical records reveal that she was labelled obese at three years old, she questions when being fat became a choice. As she reflects on the negative messages that have been imprinted upon her body, she must confront her core insecurities.

We asked her about the film this week.

SDTC: What did you think when you first uncovered your childhood medical records?

AS: I was both super curious and weirdly nervous about what I might find in my records. After I made my personal health information request, I was allowed one hour to look at my records with a staff member in the room with me. I had to decide which ones I wanted to copy, at $0.75 per microfilmed page (plus a basic $25 administrative fee).

I opened the file and found my birth entry! I was in awe, excited. The moment I entered this world was represented in a black and white photocopy of an uneven, microfilmed, thirty-two-year-old record. I shuffled through the papers, trying to find any listings of my weight, putting them aside to keep. When I saw the “big baby” and “chubby at birth” comments, I was surprised, a little confused why they would write that. I was shocked the first time I saw myself listed as “obese” at three years old. I was so young. From that point on, pretty much every record lists me as obese.

I became indignant. How dare these doctors and nurses label a young child as obese? How dare they note and assess my body size, when I was going to emergency for an asthma attack? The records brought up these memories of being weighed at medical appointments, of stepping on the scale and the nurse tsking disapprovingly at my weight. I recall doctors telling my mom (and then me when I was older) how my weight was a serious problem. My mom would get mad every time the scale showed that my weight had increased.

At six, I remember being hooked up to machines and running on a treadmill and feeling self-conscious about people watching me huff and puff. Afterwards, the doctors told my mom I would lose weight, if I was just more active, which they noted in the report. I remember the embarrassment of nurses trying to get my blood pressure, but the sleeve was always too small to fit around my arm and it wouldn’t stay closed, even when I was a kid. One of the nurses told me they had never had to use an adult cuff on a child before.

All those times when I felt like the doctors and nurses were looking at me judgmentally, assessing me as abnormal in some way, it turns out that they were, because they then wrote it in my file. I was reluctant—ashamed—to get weighed, because I knew how people, including medical personnel, would react. And I knew my body was abnormal in other ways—I started puberty exceedingly young—and those same surprised, concerned, frustrated, pitiful reactions to my body led me to not want to show or talk about my body with anybody, even doctors.

Rationally, I understand why all those observations and recordings of weight are there in my file. And in some ways, I appreciate that they are, to help me understand myself through these records. Obesity is a medical term. It shouldn’t hurt. But it does. Because societally, we’ve assessed fat, obesity, large sizes, and extra weight on bodies to be a negative thing. So it’s not a simple, objective medical descriptor; it’s weighted with negative meaning. And that negative meaning was imprinted onto my young body, starting at three years old in the medical records and in every experience I had where people assessed me and my body as problematic.

As I continued looking through the records, I got angry. Very, very angry. And sad. I was in this small office with this staff member—this stranger—while I was trying to control my emotions, to not exclaim my anger—or worse, cry in front of her. And I was also panicking, with only an hour in the office, I had push my emotions aside to focus on the words and decide which records to copy. While scanning over each report, I had to question myself, is this page worth $0.75 cents to keep? (In the end, it cost me $75.)

Later on, I read the copies more thoroughly. My records are interesting in that they reveal this intersection of clinical perceptions and assessments and the limitations of the medical system with the socio-economic conditions of my childhood, the feminization of poverty, and the affect of disabilities on families. We were on social assistance, my mom was a single mother with three kids, and my sister has a chronic physical disability. My health records show how my mom is clearly concerned about my obesity and is struggling with how to manage it. But caring for my sister’s medical needs was her priority. My mom had to make choices in meeting her children’s medical needs, and mine were less critical, because I was abnormally overweight, not seriously ill. Those records were devastating to read.

And they show that there were all these people who were looking at me and saying I had a problem, but that didn’t lead to any solutions. The doctors did tests on me and gave general recommendations on diet and exercise, but the reality of life is much more complicated. And, they clearly missed diagnosing me with polycystic ovary syndrome in my teens.

So that little girl was at the mercy of so much beyond her control, with a biological predisposition to obesity that flourished in stressful socioeconomic conditions, but she was taught by society to be ashamed of her body and to blame and hate herself because of her weight. Going through those records, I was livid—beyond angry—and hurt. I feel like in some ways the medical system failed me. My parents failed me. And I failed myself, because I wasn’t honest about my own experiences of my body, because I was ashamed. But I also recognize that it’s complicated. People did what they thought was best at the time or did the only things they thought they could do.

More than anything, though, being able to see my medical records was incredibly validating. My experiences were real. It wasn’t like I made this decision as an adult to become fat. It wasn’t a personal choice due to laziness and gluttony. It’s been true my whole life, and I have the proof. For me, being fat isn’t an abnormal, negative, and shameful state of being—it is my natural state of being, from the moment I was born. How else can one explain being “chubby at birth” or an obese three-year-old? Those judgments that were pressed upon me and then internalized were unjust. They were wrong. And that recognition that I am not just some broken, pathetic person because of my weight was liberating.

Reading the official medical perspectives of my childhood experiences was also enlightening. In one of the medical records, a doctor noted that I was delayed in my hand-eye coordination and balance, so they recommended that I work with an educational assistant at my school to improve them. That explained all those weird times I was taken out of class with two kids who were developmentally delayed. We’d go to the locker room and throw a ball back and forth or jump on a small trampoline. I never understood why we did that, but I didn’t think I was “special” in the way those other kids were. (But we became friends!) Later, the same teaching assistant tested my reading ability and was visibly shocked that my score was much higher than average. I remember feeling offended that she was surprised I was so smart, just because I couldn’t catch a ball.

How did making this film affect you emotionally?

Making this film was emotionally exhausting, but incredibly empowering. I made it out of a desperate need to heal and be able to love and accept myself and my body. I had been in a life-threatening car accident, which caused me to evaluate my life and the ways that my shame and anxieties were holding me back from truly living. I wanted to be in a loving relationship, but I was so ashamed of my body that I avoided relationships. I had been in a state of self-imposed chronic loneliness for years. But I couldn’t live like that anymore. I recognized that I either had to deal with the ugliness inside me and create a better life for myself or I would eventually commit suicide. Thankfully, art and writing were the coping mechanisms that I’d used throughout my life to deal with my emotions, so I had lots of artwork and material to use in my film!

It started with the memory of being weighed in front of the class when I was in grade 2. I allowed myself to really remember and experience those feelings again, then I wrote them all down. Over the course of several weeks, I thought about all the other times where people made me feel ashamed, embarrassed, or humiliated because of my body. In the end, it was like twenty typed pages of hard, sad writing, but it was cathartic. I had to cut down a lot and focus on the more significant or relatable experiences or stories that I could visually represent.

I also went through my old schoolwork, artwork, personal diaries and journals, family photos, any personal records I had. A lot of work went into finding them, sorting through everything, and then sloooowly scanning them at a high resolution. Initially, I was interested in representations of my self. I was curious, what did I look like in the photos and how did I draw myself at that age? Some parts of that process were fun and amusing. I was cute kid! And there were some really fond memories that came up in the photos.

And I’m impressed at my own artistic ability at such a young age, ha. The artwork spans my lifetime, from my childhood to when I was in college. So I felt a lot of pride in reviewing my own work. It was also really fun animating the drawings from when I was little.

The journals and diaries were really hard to read. There’s a lot of ugliness there. In an entry when I was eleven, I say that I’d been thinking about suicide. I remember at the time, I felt guilty and afraid to write that in my diary. It hadn’t been the first time I thought about it, but it was the first time I admitted it on paper. And I was both afraid and hopeful that someone else would read it and recognize that I was not okay. (Nobody did.) And there are clearly moments where I question how other people in my life have the right to make me feel bad about myself and my body. I feel a child’s sense of injustice at the unfairness of it all.

In my adult journals, I expressed a lot of disgust at myself. I felt unworthy of love. I didn’t even deserve to love myself. I saw myself as a weak person who deserved all of the negative comments and judgments that I received from other people. I thought that maybe if I was brutally honest with myself about all my own physical and emotional failings, I could somehow motivate myself to change. But I was never able to hate myself into losing weight.

I still felt those deep-seated feelings of inadequacy and brokenness when I started making the film, so it was an honest, raw exposure to my deepest fears. It was draining! I never cried so much as I did writing the script for the film. I went through deep, heart-wrenching pain, moments where I was just sobbing while I was typing away. I relived and grieved those painful experiences. And I was in therapy at the time, which helped me come to terms with aspects of my childhood and how it affected me.

As I explored and expressed these memories and my feelings, I was also trying to challenge them. That was the whole point, to come to accept myself and my body. At first it felt forced; I was trying to talk myself into feeling different. It took me a long time to actually change how I viewed myself. It’s still an ongoing process.

The first version of the film was an expanded cinema performance, where I narrated it live in front on an audience. That was a terrifying experience, but it allowed me to release all the sadness and anger that had been building for months. It felt good to share those emotions with the audience. And the response was amazing, really affirming. I had been afraid that I was crazy and foolish to make this deeply personal film, and I didn’t know if people would be able to relate with my experiences. But I discovered that people connect in their own way. And there was so much love in that room from the audience. Afterwards I felt relieved and powerful and grateful that I had these creative gifts that allowed me to share my experiences and perspectives with other people, that I could help myself and help other people through my film.

I filmed that first performance, but it was very hard to watch myself, both seeing my body and witnessing my pain. The film evolved over time, as I continued to work through the depth and source of shame about my body and my feelings of unlovability, so the narration changed. I had to film myself many times, alone and topless in my basement, exposing my vulnerability to the camera. That was really hard to edit, watching those clips over and over again.

I don’t like watching the film, because it makes me really sad to see myself raw like that, but I do enjoy performing it. I still occasionally do expanded cinema performances of the film, where I narrate it live. And every time, I relive all those experiences and feel those strong sad and angry emotions, but it is incredibly empowering and cathartic. Making the film really was a healing process.

If you could go back and say anything to your eight-year-old self, what would it be?

To little me:

You are honestly amazing. You are such a wonderful, worthwhile person. You have such a huge capacity for love and creativity and kindness and so many gifts to share with the world. It’s okay that you’re different from other people. It’s okay that your body isn’t the same as the other kids’. It’s okay that you’re smart and thoughtful and have lots of emotions. There’s nothing wrong with you on the inside or the outside. You are great just the way you are!

And you are sooo, so, so, loveable. They might not tell you all the time, but there are many, many people who care about and appreciate you for you. Don’t be afraid or ashamed to just be yourself and express who you are with the world. And when someone says something mean about you or your body, it’s because they have their own issues. It’s not about you. Don’t be afraid or embarrassed to express your thoughts and feelings, and keep drawing, keep writing, keep thinking, keep questioning.

What do you want people to understand about being a fat person?

For those random strangers out there:

I am a human being. I have feelings. My body is a part of me and I need it to live. It is not an offensive creature that hulks around the streets terrorizing people. You don’t need to be afraid of it; it will not hurt you. It might take up more space than other bodies, but it won’t gobble you up whole. (I promise!) It’s just like your body: it likes to move around and do things. In the same ways that you like to express yourself in your body, I also like to express myself in my body. So please don’t deride us or call us names as we go about our business. Just let bodies be bodies. They naturally come in different shapes and sizes.

To parents/concerned loved ones:

Shaming someone about their weight is an incredibly ineffective way to motivate them to lose weight. It actually has the opposite effect, because it causes people distress and makes them feel less capable. So if there is someone in your life who is overweight and you want to help them, tell them everything you love about them. Tell them all the reasons why they are important to you and how they are worthwhile.

Don’t focus on what you see as their flaws. Show them your love, not your hate. Because hating on their bodies is hating on them. And if you really want what’s best for them, why are you making them feel awful about themselves? That’s not love. That’s bullying. You are not helping them by making them feel bad! You are 100% making it worse.

And if you look at someone you care about but just can’t get past their weight, please ask yourself: Do you really want what’s best for this person or is it about yourself and your own issues? What are your motivations for trying to dictate their weight and self-esteem?What gives you the right to decide how someone else’s body should be?

For those fitness/weight-loss “experts”:

Fat is not a simple equation of eat less and exercise more. Being fat doesn’t mean someone is lazy or undisciplined. It is so much more complicated than that. There’s a movement about health at every size, which has a lot of research that shows you can be healthy and be fat. It’s not accurate to assume that someone is unhealthy because they are bigger.

It’s pretty silly to assume that you know someone’s life story, their abilities and failings, and medical history just by looking at their body. There is so much unseen that is beautiful and wonderful about people, but you can only discover that if you put your assumptions and prejudices aside.

What do you hope audiences take away from this film?

The last lines of my film are the messages that I hope will resonate with people: The body does not determine the value of a person.

What we can contribute to this world exists independently of what we look like or what physical shape we have. Our bodies—our personhoods—are worthy of love and respect. So don’t let yourself be defined by your physical characteristics! And likewise, don’t judge other people by their appearances. Nobody should feel like they are unlovable or not good enough. Everyone is deserving of love!

Also, shame is incredibly powerful when we let it have power over us. There are many ways in which we might feel like there is something wrong with us, that we don’t match up to other people, or that we’re not good enough. And we often keep those fears close to us, hidden deep inside. But that’s where they are most powerful. When we bring those feelings into the open, express them and challenge them, and invite other people into the conversation, we can overcome them. And we’re way stronger than we think we are—we’re totally capable of facing our fears. Plus it feels great in the end! Finally, weighing kids in class is not an appropriate math lesson! Teachers, have some sensitivity to not highlight and expose children’s differences in the classroom.

Love Starved: More Than Fat premieres at Breakthroughs Film Festival on June 8. Get tix here.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram