Imagine being wrenched from everything you know – your friends, your job, your home, your family – just to be dropped in a foreign land with only the clothes on your back.

That is the bitter reality facing 21.3 million refugees across the globe, and over half of them are under eighteen.

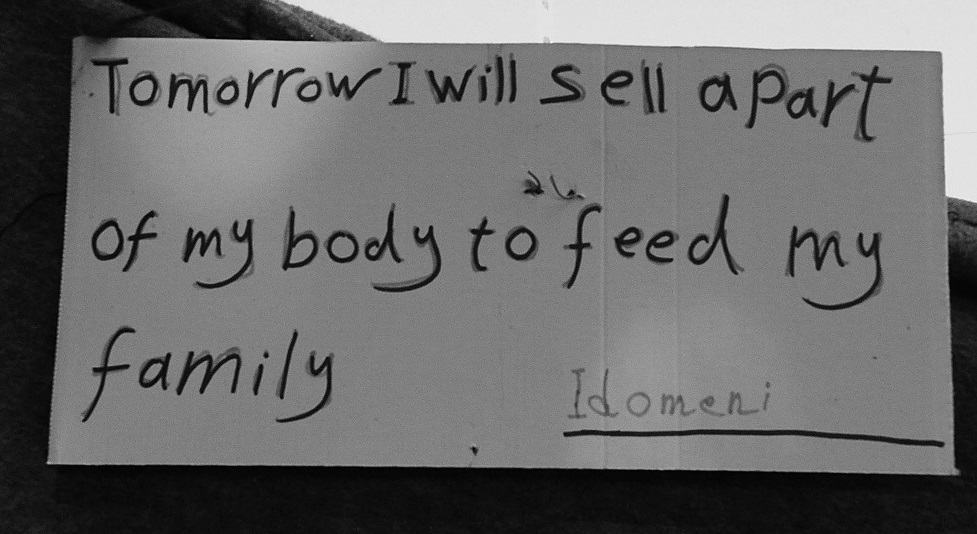

In Fantassút/Rain on the Borders, Toronto filmmaker Federica Foglia turns her lens onto those in limbo at Idomeni, the biggest refugee camp in Europe. This heart-wrenching window into the lives of the people she met forces us to confront our own preconceptions about refugees. Through stark, poignant vignettes and interviews, it underscores the dire situation in which so many refugees find themselves.

We asked Foglia about the film last week.

SDTC: While making this film, whose story resonated with you the most and why?

FF: Without any doubt it was the story of Bilal, an eleven-year-old boy from Syria. An orphan living with his nine-year-old sister in an abandoned train wagon, he had created his own parallel universe: he started a makeshift school where he would teach English to kids of all ages. It was a complete contrast to the misery of the camps.

One day a fellow volunteer in the camp told me, “Go look for this kid and bring him a dictionary.” He emailed a photo of Bilal. I was surprised, as usually kids would ask for balloons or cookies. The only thing I knew was his name. I had his photo and I knew the area of the camp where he might be. I started asking everyone if they had seen this kid, showing them the photo.

Finally I found him. “You are Bilal?” “Yes I am Bilal the teacher!” and he jumped for joy, grabbed the dictionary, the pens and the notebooks and took me to his school, which was a small abandoned shack. His students would sit and listen to his lessons. He used a sharpie and the wall as a chalkboard. I was in awe, this little kid understanding the value of teaching other kids and using this school to detach himself from the inhumane reality of the camp, giving himself and the kids something to look forward to daily.

He created a little oasis of normality. He was so focused and driven by his passion and he had a strength that I have rarely seen in any human being. He was right: he is a teacher. He taught me the biggest lesson, which was about creating something good out of the most miserable and dehumanizing environment/situation, thanks to resilience and drive.

How did making this film alter your own perspective?

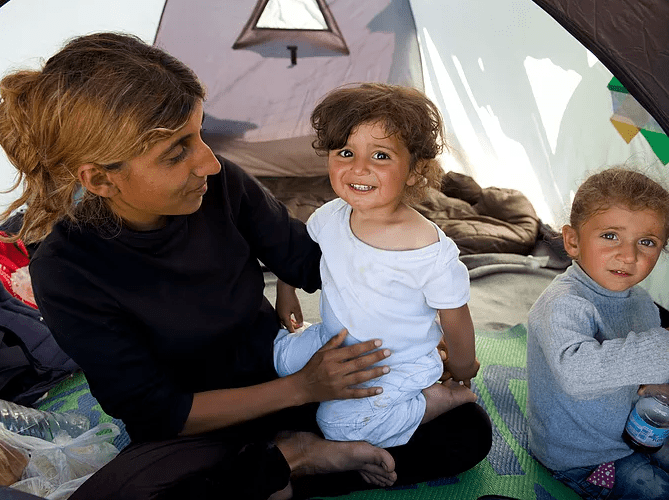

I entered Idomeni with some preconceptions generated by the media. I discovered a reality that was much more intricate, more human, because of the dignity, the sense of pride and communion, the great strength, the ability of still being able to smile, the endless hope of the refugees, and above all, their generosity. Walking around the camp, I was given fresh fruit and so many flowers.

One day I was leaving the camp and I heard a little girl screaming, “My friend! My friend!” (That’s one of the few English expressions the children know and they use it all the time to attract the attention of the volunteers.) I thought, “I hope this little girl is not coming to ask me for food or cookies because I’ve given everything away and have nothing to give her.” As she approached me she said, “My friend, for you,” and she offered me a little wild daisy and ran off through the fields.

After leaving the camps, I went to visit the Parthenon in Athens for the first time. It felt surreal to be in the country known as the cradle of civilization and democracy; centuries later it has been transformed into a purgatory for lost souls.

Since completing the film, have you been in contact with any of the people from Idomeni? If so, what is their situation now?

I just finished talking via Messenger to Mohammed, an ex-pharmacist who lost his wife in the Syrian conflict. He is the father of a five-year-old boy, Abud. We talk almost every day. I feel a responsibility of not letting them feel abandoned, constantly distracting them, and giving them something to look forward to. We plan future birthdays, we send each other small vocal notes, photographs. I show them the first flowers blooming in my garden and ask for medical advice for my aches.

It’s a little hard to properly communicate because of the language barrier, so you have to find alternative ways of conveying a message of love and care. Most of the time their English is very limited, and I certainly don’t speak Arabic, so it requires an incredible effort in understanding each other. We manage, thanks to Google Translate and emojis.

Most of the refugees we got to know in Idomeni are still in other refugee camps across Greece, waiting to be resettled in other European countries. The process is so long and discouraging and on certain days it is really hard to keep them positive. Some of the camps are obscene, [according to] comments from volunteers that are still on the ground. The Oreokastro camp is one of those. People have been left out in the cold winter snow – children included.

On a monthly basis, I try to collect money and send it to them through money transfers/offices that have locations worldwide. This way I know they have a little bit of cash and really basic things that they otherwise wouldn’t have. The European Union has really mishandled this situation, mismanaging money that has ended up in the pockets of the middle men of bureaucracy. That’s why NGOs and private volunteers are so important.

The refugees I’ve left behind are always in my thoughts, even the families I did not manage to keep in touch with. Ironically, they are the ones I think about the most.

A little child – Roshna – was so bright and smart and grew attached to me. I gifted her a small English/Arabic dictionary and wrote my name and contacts in the first page. Then I told her, “One day when you are out of the camp, look for me.” I’m always hoping that one day she’ll contact me. Even if it takes fifty years.

What tangible things can we do to help this situation?

There are many ways of helping. What I really understood after my trip to the camps is that every little bit counts, even if it seems like a drop in the ocean.

The private sponsorship system that Canada put in place was regarded as highly innovative, but it has now been stopped. According to Canada Immigration Statistics, Canada has taken in approximately forty thousand refugees since 2015. This may seem like a lot, but Germany – a country so much smaller than Canada – has taken in about one million refugees in just one year. We can do more and better. We should keep asking the government to do more. I’d love to see Justin Trudeau visit the refugee camps where the real people are – aside from welcoming them at Toronto Pearson Airport.

Donating to select NGOs is another great way of helping. These NGOs are on the ground doing things: Doctor’s Without Borders, UNICEF, the Red Cross, Hot Food Idomeni.

What do you want viewers to take away from your film?

I would love the audience to be reminded that everyone’s existence is fragile. They should feel outraged that refugees’ basic human rights are not being respected. Refugees have the right to asylum. The majority of the refugees had a wonderful life that suddenly turned into a living hell. We all should feel much more than empathy; we should feel outrage.

Being European, I know that my continent was devastated by two world wars. Many of us became refugees. Some Polish refugees in World War II fled to Iraq to seek safety. It seems a remote thought, but what if this happened in Canada? How would we want to be treated if we were the refugees? Would we want the world to help us or to think of us as a threat and build a wall to keep us out?

As contemporary philosopher Thomas Cristiano says, “It is a fundamental duty of the international community to help out with the refugee problem. This means that one must accept some risk. Morality is never costless or risk-free. But we do owe it to our fellow human beings.”

Fantassút/Rain on the Borders screens Friday, March 31 at 6:30 p.m. at part of TIFF’s Human Rights Watch Film Festival (March 29-April 6 at TIFF Bell Lightbox (350 King St. W). Get tickets here.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram