OCAD’s annual GradEx show is now running, and includes work by over 500 emerging artists. This year, more than others, we’ve noticed that there is a sizeable collection of art that sparks ideas and conversation about heritage, be it artists exploring and expressing their identity and sense of self through their art and/or using it to draw attention to racism and cultural stereotypes.

As it is Asian Heritage Month, we wanted to publish a series that spotlights daring artists who are exploring their Asian culture through their art.

Born in Seoul, South Korea, Jamie Park is a curator and artist with a special interest of creating art that raises discussion and ideas around language and identity.

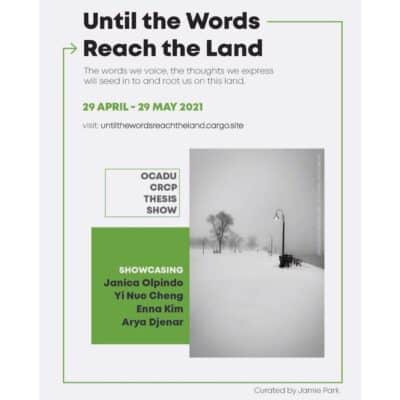

For GradEx, Jamie curated the group show, Until The Words Reach The Land, which explores how language connects us to the land, specifically from the perspective of artists of the Asian diaspora, living in Toronto. “Until The Words Reach The Land is our utterance and affirmation that the land we occupy is our home as well, where we developed our complex identities and where we continue to explore ourselves,” she writes.

We connected with Jamie to dig deeper.

See full exhibit at https://untilthewordsreachtheland.cargo.site/.

What inspired this show?

The historical roots of this exhibition stemmed from my fixation on how language works phenomenologically. My thesis proposal initially proposed a project where I work more extensively on language theories and language transformation. I narrowed down the project to deal specifically with Asian language, ultimately demystifying Asian language in an era of hyper-multiculturalism. I was inspired by Chinese artist Xu Bing to work with language, break the language barrier between cultures, and look to scholarly articles related to him to observe how language works in a multilingual society.

Once I got my submissions, it became more apparent that this piece should gear more towards the topic of Asian Canadian diaspora, allowing more room for relatability, human experiences and how we connect to culture through language.

Artist Jamie Park at work.

Have you been thinking about your heritage differently this year than in the past? If so, how?

I have always been in touch with Korean heritage and culture thanks to my mom, and I’ve been proud of it too. In the past year, I was able to observe how Asian Canadians and Pacific Islanders are perceived in Canada and North America in general. I became more aware of the public societal perception of Asian Canadians, which is that we are outsiders.

Asian Canadians have constantly been perceived as perpetual outsiders, and it shows when we look at how much violence has been enacted on Asian individuals in Canada since the start of the pandemic. And this realization also fuelled my project and my goal to amplify Asian voices, especially their relationship to this land.

HANBOK/한복 by Artist Enna Kim, part of the Until The Words Reach The Land group exhibit, curated by Jamie Park

What part of your heritage are you most proud of / enjoy celebrating?

The part of my Korean heritage that I am most proud of is the Korean people’s political history of fighting for democracy and their ability to decolonize and spread their heritage throughout the world. Korean people have historically been very much of a dissident group of people, fighting against authorities and colonizers for what they believe to be right, which is evident through The Candle Light Demonstrations back in 2016-2017.

While I am incredibly proud of their political history, I thoroughly enjoy celebrating Korean pop cultures like K-Pop, movies, and drama, especially for their ability to generate soft power and spread our cultural heritage with the rest of the world. For example, K-Pop artists BTS and Black Pink wearing Hanbok, a traditional Korean garment, in their music videos.

What part of your heritage do you think is misunderstood? Or do you wish people knew more about it?

One of the biggest misunderstandings I observe is not specific to Korean heritage but to East Asian culture. I find many people homogenizing east Asian cultures and experiences, and I wish they knew more about the distinct cultural features of different Asian countries. To speak broadly, China, Japan, and Korea may have similarities here and there, but they are all incredibly distinct from one another. For example, all three countries use soya sauce in their cuisines, but their soya sauces taste very distinct from each other. Japan has different soya sauce for multiple different occasions and tends to be sweeter than the other two countries. Chinese soya sauce is light but flavourful and used to season while cooking or Lao chou, which is thick, concentrated soya sauce more for colouring. Korean soya sauce is divided between “jin” and “guk”, one being lighter and more used to season, and the other being darker and saltier and more flavourful. They even use different types of beans, fermentation techniques and differ significantly between flavours.

Similarities exist because we all live in close proximity, and there were lots of exchanges happening over multiple centuries. Still, we have all developed our cultures intricately from this original exchange. We must stray away from the mistake of homogenizing and learn to appreciate cultures for their heritage and culture.

Toronto B-girls is a documentary by Janica Olpindo that highlights the experiences of three different b-girls within ‘breaking’ culture, and part of Until The Words Reach The Land group show, curated by Jamie Park. Watch here.

What conversations or ideas do you hope this works inspires?

While many might claim that identity works are getting overused, I do not believe that we should be ending our conversation on multiculturalism and who belongs where any time soon. Ongoing socio-economic tensions support this belief. Day by day, we see hate crimes and xenophobic crimes against people of colour, and I think it’s important to remind people around us that we, too, belong here. But also remind ourselves not to internalize this hate and violence and question our belonging.

The work aims to affirm our identity, our presence, and our culture within this land. Curating an exhibition formed of Asian diaspora artists during this time of heightened anti-Asian crimes is not a pointed jab back at the racists but an attempt to reground ourselves in our place on this land we call home.

This exhibition is our utterance and affirmation that the land we occupy is just as much our home as well, a land where we develop our complex identities and where we continually explore ourselves.

Artist and Curator Jamie Park

What is the greatest lesson you’ve learned while at OCADU?

The greatest lesson I learned at OCADU is learning to take criticism. OCADU Focuses a lot on peer criticism and has critiques with peers for every project. While professor’s assessments are incredibly to the point, peer criticism in big groups allows you to feel how the public views your project. It’s a collective critique session and gives us all a comfortable room for growth and reflection.

What do you love most about the GradEx show?

Being able to see visually how hard all of my peers worked throughout the year is what I love about the most from this year’s GradEx Show. The pandemic and online school made the beginning of the school term very dim, and I remember multiple conversations with my colleagues about the struggles we had throughout the entire year as we try to churn out our best creativity for our thesis projects. Seeing the final results and projects makes me more than pleased to discover that we all made it through. Also, since everything is virtual and connected to our websites and contacts, it is effortless to look at artists’ other artworks and creative works instantly and conveniently. At the same time, I miss the festivity and liveliness of GradEx that takes place in real life.

Check out all the incredible art at OCAD’s GradEx 106 virtual event now.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram