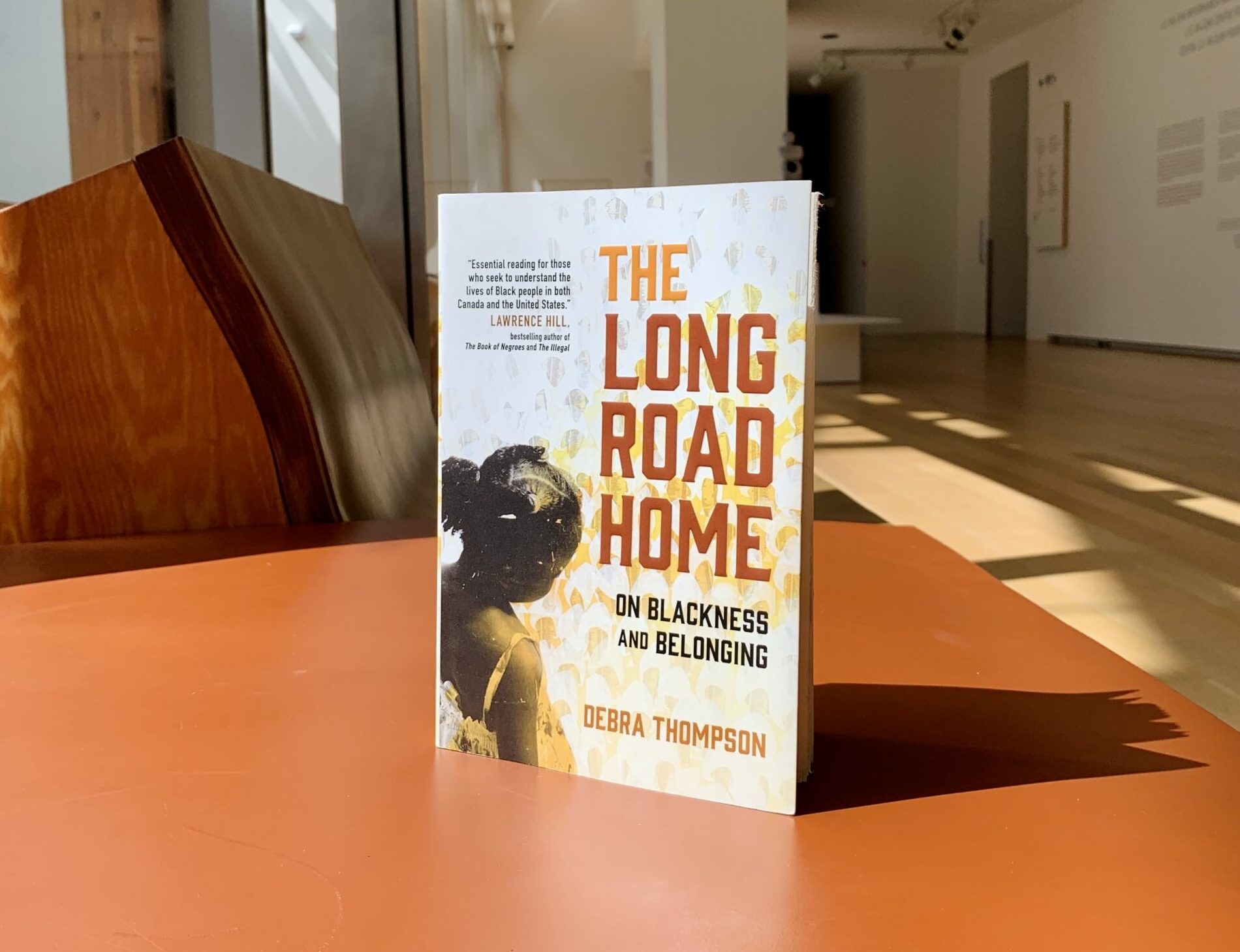

Unique in its style, The Long Road Home: On Blackness and Belonging is a heartfelt memoir that is loaded with historical facts and brilliant analysis on race. We’ve said it before, but it’s a must-read for Canadians.

Thompson writes about her childhood and youth in Ontario, where she felt like the “Only One”, or the only Black person in the room. She goes on to share her experience as a Black woman pursuing a career in academia, earning degrees in both Canada and the United States, and later teaching in both countries.

With painstaking detail, Thompson explores the histories (both known and missing) in the various places she has lived (Boston, Portland, Chicago, Montreal) and shares how those histories, as well as the political climates, impacted her life, and how she was viewed and treated as a Black woman.

The Long Road Home is an enthralling, fascinating and eye-opening read that had us reviewing our own history, while also evaluating our current environment, constantly asking questions like who feels safe here? Who thrives here? How can this space nurture a sense of belonging?

We were lucky to catch up with Thompson, who is currently a Professor of Political Science at McGill Professor, to ask her some questions that the book raised. Like all great teachers, her wonderful responses spark further discussion.

What has writing The Long Road Home: On Blackness and Belonging done for your mind and body? Do you feel a shift? Any kind of relief? Has it taken you to a new place?

I’ve got bad news, folks. Writing this book was actually incredibly stressful. Like many writers, I’ve got a more than full-time day job (as a professor with a flexible schedule but often a 50-hour work week), two small children who don’t care about deadlines, and, perhaps most importantly, decades of racial trauma that was reanimated when I relived the racism of my life and the lives of others in order to get these words down on the page. I knew the moment of “racial reckoning” in the summer of 2020 would be short-lived, so I wrote the book as quickly as I could in the snippets of time between meetings, after my children went to bed, and on weekends, and it took a toll on my mental and physical health. I ended up in the hospital – twice! – because my body just stopped working properly. The point I want to make is that there’s a weight to racism. It seeps into our bodies and souls, and if we’re not careful, it will lead to our untimely demise.

We love how your book balances your own life experiences and stories with a tremendous amount of historical facts. We learned a lot. Can you talk about this choice? To approach the memoir in this way? And how, as a writer, you organized things to strike a balance?

It was challenging to try to strike a balance between the personal angle and the parts of the book that draw from academic research in political science, history, and other social sciences. I was always trying to make the book more about the research and my editors were constantly pushing me to put more “me” in the text. I was quite hesitant about that. I honestly don’t think I’m a particularly interesting person and, as I write in the book, using my experiences as an entry point into a broader inquiry about race, Blackness, and belonging makes me deeply uncomfortable. But two things made me relent. First, I’ve been teaching in university classrooms for a long time, and I’ve learned that the more concrete you make abstract concepts, like democracy and liberalism and freedom and justice and belonging and migration, the more resonant students find these concepts, and the more they can see how the abstract actually affects their day to day lives, how they move through the world, and who they want to be. And that’s an important goal – to make these ideas resonate with the book’s audience, whoever that may be. And secondly, though I’m trained as a political scientist, my intellectual heart is in Black Studies, where storytelling is tradition, repetition is sacred, and writing is the process of turning bewilderment into awe. Centering Black experiences is a longstanding mode of resistance against all those forces that seek to dehumanize Black people. This book was a way for me to build from and honour that tradition.

What feedback have you received since publishing the book that has really struck you? Or maybe a response that has surprised you?

I was shocked that my book is a finalist for the Hilary Weston Writers’ Trust Prize for Nonfiction. Literally speechless. My agent emailed me and said something like, “Before you ask, yes this is a big deal!” because I’ve never had a good sense of the metrics of success for non-academic books, and also because I kind of can’t believe that other people think the book is good. Like, I think it’s good, but I’ve been doing this research for years. I didn’t know how the lessons would land with an audience that perhaps hasn’t thought in a sustained or serious way about racism, diaspora, belonging, democracy, justice, or any of the other complicated ideas I tried to demystify in the book. I’ve also gotten really kind messages from other academics, some of whom have said to me that this is the best book they’ve read in a long time, which is just incredible. I mean, we read books for a living and some of the folks who have messaged me are themselves experts in migration politics or transnational history. To get that kind of praise from my peers is just really special, in part because it means that all kinds of different audiences are still getting something from the book. And my students loved the book. They read it while it was still in draft form, actually. Many of them had already graduated from McGill, but they emailed to say that they bought the book for their siblings or their parents. And, like … wow. I’m so honoured.

What’s your advice to people who feel like they don’t belong, who feel like the Only One, whether that be in Canada or elsewhere?

It’s not that we don’t belong anywhere, it’s that we belong everywhere. Also, that feeling of not belonging is white supremacy at work. Don’t let yourself be tricked by white supremacy. Don’t let yourself be tricked into believing it or protecting it.

In recent years, be it in Montreal or Oregon or wherever, do people still ask you where you are from? If so, how do you respond?

Nobody asked where I was from when I lived in the United States. Everyone just assumed I was African American and even though African Americans have a complicated place in and relationship to American democracy, I really loved the sense of peace that came from others assuming that I was “really” from there.

There are language politics at play in Montreal, which means that I don’t get the “where are you from” question in the same way. It’s complicated. My French still isn’t great, so my interactions with strangers also happen under the assumption that I’m African American, or at least not “from” “here,” where the “here” is now, very specifically, Montreal, since most Montrealers are bilingual. If I were francophone, I think I would perhaps get this question more frequently – many of my francophone Black friends and students do get this question, actually, because “from here” in Quebec is often coded as white francophone Quebecois, even though Black folks have been here for centuries. I don’t know how I would respond. Not by insisting that I’m Canadian; not anymore. I used to ask people to guess and then whether I would lie or tell the truth depended a lot on who was asking and what their intentions seemed to be. But I’m older than I once was, and that means I now care much less about what strangers think of me. Sometimes it’s a wonderous thing, growing old.

What conversations or reflections do you hope white liberals (who’ve perhaps lost momentum in their anti-racist work) will have when reading this book?

One of the things I try to do in the book is to connect micro-level, interpersonal experiences of racism (like, when someone asks you where you’re really from) to meso-level policies, procedures, and institutions that perpetuate racially disparate outcomes or fail to alleviate racial inequities (like, how Canada’s multiculturalism policy was not designed to be an anti-racist instrument) and macro-level structures (like, how white supremacy operates as the invisible but ubiquitous force that underwrites political, economic, and social life). And, unfortunately, there aren’t any individual remedies that will work to change structural racism. That will take sustained, multifaceted, multipronged collective action, which must be as relentless in seeking change as white supremacy is in maintaining the status quo. But if we’re looking for micro-level answers about what individuals can do, another theme of the book is the way that white interlocutors or power brokers helped to change the course of my life by opening doors, by protecting me from institutional racism when they could, by calling out and challenging racism when they saw it happen, by taking on labour for me. And note that this was most effective when it meant that white people put themselves in harm’s way, or gave up power, or sacrificed their reputation or their time or their well-being. If you want to be a good white ally, if you are a white person who has benefited from what the philosopher Charles Mills called the racial contract, but you do not agree with the terms of that contract, then you will have to give up power, or at least use it differently. That’s all there is to it. That’s the price.

This is a big question, the kind that sort of requires a book, but since you’re here, what do you think are the most pressing changes that need to happen in the world of academia in North America?

Huge question. I don’t know, but there are people more qualified than me working on precisely this question. (Sara Ahmed’s On Being Included is a really good place to start, though.) One of the things I’ve been thinking about a lot lately is how I often get put on committees – say, for example, a committee that is supposed to decide which book wins an award – and the committee is me and two white men. Essentially, I am on the committee to ensure that it is “diverse”. And then the inevitable happens – it’s a three-person committee, I get outvoted 2-1, and the decision moves forward as if all the labour I had to put into the committee didn’t matter at all. Because, of course, it didn’t matter at all. So, efforts that appear to support “equity and diversity” end up being a lot of work for me and lead to an end result that seems like it came about as the result of a fair and equitable deliberation process by virtue of my very presence, but was in fact about the appearance of diversity more than a commitment to equity. This kind of thing happens a lot. A. Lot.

What makes you feel hopeful today?

You cannot be a decent teacher without a reservoir of hope for the future and those who will bring it into being. My students are so much wiser, determined, radical, and so much braver than I was at twenty. And they know so much more. They have access to so much more information, they have the ability to find communities of like-minded people, they can learn and debate and grow anywhere, everywhere. They’ll change the world.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram