by Monica Heisey

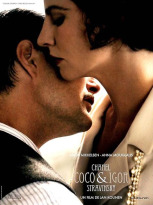

Coco Chanel & Igor Stravinsky might seem like an overly simplistic title for a film about the torrid affair between the French fashion designer and Russian composer, but it actually sets up their dynamic perfectly: Coco comes first. Portrayed as a shrewd, fiercely independent woman who gets what she wants in business and the bedroom, Chanel invites an impoverished Stravinsky (and, ahem, his consumptive wife and three children) to stay at her country estate so he can complete his symphony.

This movie reminded me a great deal of Girl with a Pearl Earring, that 90 minute staring contest between Colin Firth and a young Scarlett Johansson, in that it was beautiful, quiet, and built mostly on sexually charged glances. However, where Firth and Johansson got an electrifying touch of the hands over an easel, Anna Mouglalis and Mads Mikkelsen have a ludicrously hot sexfest on the floor of Chanel’s salon. One slip of the silk nightgown and all bets are off as the two embark on a few weeks of sex and creative output, their romance seemingly informing and inspiring the two; Chanel starts to wear colour and prints, Stravinsky makes great strides in his composing, but his patient wife Katarina (Elena Morozova) wises up to the pair and his marriage is on the brink of dissolution. While the idea of artistic adultery sounds titillating in the highest, the affair seems somewhat drawn out, and Katarina is such a pitiable figure that some of the fun is taken out of the whole ‘illicit sex while your wife is upstairs’ situation.

While 2009’s Coco Avant Chanel had the lovable Audrey Tatou in the titular role, the Chanel of this film and her lover are both immensely unlikeable, a quality that enriches the movie rather than detracting from it. They are both using each other, calculatingly playing with the people in their lives to get what they want. When Chanel gives an anonymous donation to fund Stravinsky’s latest effort, it feels like she’s doing it for a love of music more than love of the man who wrote it. You don’t have to like the characters to like the movie—in fact, deeply disliking the characters was what made it fascinating to watch.

The trilingual film apparently also has an English version, but the mingling of Russian, French and English makes a much more interesting cinematic (and faux-cultural) experience. Qualms with the pacing aside, this film does one thing so, so right: the fashion of Chanel and the music of Stravinsky, the artistic calling that are the real loves of both their lives, permeate the film in a variety of ways; Chanel’s designs inform the aesthetic of the film the way Sex and the City wishes it could have incorporated its Manolos and Dior. While I had my issues with the movie, it has to be said that it was a feast for the eyes, and for lovers of wry, Jazz Age type humour. The film opens with a hypnotic, kaleidoscopic blending of art deco shapes in black and white, the dialogue, décor and cinematography all seem drenched in Chanel’s early twentieth-century modernist ideal. “You don’t like colour very much, Mme. Chanel,” Katarina comments on her new bedroom. “As long as it’s black.” She says. Touché.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram

Earth Month is upon us! What will your pledge

Earth Month is upon us! What will your pledge

We’ve gathered

We’ve gathered