Growing up, we called it The Mission.

As a young person, I didn’t really understand what that meant. We weren’t taught our history. No one in the many Catholic schools I attended broke down the history of Indigenous people in the area and the creation of our reservation.

Fort William First Nation Indian Reserve sits adjacent to Fort William, or “Westfort,” in the city of Thunder Bay, Ontario, and is signed under the Superior-Robinson treaty. Typically, you can access the city via the James Street bridge, which is a rickety wooden swing bridge and railway. I grew up having nightmares about falling off that bridge in cars despite having crossed it hundreds of times. In the summer, we could ride our bikes across it and into Westfort–most people just walked; however, a fire in 2013 burned it up and no one, save for the trains, have been able to cross it since. No one will take responsibility for the damage; therefore, it has yet to be fixed.

The closure has forced folks to take a huge detour across another bridge further down the Kaministiqua River on the highway. This has led to many a devastating car accident due to the precariousness of the turn to get onto Chippewa Road, which leads to the reserve, with the victims being mostly community members.

I’ve learned that just recently (five years later) the bridge is finally being repaired. I haven’t lived on reserve since I was seventeen, but I still and always will consider FWFN my home. That burned bridge represents many things to me: It represents the loss of my way home. It represents history being erased. It represented the divide between us and them. Most importantly, it represents keeping us in our place.

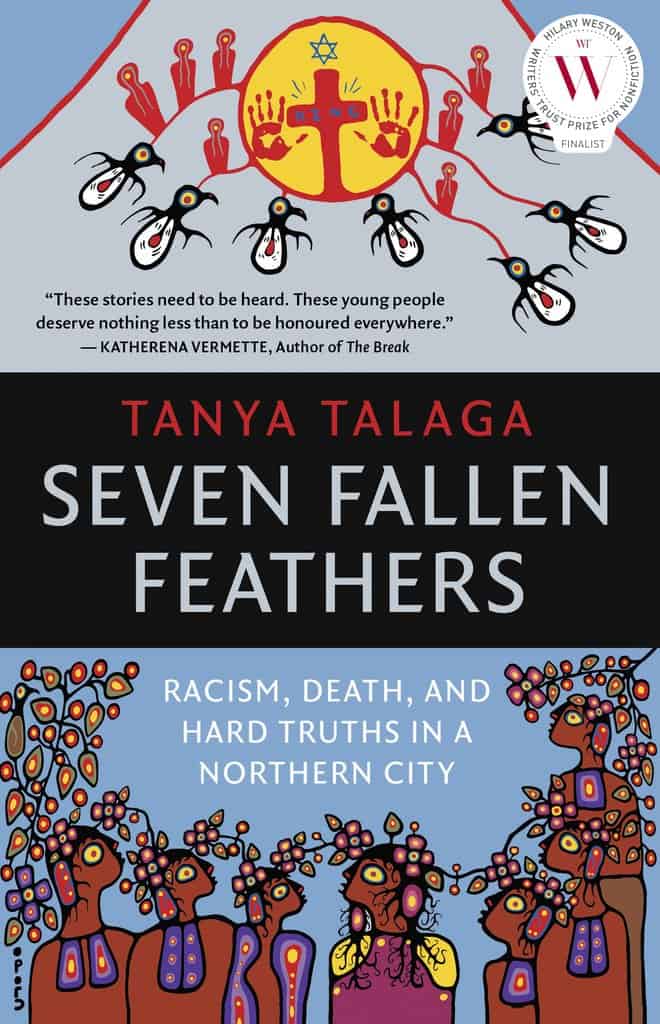

When I picked up Tanya Talaga’s Seven Fallen Feathers, I read her description of this history and more. She begins by telling the story of Nanabijou–The Sleeping Giant and the Ojibwe people. She talks of Thunder Bay being a “city with two faces”–the history of Port Arthur and Fort William and what that means for the Indigenous people that live within it. She paints this as a creation story–an old tale–and it reads beautifully and heartbreaking and we’re only six pages into the book.

Now, I knew what the book was about before purchasing it. The art that I create is based around Indigenous truths and politics, and I try to be aware and fight for our youth and our women and girls as much as possible. I remember hearing about the missing youth while it was happening. I knew what I was getting into. But there was something about reading that prologue that I wasn’t ready to hear. I was barely two pages in and I threw the book down in tears.

I. Wasn’t. Ready.

Growing up, I read as much as I could. I loved reading. Sweet Valley High and Christopher Pike books were so precious to me. I remember my auntie buying me true crime books, so I began a journey into those as well. True stories about daughters or sisters being murdered or missing–white people with the support of thousands behind them. Support of the local TV stations and newspapers. Support enough for a made-for-TV movie or even a book.

Meanwhile, I was completely unaware that thousands of Indigenous woman and girls had gone missing since the seventies and no one was reporting or writing books or CBC specials about that. I had no idea that I was a statistic. That I was five to seven times more likely to die a violent death. Even when I was twelve years old, having just crossed the James Street bridge with my cousin, a white man in a moustache and truck pulled over and tried to get us into his vehicle. Two very young Indigenous girls, clearly coming from the reserve. I didn’t understand the impact and terrifying reality of that situation, even when he opened the passenger door and said, “Get in.” We knew enough to say we weren’t going very far, but thanks anyway, and walk as fast as possible to get further into the city, rather than right beside the docks. At the time, those docks were also being used to traffic young girls into the Lake Superior sex trade, unbeknownst to anyone. Being an Indigenous youth in that city was far more dangerous than any of us had really known, and it hasn’t changed in over twenty years.

There’s something about knowing the truth and reading about the truth. When I picked up the book again, I felt a reflection. I knew every place she was talking about. None of the youth were from FWFN; instead, they were from neighbouring reservations that did not have access to high schools or proper medical care. The kids were sent to Thunder Bay to live with host families–sometimes relatives, oftentimes not. They attended Dennis Franklin Cromarty High School, a school for Indigenous students coming from as many as twenty different communities. They were removed from their homes, which were most often dry reservations, and placed within a city where anything goes and no one was really looking out for them.

Seven Fallen Feathers tells the stories of seven Indigenous high school youth who died in Thunder Bay, five of whom were found in rivers, between 2000 and 2011.

Jethro Anderson.

Curran Strang.

Paul Panacheese.

Robyn Harper.

Reggie Bushie.

Kyle Morrisseau.

Jordan Wabasse.

It also mentions Tammy Keeash and Josiah Begg, two Indigenous teenagers from two different communities found dead in the same river a week and a half apart during the writing of the book itself.

For years, there were no inquests into the deaths of the seven. The police don’t take “drunk Indians” too seriously. The fact that some of these kids were intoxicated means that the manner of their death is insignificant. They did it to themselves. They asked for it. They fell into the river. They walked in. About a million other options except for the obvious one: someone killed them.

It’s no secret that racism is alive and well in my city. The trailer hitch to Barbara Kentner’s abdomen will tell you that. The writing of “INDIAN COCKSUCKERS THROW EM IN DA RIVER” on the back of a city bus seat will also tell you that. That one in particular should be a huge hint that our youth are not just stumbling into the river. Talaga writes about sixteen-year-old Daryl Kakekayash, who was beaten and thrown into the Neebing River by three white men. Through his resilience, he survived and reported it, and nothing came of it. No charges were laid.

When I was in my early twenties, I attended an event called Rock the Fort, which was an outdoor concert held in a field at Old Fort William, a terribly dated re-enactment or “living history” park about thirty minutes outside of the city. It was the middle of the summer, the sun was high and bright and we had zero shade. All I did was drink water and did not move from my chair, but that didn’t stop the sun stroke from getting me. My head began to pound and I could feel myself getting weaker and weaker. My speech was starting to slur. I turned to my girlfriend and said that I needed to go home. We contemplated taking me to the medical tent, but it was on the other side of the field and I could barely walk. There were shuttle buses running all day back and forth into the city and they were all behind a fence, guarded with security. In order to get to the shuttles, we had to walk all the way down the hill and back up on the other side of the fence, unless this guard would let us through the opening that they were using.

We walked up to the guard and my girlfriend said I had heat stroke and we needed to get to the shuttle immediately. The guard looked at me and asked how much I’d had to drink. We both insisted I had only been drinking water, but he didn’t believe me and sent us down the hill, only to have to come back up.

It didn’t occur to me at the time that the question and the decision was racially motivated, because I had convinced myself that if I hung around and dated white people, I would just blend in. Unfortunately, when you’re Indigenous and you look Indigenous and you appear drunk, it doesn’t matter if you’re white girlfriend defends you: you are just another drunk Indian who deserves to suffer. I ended up in the hospital the next day for dehydration.

This is the city we’re dealing with.

So, when none of these deaths are taken seriously, am I surprised? No. Of course not. I am surprised that there are people who still believe these incidents were accidents. White people in Thunder Bay have a deep, deep hatred for Indigenous people. No, not all of them, but A LOT of them. Even the ones who aren’t saying it. The ones who ignore us. The ones who turn away or scroll past the news. The ones who make fun of us for our struggles and pain and coping behaviours from years of intergenerational trauma. The ones with micro-aggressive racist behaviours. The ones who voted for Tamara Johnson, the MP candidate who ran a campaign based on racist ideals and garnered over 900 votes. The ones who call us Redskins or Bogans or Indians. The ones who tell me that I’m different because I can blend in with white folk.

When I was finally able to read Seven Fallen Feathers, I wept through most of it. There was a story for each of the youth. I learned about their family members, who was left behind, who was there with them, who were the ones that were fighting so hard for someone to do something. I learned about the conditions of the reservations in Northwestern Ontario that surround Thunder Bay. I learned about how much privilege I had growing up on Fort William First Nation, despite the conditions I had experienced.

I tell anyone close to me that they need to read this book. Partially so that they have an understanding of where I come from, but also so that they have an understanding of what is happening in their backyards. I know a lot of folks–allies who believe us and want to say all the nice and right words and will come to our keyboard defence, but…how many of you know what Pikwakanagan First Nation looks like? Or where Mishkeegogamang First Nation is? Or even how many communities there are in Ontario? Everyone is upset that they weren’t taught Indigenous history in school, yet no one is willing to pick up a book and teach themselves.

I think what people have to understand is that an act of violence on one Indigenous body is an act of violence on all Indigenous bodies. We are all the same. We have been losing our brothers and sisters for years and years in this ongoing genocide on this land. Unfortunately, Thunder Bay is one example of a hate-filled city (holding one of the highest rates for hate crimes in Canada), but there are cities like this all across this country. Our allies need to do better. Our government definitely needs to do better.

We all just…need to do better. Do more.

McIntyre (Yolanda M. Bonnell, 2017)

For every Indigenous youth that was found in or near the McIntyre River (The River of Tears)

When the splashes rush past

Waking up my cells

Waking up the reeds and minnows

Disturbed my sleepy stillness

Moonlight hits

Blink

Blink

Pain

I feel the stumbles and shoves

I feel the blood of ones connected so deeply to the earth

Hit and mix

My body is a sigh

My body is a healer

My body is medicine

My body

Opens its arms

To welcome another child

Coughing gently and returning back

Like the ashes of sage

Returned to a tree

Skin on my skin

Brown like mud like earth like skin like brown like mud like earth like skin

The violence hangs in the air like a stench

Fogs up the bank

Leaves the tree weeping

Tears of a sorrow so deep it cuts

Through bone

Heart fractures

Wash into me

The ebb

The flow

Become calm

And I go back to waiting

Beneath the moon

For the return

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram