by Amanda Tripp

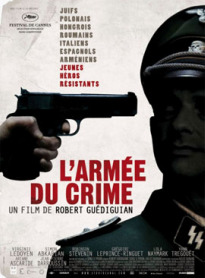

Given the recent successes of Valkyrie and Inglorious Basterds, it goes without saying that this has already been an important year for the resistance film. Rising against a somewhat tired trend, Guédiguain gives us occupied France in a vastly different way. Set in 1941, The Army of Crime (L’Armée du Crime) opens to the naming of men and women said to have died for France: this is recited over an opening sequence where we meet these people as they make their way towards inevitable execution at the hands of their own country. From the outset of the film, then, Guédiguain commits to the conflicts and hypocrisies inherent in resistance narrative, rather than mindlessly glamorizing the just cause. As such the film rallies and grieves simultaneously – a love letter to France written in the blood of the unrequited. Above all, Army of Crime bravely faces us with a France only about to be lost, an idyll the film rapidly debunks despite its own evident longing for the dream to be true. For this reason the film remains painfully honest despite its pull towards the status of emotional epic.

Cinematographer Pierre Milon’s France is incredibly beautiful, sunlit and rich in the way so many film cities ultimately fail to be – Paris’ vibrance is only rivaled by the equally powerful photographic treatment of its underbelly. Alexandre Desplat’s score is touching without forcing the issue, and thanks to the extraordinary talent bringing this film to life, it doesn’t have to. Though it occasionally gives in to unnecessarily expressive superimpositions, the camera is for the most part sophisticated: its greatest skill is in leaving the audience a certain amount of control to draw their own parallels and related conclusions, resisting the emotional propaganda that so many WWII films ironically default to. Instead, Guédiguain’s film tackles the complexity of this paradox, ultimately stating the problem of the resistance’s own structural similarity to military organization without pretending to solve the problem with soliloquies and heartbreaking montage. Certainly the cast should get credit here: Simon Abkarian and Virginie Ledoyen deserve especial attention as the film’s central couple, however Grégoire Leprince-Ringuet’s understated performance as a young resistance member is surely one of the most memorable, in its quiet encapsulation of youth on the brink of tottering into an adult realization of the resistance’s devastating demands. A Cannes Official Selection, this film earns its recognition, and proves once and for all that cinema can tell these stories without biting its own tongue.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram