The last game Elizabeth LaPensée designed got her in hot water with certain American senators; they accused her of training eco-terrorists; and she was audited by the government.

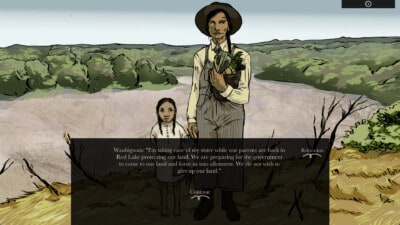

Now, she’s designed When Rivers Were Trails, a choose-your-own adventure game about Indigenous nations dealing with the impacts of Allotments Acts in the 1890s. The winner of the Adaptation Award at IndieCade 2019, When Rivers Were Trails was developed in collaboration with the Indian Land Tenure Foundation and Michigan State University’s Games for Entertainment and Learning Lab thanks to support from the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians and contributions from over thirty Indigenous writers, artists, and musicians. It will be making its debut at the iNDigital Space in imagineNATIVE this year.

“Allotments were a way of saying; we’re going to divide this land and allot some to native people; then the surplus (conveniently) can be sold or given away,” LaPensée explains. “They created these small plots and use what was referred to as a checkerboard pattern. It’s a way to say; we’re giving land to native people; but effectively what they were doing is splitting everyone up, and dividing up the land.”

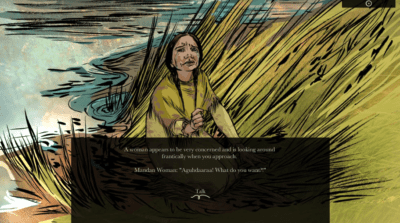

Some communities were able to fight back and hold on to their land. But for others, it was simply taken. That’s where When Rivers Were Trails begins. The project involved pulling together more than 20 Indigenous writers who contributed the true stories of what was happening in the late 1800s, gleaned from elders, storytellers and community members.

“There are stories in this game that cannot be read about, because they are not written anywhere,” she says. “At one point if you take a certain path, you come across an eerie abandoned railroad area. Nothing in the game is explicitly written there, but I had brought in a Chinese game writer, Cat Wendt. She had been looking into her own family history, and why her family had left Montana; there was a lot of violence, they were banned from being able to own businesses, or make any kind of sales or have any kind of self-sufficiency.”

As they were talking about the land and the stories, the Blackfoot writer Sterling HolyWhiteMountain recognized the place where they were looking at; something had happened there generations ago. “A whole ditch was dug, and Chinese people were brought out there who had been working on the railroad. And when all the work had been done, they brought them to that place, and they lined them up and they shot them all. And then they just put them in the ditch. This place has no markers. This place is not written about. It’s a story the Blackfoot people know and tell. That story was able to be passed on to Cat Wendt who had never heard about that before. But it gave a lot of perspective and understanding about why it was her family wanted to flee from Montana, and why it was the Chinese people came to California for some amount of safety, it really was a matter of life and death.”

In designing the game itself, LaPensée was focused on portraying the land accurately; with no state lines, and no state names. You have to navigate through the story in relation to the land, and in relation to the water systems. Her research relied on maps from the 1890s, which were focused on railroads. “These maps were meant to promote railroads; how we were going to have better expansion and things were going to move faster and here now we have access to these different cities, and look at all this growth. That land was named incorrectly by non-Indigenous people. On one map, it says ‘The Great Sioux Reservation: Opened for settlement‘ across one big swath.”

“Basically, what they were saying was come take the land! You can understand better why a place like Standing Rock has so much trauma embedded in it, in part because a lot of what happened there was so absolutely devastating; just come come grab it. It was a well-advertised free-for-all.”

Elizabeth LaPensée finds that video games are ideal for conveying the stories of Indigenous people. “They are dynamic spaces of expression, which are equivalent to storytelling,” she says. “In storytelling, we’re intended to really visualize and bring about that experience, and we can also revisit a story or a storytelling experience throughout our lives, and it can change meaning, or it can change in regards to what we are seeing or hearing. And it is also understood to be a collaborative experience. It is not a top-down experience where the storyteller is like putting upon a person their version of a story, but rather when a storyteller speaks, it is understood to be co-created between the listener, and the storyteller. The games are very much the same way.”

They’ve introduced the game to 400,000 students across the U.S., and have discovered that this medium is ideal for getting students to empathize. “They start to identify an impact; they understand that people were displaced, they had their rights taken from them. Then they become more invested into the curriculum, and the formal education that happens in the classroom.”

While the Allotment Acts took place more than a century ago, LaPensée stresses that the same things are happening across North America. “Reservation lands are still under threat,” she says. “When this game came together, there were conversations happening about our current president dividing up land again, underneath another act — under the guise of individuality, entrepreneurship, independence — using all the same tricks and lies, only today.”

Part of her hope is that there will be a generation who plays this game, and that they will learn from it. “[They’ll learn] what happens when land gets divided up into plots. And that people will look into policy, and that there will be more native lawyers and those on the ground level who can look into how can we can actually retain our land and our rights.”

“In terms of our social media networks, we are mobilized; we can communicate quickly across communities and garner support for one another. There’s been a lot of growth there. Is there more support in terms of honoring treaties? Absolutely not. But more and more nations are asserting their sovereignty.”

imagineNATIVE starts this week; check out When Rivers Were Trails at iNDigital space here.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram