Bookmarked is a new series in which She Does the City contributor, Erica Ruth Kelly, speaks to some of our favourite women about the books and stories that shaped them.

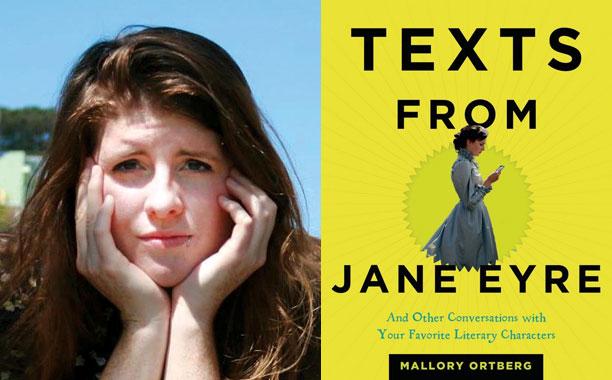

Mallory Ortberg keeps stifling her laughs while we’re on the phone. The New York Times‘ bestselling author of Texts from Jane Eyre and co-founder of the much beloved, recently closed feminist blog, The Toast, is leafing through sections of The Benchley Roundup (Harper, 1954).

This collection by American humourist Robert Benchley contains essays previously published in Vanity Fair, Life and The New Yorker, with titles like “The Menace of Buttered Toast,” “The Tortures of Week-end Visiting,” “What – No Budapest?” and “Football Rules or Whatever They Are.” Ortberg’s smile is nearly audible as she reads parts of “What – No Budapest?” out loud – an essay in which the speaker staunchly defends his ignorant view that Budapest does not actually exist.

“Robert Benchley is one of the funniest writers who ever came down the pike,” she says. “I think he should be rediscovered by more people.”

Ortberg and I talk about the collection, her parents, satire, and how she loved Benchley’s work for the way he both acknowledged and laughed at his own pain. “In a way, I prefer someone who’s a little willing to puncture their own balloon of self-seriousness.”

Erica Ruth Kelly: How did you first hear about The Benchley Roundup? How old were you?

Mallory Ortberg: Probably about ten years old. My parents both loved Robert Benchley and grew up reading him. He was a member of the Algonquin Round Table and Dorothy Parker was sort of there to make him look together, you know? He was the one who was often taking her home and being like, “Dorothy, when are you going to stop drinking and marrying gay men” and she was like, “NEVER!”

My parents both grew up reading him because he wrote a lot in the twenties and thirties, so by the time they were growing up in the fifties and sixties, a lot of his stuff was anthologized. When they were dating, and then again when they were early married, they would read his essays to each other. We always had Benchley in the house growing up. When Dad does readings, he does voices in a really wonderful way and I remember just cracking up. There’s this one essay [Benchley] wrote called “What, No Budapest?” and every time I hear it I laugh and I can hear my dad saying it in my mind.

What it is that you loved about it?

I really loved the light comic touch that had this sort of affected, devil-may-care rakishness, but the content would totally belie that tone. [Benchley] would be writing in the style of “I’m a man about town. I know what I’m talking about,” and then he would immediately undercut that by making himself look quite foolish. And that style of comedy always makes me laugh. The way he did it just felt breezy and artfully effortless.

What kind of impression did it leave on you? How does it connect with your worldview or your own writing as a satirist?

There are so many roots of my own writing in there. It’s just that kind of smart person doing something purposefully dumb, making an outrageous claim that’s clearly untrue and doubling down when someone tries to challenge it.

Could you draw a connection between Benchley Roundup and Texts from Jane Eyre?

It’s a collection of short pieces that are jokes, many of which are about literature and culture and sort of famous characters. It’s definitely not like, “First comes The Benchley Roundup and then a direct descendant is Jane Eyre,” but there’s absolutely a real connection.

I find it very encouraging that you still find it funny after all this time. I’m thinking back to this old episode of Cracked’s podcast where they were talking about how humour evolves…

Right, humour doesn’t always age terrifically.

It just doesn’t happen very often where you can look back at something and recognize it as objectively funny but still personally find it funny, too. It’s exciting this book still does that, because there’s nothing funnier than someone who looks completely ridiculous but has no idea.

Absolutely. There’s something really wonderful about reading humour that’s close to a hundred years old and feeling pretty connected to a lot of it. There are certainly moments where he is clearly a writer of his time. I’m sure there’s some stuff in there that I would read now and feel like, well, “I’m sure glad we don’t order our society around these ideas so much.” But, no, there’s lot of it that feels very much like something you could read right now, like this piece called “Read and Eat:” “I have always secretly admired people who can read a newspaper while eating. This speaks coordination, dexterity, and automatic digestion. None of which attributes I seem to possess. It also gives one an air of being a man of affairs. I long ago abandoned the attempt to look like a man of affairs. I even find it difficult, some mornings, to look like a man.” It feels deceptively light and very modern.

Follow Erica @ericaruthkelly

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram