As a writer, I am always looking for ways to put language around significant events or moments that shake us. In the summer of 2021, in the middle of the pandemic, words felt hard to come by, in much the same way most things seemed more difficult, including going to the grocery store or taking the kids to the playground.

In the swell of these hard things and the devastating headlines that flooded all of us, I did manage to find a more uplifting story. It centred on a woman leading a troop of residents in Thorncliffe Park to grow their own food, in a secret garden behind a 20-storey tower, beside a sprawl of asphalt and parked cars.

Ten percent of Thorncliffe Park’s population is Afghan. I know the area well and whenever I’m there, I find myself hunting for the smells and sounds that take me back to my Afghan upbringing.

That summer, the Taliban marched back into Kabul. Many of us can remember news clips of one of the last Western planes leaving the country’s capital with desperate Afghans running alongside and hanging onto the aircraft as it took off.

My own family fled Afghanistan in the 1980s and 90s. Yet events of that summer reopened old wounds and formed, as my aunt said, “a new and deeper sense of loss.” My Afghan family was also grieving the death of our matriarch, my grandmother, who, because of COVID, was forced to die alone, and did after saying goodbye to her children on an iPad.

I could sense that my writing self was more frightened than usual to come forward that summer. On a whim, I decided to reach out to the woman who created and ran the gardens in Thorncliffe Park. Michelle Delaney was her name, and I quickly discovered she was someone who spoke quickly but intentionally, who had big ideas but also a grounded conviction in the simple acts of being together, paying closer attention and making things to share and give away.

“Gardening creates connection,” she said while taking me on a tour of the garden’s fruit trees, which are dispersed around a series of apartment towers. “It draws us closer to seasons and cycles in life. We grow more curious about why things are, and we start to really understand how everything is connected. Really, gardening is about nurturing growth and tending to it every day, physically and mentally.”

While we toured the gardens, Delaney introduced me to Patricia, a resident who also worked in Long-Term Care. “I had always admired the gardens,” Patricia explained to me. “This year, I felt called to get involved. I was nervous of course, but welcoming this new space into my life has led me to my own inner garden, and in healing ways.”

Soon, I was obsessed with the space and its “urban farmers.” Delaney’s drive, vision and sense of mission were magnetic. “We’re not just gardening for our well-being and to create community, we’re also addressing real food security issues in our neighbourhood, and with nutritious food.” The garden grows over 1,500 pounds of food a year for residents.

Even so, I was intimated by the world Delaney created. I’m not a comfortable gardener. As a writer, I’m more at ease with building worlds with language that grows something inside me.

It soon became evident, though, that gardening and writing were siblings, or similar ways to connect and expand during times of fear and uncertainty, times when we want to hide out in our bunkers.

As it turns out, my sense was right. Advancements in technology and research can now show how art and gardening are inner workouts that generate cognitive and physical changes.

In the New York Times Bestseller “Your Brain on Art,” authors Ivy Ross and Sue Magsamen spell out what happens physiologically and chemically when we create. They highlight studies that show how, when we operate in the realm of artmaking, gardening, listening to music, and the like, we increase the brain’s plasticity. We grow an ability to adapt, to trust, to be comfortable with uncertainty, to stay open to our emotions, to think differently.

At some point that summer, I ask: Would the Thorncliffe Park gardeners want to explore writing and artmaking in the garden? There were those who were unsure about taking that risk, but others told me they felt a spark had been lit by the garden and that they were eager to create in a more personal way.

Delaney joined every workshop. “I couldn’t get over the idea of writing not to communicate what I already understand, but writing in order to understand,” she said at the end of our first session. “It opened my mind.”

Since that summer, the garden’s creative pulse has grown. Delaney and I have partnered with Story Planet, a non-profit whose mission is to amplify the voices of young people in Toronto’s equity-seeking communities, and together, we offer art and story workshops in the gardens to all ages for free.

Last month, a group of teens asked for more writing workshops that explored voice and non-linear forms. “The beginning-middle-end structure of writing is so limiting,” one young woman said. And I agreed. “Creativity should be defined by its expansiveness, how it helps us blossom into bigger expressions of ourselves.”

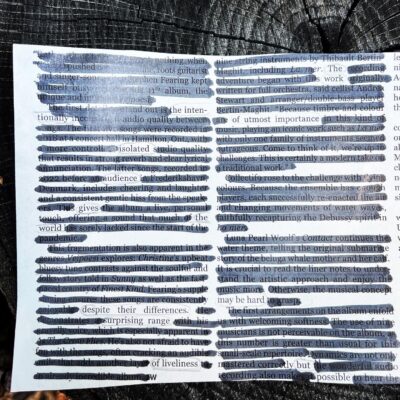

In my first session with the teen group, one girl shared a blackout poem, where inside a newspaper clipping she uncovered the words “The work of utmost importance may be hard but possible,” and other phrases she saw could be weaved together to articulate something meaningful to her.

Another teen explained how she came to Canada a few years ago and has found freedom in expressing herself that was forbidden in her home country. “It is my dream to share my art, my voice,” she said to me. “And I get that opportunity here.”

My own search for a wider lens and voice on Afghanistan continues. At times, the language comes and I can sense an unscrambling of dense, confusing matter. But when the writing feels hard, I’m pretty grateful for Delaney’s gardens and the world of the Thorncliffe Park urban farmers. Whenever we gather to make art in plein-air, something unique and grounding comes forward.

Find Thorncliffe Park Urban Farmers at Canada Helps to donate to the garden and its community work.

Nadia Shahbaz is a writer and former radio news producer of Afghan and Italian heritage. Her work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and illuminated on buildings in New York City. She is currently working on a novel on Facism and her Sicilian family. You can follow her work in the gardens and elsewhere on Instagram @nadiashahbaz_writer.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram