Artist Ai Wei Wei’s studio/home in China is overrun with cats and dogs. Over forty of them in total, he tells the cameras in director-producer-camerawoman Alison Klayman’s first film effort, AI WEI WEI: NEVER SORRY, which opens on July 27th.

One of the cats has learned to open doors, leaping into the air to knock the handle down with its paws, and then prying the door open with its face. It would appear that living in Wei Wei’s home might be what gave this super-cat its powers of adaptability. The artist has been detained for 81 days by the government, punched in the face by Chengdu police, and is currently banned from publishing on his blog, which he used to personally update upwards of twice per day. Aside from his persistence in the face of governmental and legal adversity, Wei Wei has also adapted quickly to emerging technologies—a prolific tweeter and photo-blogger, in the years between 2010 and 2012 he produced between 10 and 15 documentaries and distributed them online.

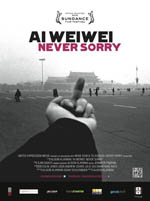

While Wei Wei is not a stranger to the camera (some of his most famous works are pictures he has taken of himself giving the middle finger to various world landmarks including Tiananmen Square), usually it is he who is in charge of the completed result. In this instance, journalist Alison Klayman, who gained “unprecedented access” to Wei Wei during four years in China as a freelance journalist, takes the reigns, interviewing his wife, mother, brother, fans, baby-mama and other journalists as he fights to file a lawsuit against the police officers who detained Wei Wei from testifying at his friend Liu Xiaobo’s trial for subversion of the power of the state. Xiaobo was sentenced to eleven years in prison, and Wei Wei was beaten so badly he had to get surgery to calm the swelling in his brain.

Though there are some sobering revelations about the state of free speech in China and other areas of the world, the documentary manages to maintain a light-hearted tone consistent with Wei Wei’s approach to art, freedom and communication. When the government installed surveillance cameras outside his home, Wei Wei made beautiful marble replicas, turning their act of intimidation into an act of art. After being punched repeatedly in the head, he took a selfie with his phone and tweeted a photo of himself and his uniformed assailant to the world, sharing a story of injustice and turning his injury into a call to action. While Wei Wei is currently prohibited from participating in social media exchanges and travel outside of China, the film offers a window (a cat door?) into the life of the artist and communicator’s present status and hopes for the future.

~ Monica Heisey

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram