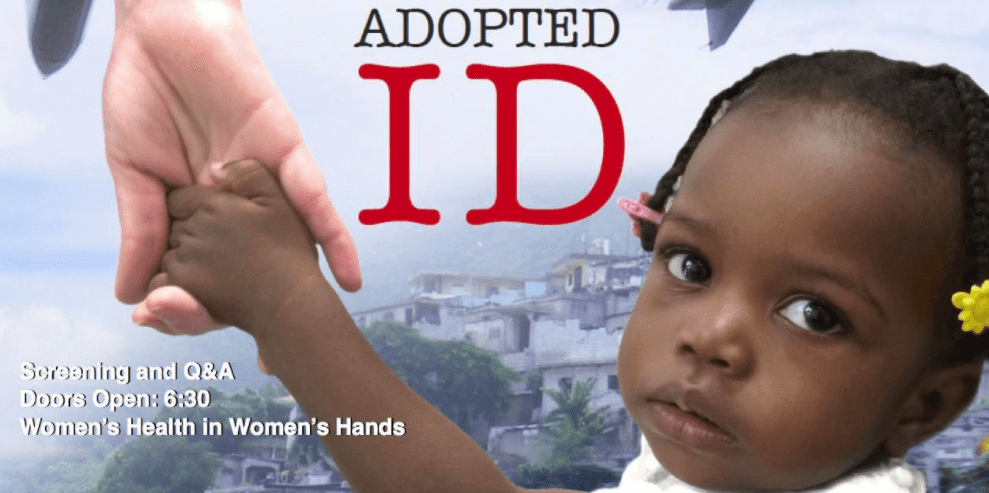

Tonight, Sonia Godding-Togobo’s documentary Adopted ID is screening at Women’s Health in Women’s Hands.

Adopted ID uncovers Judith Craig Morency’s extraordinary journey as she bravely returns to Haiti to find her birth parents. From the poverty-stricken families who’ve given up a child, to the foreign families looking to adopt one, these disparate worlds collide amid her quest to solve the puzzle of her past. With the insights and sounds of pre-earthquake Haiti as a backdrop, these intersecting lives provide a rare and intimate insight into the conditions surrounding transracial adoption.

Judith Craig Morency is a trans-racial, trans-national, foundling adoptee from Haiti who was adopted into a white Canadian family in the early 1980s. She is also the subject of Adopted ID. We spoke with Judith this week to find out more about her journey and the resources that can help other adoptees.

SDTC: What’s your earliest childhood memory?

JCM: My earliest memory is playing with my big sister in our yard in America riding our Big Wheel. Another child came up to us asking who I was. My sister said, “That’s my sister.” The boy refuted this, and I remember my sister saying over and over, “That IS my sister, she’s adopted, she’s my sister.” She claimed me and stood up for me, I love that.

In an article you wrote for Huffington Post, you talk about the importance that adoptee parents “adopt the whole child.” Can you expand on what you mean?

Adopting your whole child means accepting your child’s birth history, birth family, culture, ethnicity ALL of the elements that make up your child; we are multidimensional even as babies. Too often well-intentioned families adopt children and focus on “claiming” them as part of their family and wanting to give them a sense of belonging, which in theory is great. The challenge comes when you claim them so hard that you disregard their beginnings and you believe their life started when they joined your family. It’s simply not true and it can be very dangerous and dismissive of your child’s history.

Some may say, “But their history was traumatic and painful,” and while that is often the case, it doesn’t mean they aren’t mourning the loss of their birth family. Respect needs to be shown that your child was born to someone else and without that person you wouldn’t have your child. Adopted children are often told to forget their past, their birth family, their history, and be grateful they were “saved” and given this new, better life. It doesn’t work like that; children need to be able to mourn the loss that they suffered and being able to do that with you as their parent will enable a closer relationship to form.

Regarding your child’s culture and ethnicity, I challenge parents: if you can’t or won’t accept that your child is different from you, why are you trans-racially adopting? That cute black or Asian baby will grow up into a black or Asian adult and will need to know how to navigate the world as a person of colour. Celebrate the difference in your family; don’t try to pretend it doesn’t exist. The world is not colour blind and you can’t be either.

As a black child in a white family, did you ever feel as though you didn’t belong? Or that you didn’t fit in the community you grew up in?

Yes, all the time! Not so much from my immediate family; it came more from outsiders. People look, stare, comment, are insensitive, rude and racist. I’ve experienced all of that and then some, and it is very hard to feel like you belong when it’s always being pointed out by others that you don’t look the same, that you are different. As I said above, difference should be celebrated but it also can be very painful and awkward when it’s always being brought up and your existence within your family is challenged.

Up until my second or third year of university, I didn’t feel comfortable in a room full of black people. That, to me, is very sad, but it was my reality. While I did grow up in a multi-ethnic community, our church youth group was predominantly white and that’s where I spent most of my time and had my closest friends. In school I was part of the “mixed group,” which was great, but I had horrible anxiety when I had to enter a space with all black youth. Whether it was a Black History Month event my mom made me attend, or walking past the “black kids corner” in school, I just felt like I couldn’t relate to them and was being judged because they all knew my family dynamic.

How did your parents help you nurture your culture and history? Understand it and appreciate it?

My parents focused on trying to educate my brother and I on potential experiences we may face where we could be stereotyped. We had some black art and books in our home and they tried to promote our sense of black beauty. They took care of our hair; my mother learned to cornrow and did it as often as possible with four other children to care for. I remember watching Roots with my mom when I was a teenager and cutting out articles about Haiti from the newspaper. Sadly, most of those articles were very negative so I didn’t gain a positive perspective about Haiti until I travelled there myself in 2007. My parents truly tried, but I lost out on really understanding and embracing my Haitian black culture and that is a significant loss I experienced through my adoption. I’ve been on a steep learning curve the past fifteen years to educate myself around my Haitian culture.

A pivotal moment for me was also having a very close relationship with a black family that lived down the street from us when we returned to Toronto. Once I spent a few weeks with them I started to accept my self more. Prior to this, I wanted to look like my family: white skin, long blond hair, pointed nose, the whole image I saw reflected in front of me. My parents were sensitive that we needed to be raised in a diverse community and turned down a job opportunity that would have meant we would have returned to a very white neighbourhood. I appreciate that they took my brother and my needs into consideration in this way.

What’s your top advice to parents who are in the process of adopting a child from another culture?

Walk a day (or more) in your child’s shoes. Take yourself to the community that your child is coming from and immerse yourself in it. Read about trans-racial adoptees’ experiences and be open to hearing what they are saying. It’s not about attacking you; it’s about trying to ensure your child has a well-rounded experience. Befriend people of all cultures but especially your child’s as naturally as you can. Be sensitive to where you live and the people in your life. You may need to cut ties with family and friends who are racist. Be aware your child will have experiences that you have NEVER had; LISTEN to them, empathize and equip them. Don’t be afraid to ask for help from others within the community. It doesn’t mean you’ve failed; it means you know raising your child takes a village, and that village needs to include people your child can relate to and see themselves reflected in.

You are still on a quest to find your birth parents. Where are you at with that right now? What feelings do you have about finding them?

I’ve turned to DNA Ancestry testing sites to search for my birth family and I’m so happy I did as I’ve been successful in finding my paternal family! Unfortunately, my birth father is deceased and I’m still very much mourning that loss, but I’m so excited that I have seven siblings from him and I’m beginning to develop relationships with them. It’s been incredible! They’ve been so warm and welcoming and loving. I’m planning a trip to meet with some of them in December, which is truly a dream come true. I also have an aunty, uncle, eight first cousins, nieces and nephews, so there are a lot of people to get to know.

Regarding my maternal family, I’m even more determined now than ever to find them and I’m hoping that my birth mother is still alive and wants to meet me. I need my story to reach her and for her to come forward. I don’t want to miss meeting her like I have my birth father. I want her to know that I’m not angry – just incredibly curious.

What was the best part about being in this film?

Having my journey filmed had its challenges, but I’m so happy that I have a record of this incredible experience and that I have this tool to search for my family and share my story with others. I’m particularly passionate about adoptees’ voices being heard. I’m thankful to Sonia Godding-Togobo for giving me the space to share my story and I hope it assists other adoptees, birth parents, adoptive parents and adoption professionals.

Anything else you’d like to share?

Adoption is complex; it involves losses, gains, trauma, multiple families, searches, reunions, culture, ethnicity, racism, search for identity and belonging. Adult adoptees don’t have a lot of support networks to manage all of these intricacies and because of that, sadly we see a higher number of adult adoptees with mental health issues and committing suicide. We need to work harder to combat this.

One method of doing this is through our adoptee communities: myself and fellow adoptee and psychotherapist Sheilagh O’Sullivan are co-facilitating a new group for adult adoptees. It’s the Adult Adoptee Network and we are going to be meeting several times per year. I’m really excited about this group as it’s something I recognized was needed twelve years ago before I left Toronto for the UK; now that I’m back I’m glad to be apart of it. It’s open for all adult adoptees. They can join us on Facebook (search Adult Adoptee Network) or email us at adopteenetwork@gmail.com. Our first session is January 20, 2018.

Adopted ID is screening tonight at Women’s Health in Women’s Hands (2 Carlton St Suite 500) at 6:30 PM. Tickets are $10. Get them here.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram