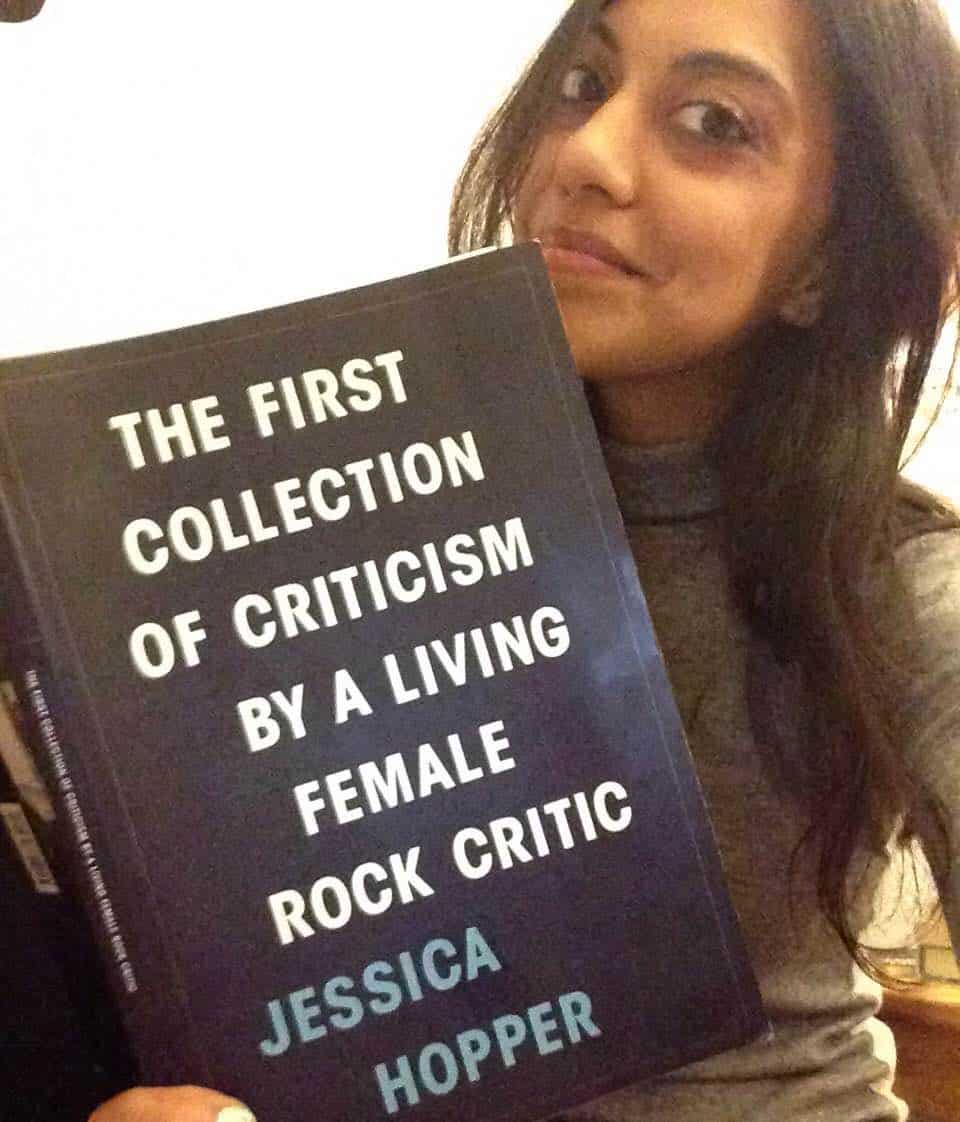

After a reading and Q&A at Type Books on Queen West late last month, Jessica Hopper signed my copy of her latest, The First Collection of Criticism by a Living Female Rock Critic, as follows:

“yours in misandry, jessica hopper.” (Well, she also scribbled in a little heart before the j. D’awww!)

I am a bona fide fan of Hopper’s. Recently retired from the editor’s post at Pitchfork magazine, her new collection of essays is pretty much what its title suggests — the first book of critical music writing to be published by a woman in the mainstream.

In the book you’ll find out Chance the Rapper’s favourite library branch and what Lady Gaga wears to the airport — but also how posing as a grunge-head spurred Hopper’s musical awakening, and more on her complicated relationship with an industry that tends to treat women as little more than video hoes or muses to be harvested. Hopper is therefore an attractive heroine for any woman who has loved (anything) and felt like that love was less worthy or not the right kind.

She is punk as fuck, has a stellar career, inimitable taste in tunes, and is emphatic enough to turn an interview with Bjork into an impromptu sob session. She manages all this from Chicago, where she resides with her husband and two kids. That’s essentially living and breathing evidence that, yes, we women sure can have it all! Here are three other lessons I learned from Jessica Hopper, the patron saint of fangirldom.

“My teen-girl soul mattered”

When she was still a teenager, Hopper started a Riot Grrrl fanzine to plant her own flag among the sea of dudes already doing something similar. (And the rest is music journalism history.)

Staking your claim isn’t a challenge unique to women who work in music or publishing; so many of us rely on creative outlets and end up clamouring for validation. And it would seem that by simply being born with a penis entitles you to opportunity, or endows you with boundless reputation and credibility and importance. If you’re a woman with an opinion, you are sometimes made to feel like you are taking up too much space.

So when Hopper wrote that her “teen-girl soul mattered,” it bolstered my own self-worth and stoked my fiery insides. It was almost as if, from a prick of my thumb, a flame would emerge where there should be blood. Her yearning is inspiring, infectious, and evokes an all-too familiar feeling. Now I can put a name to that fire and give it purposeful release.

It’s okay to love openly, grossly, unconditionally, foolishly

As a fan, there is no right or wrong way to love a band. (I’m looking at you, hysterical tweens climbing into the front row at a One Direction concert).

A couple summers ago, I was lucky to have a steady gig writing about the local Toronto music scene. My editor at the time jokingly referred to me as a “Beatles fangirl” because I liked every band I happened to write about. Sure, his comment may have been tongue-in-cheek, but it still stung. What was wrong with liking a record so much? Did I really have to find something negative or critical to say, just for the sake of it?

The answer is, duh, no. Even when I discuss music with a (certain type of) man, there is no way he’ll believe I love a musician for his poetry or performance, but for some silly school-girl crush. Instead, as a girl, the appropriate fan etiquette is to throw panties on stage and practice doodling a new signature with his last name in place of mine.

Not surprisingly, Hopper’s experiences in the music biz are way amplified, but relatable. She is irresistibly earnest — unapologetically and passionately. It’s no wonder I can feel the very chains unlocking my heart whenever I read her words.

“We deserve better songs than any boy will ever write about us”

This goes beyond any one album. Women are constantly making exceptions and negotiating boundaries for all the fun things in life — art and books and music and film. We forgive sexist and racist passages in the name of literary and lyrical quality, or dismiss any such work as historical or based on antiquated practice. I mean, Tom Wolfe is one of my best-loved authors but he is also, by virtue of his writing, kind of a bigot. I could say the same for Action Bronson.

It would be unfair and naive to shield ourselves completely from misogynistic art forms. Actually, to embrace them is just fine — the canons of art and feminism are hardly perfect.

Here’s the thing: I like to create, too. We all have a story to tell, and sometimes, oftentimes, a woman’s story is the one we connect with. So why not her voice? Or Hopper’s or yours or mine? If it is indeed a man’s world, I’d prefer to make it my own.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram