I have read 120 history books and articles since September. My peers and I purposely try not to keep track of the number of books, though, because having finally stopped to count, I am now gently vomiting onto my laptop and laptop accessories (my lap and my top—keep up).

120 is a terrifying number for two reasons: I have to read an almost-equivalent number of texts by mid-summer, and when the overall count finally reaches 200, I will sit eleven hours of exams so that I can move on to the stage of my doctorate program where I actually get to research a thing.

Basically, the past eight months have been an exercise in not losing my mind, or more importantly, my focus. I have been so absorbed in my books that I’ve started Instagramming pages (my history friends “like” my photos, and my non-school Instagram friends enter REM sleep, I think). I’ve also been eating A LOT of chocolate, Wheat Thins and those instant Thai noodles that come with a weird oil packet.

Friends working in journalism, design, computer science and engineering are often struck with huge, looming deadlines that require hours of overtime and weeks of sleep deprivation. So I’m really trying to frame this gigantic reading list as just another professional requirement towards a greater professional end.

Every humanities PhD program has slightly different requirements for comprehensive (comps) exams. Some students may study for and write their comps in the second year. There may not be a written component, or there may be several variations to the written component. If you do a PhD in the United Kingdom in History, for instance, you won’t even be required to do comps. Comprehensive exams are an inevitable rite of passage in North America, though. If you are considering a doctorate in the humanities, they are just part of the package.

So, every two or three weeks I meet with each of my three advisors to discuss a new stack of books, in an informal-oral-test-like setting, slowly working through booklists for three different fields in which I aim to claim “expertise.”

Then, this summer, I will sit nine hours of written exams. Following this, I will sit in a room with three of the smartest, most professionally accomplished academics I know—Canadian Research Chairs, past and present department chairs, published, multi-lingual, inspiring individuals—and I will try to convince them that I’m knowledgeable, critical, and well-read-enough to consider joining their club: the doctor club.

When I successfully convince them, in each of my three selected fields, that I truly understand the literature, the debates, the geography, and the history well enough to teach the subjects in question, I will be set free on the world. I will unleash on academia a fiery hellstorm of innovative thought, vastly original archival research and publishable writing. Scholars will sing my name in hallowed halls. Jobs offers will spill out of my mailbox. I might wear a crown.

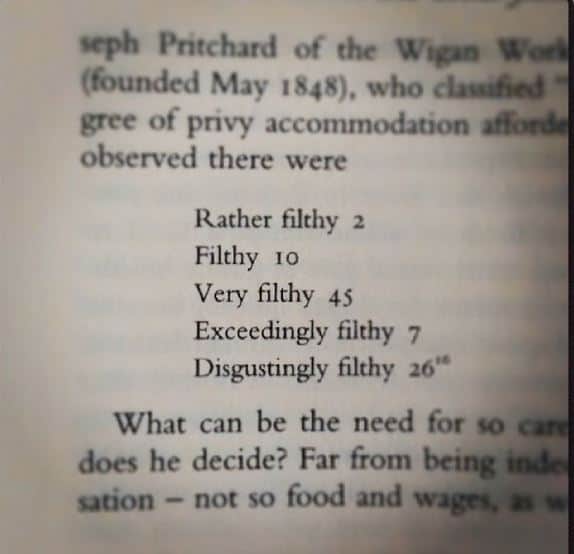

At least this is what I tell myself when I’m reading the fifth consecutive book in two days about state policy and sanitary laws in nineteenth century England. There were no sewer systems. That sounds awful, and from what I’ve read, it was. Can I have my doctorate now?

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram