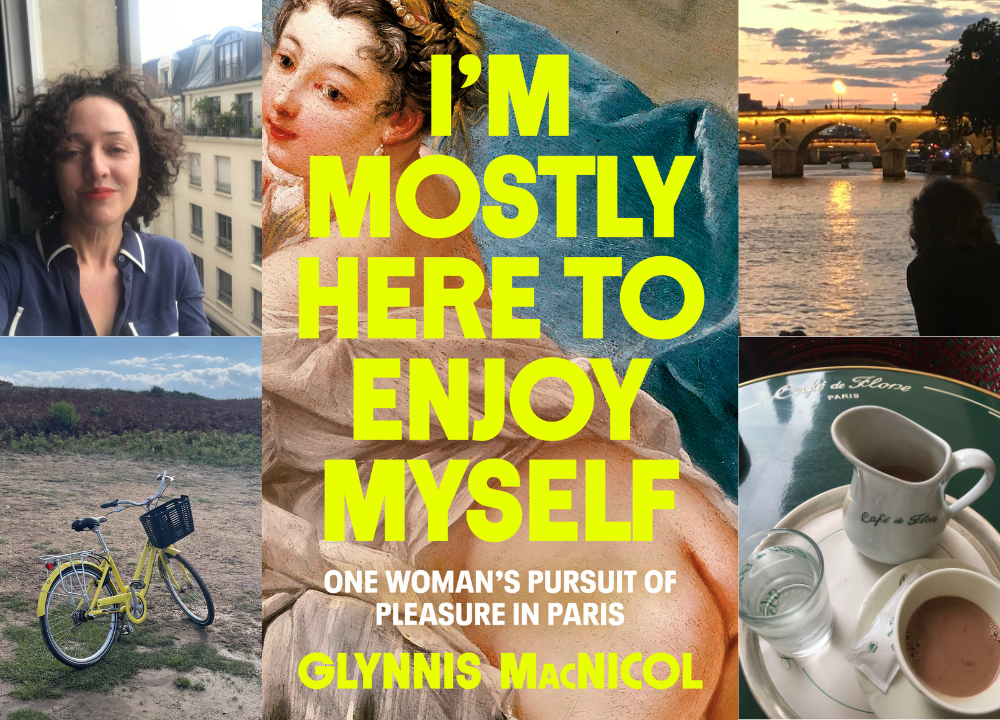

In her decadent memoir, I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself, Glynnis MacNicol chronicles her search for radical enjoyment that leads to a transformative year of living in Paris.

When the pandemic hit, MacNicol was a single woman in her 40s with no children, isolated for months in her tiny Manhattan apartment. In dire need of a change, MacNicol jumped on a chance to sublet her friend’s apartment in Paris. What followed was a joyful, pleasurable journey full of friendship, sex, and food.

As the memoir’s description details.“There is dancing on the Seine; a plethora of gooey cheese; midnight bike rides through empty Paris; handsome men; afternoons wandering through the empty Louvre; nighttime swimming in the ocean off a French island. And yes, plenty of nudity.”

Through intimate insights in the vein of Nora Ephron, MacNicol strives to discover what pleasure and fulfillment look like for her, especially in a world that tells women pleasure isn’t possible, or a priority.

As you bask in the final weeks of summer, this is a perfect book to indulge in, and perhaps prompt a reflection on what pleasure means to you. And if the Olympics (especially the showstopping Opening Ceremony) have reignited your love for Paris, immersing yourself in MacNicol’s adventures through the city will be a delightful escape.

Please enjoy the following excerpt from Chapter 3 of I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself, titled: Prized Control, Yearned After Momentum.

Adapted from I’M MOSTLY HERE TO ENJOY MYSELF by Glynnis MacNicol, published by Penguin Life, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Glynnis MacNicol.

I’m overcome with a sense of wonder. If I had to turn around right now and go home, I would still be satisfied with this brief excursion. I came, I saw, I touched. It’s still here.

But I don’t have to leave.

Instead, I drag the monstrosity containing all the me’s into the bedroom and throw it open.

Now that I can take in its contents, my suitcase strikes me as extremely reasonable.

I’ve brought five vintage caftans; two dresses; two jumpsuits, one of which is vintage; six T‑shirts; three tank tops; four blouses; three pairs of pants; three black leggings; two pairs of jeans; two long-sleeved shirts; one sweater; a vintage Issey Miyake wind coat in camel; a proper raincoat in leopard that I bought at Merci two years ago when I got caught in a rainstorm; a black blazer from H& M that is the exact one Natasha Lyonne wears in Russian Doll; two silk scarves; one cashmere scarf; my running clothes; three swimsuits, one the closest approximation I could find to the one Romy Schneider wears in La Piscine, which I’d seen six times at Film Forum before leaving New York. In the insert are fifteen pairs of underwear, unnecessary as there is a washing machine in the apartment; five pairs of socks; my yoga shorts and tank top; and a trucker cap in camouflage with the word JAWS written in silver lettering across it.

In The White Album, Joan Didion famously wrote down her packing list, radical at the time—Tampax!— and revealing in its intimacy and simplicity. As a storytelling device, it was admirable in what it told the reader about the writer, about her life, and about what it meant to be a woman in the world, without seeming to say much.

Didion wrote the list in 1979, but it has gained new life in the last ten years, surpassing, at times, the popularity of her “Goodbye to All That” essay about leaving New York, which has seemingly been redone by every writer leaving the city ever since.

Didion’s packing list, however, is perfectly suited to our social media times, which strives to reduce all life to small performances of intimacy. And at the same time add credence to the daily activities of women. There is a similar vibe in Nora Ephron’s essay “On Maintenance,” from the collection I Feel Bad About My Neck. In it, Ephron writes at length about upkeep: “There’s a reason why forty, fifty, and sixty don’t look the way they used to, and it’s not because of feminism, or better living through exercise. It’s because of hair dye.” Between Ephron and Didion an entire corner of the internet finds its source. Whenever someone needs a reliable traffic generator for their website or follow count, they can turn to Didion’s list and lean on her “bag with: shampoo, toothbrush and paste, Basis soap, razor, deodorant, aspirin, prescriptions, Tampax, face cream, powder, baby oil.” So easy. So succinct! So serious. So worthy. It gives gravitas to minutiae. So much of women’s lives are considered minutiae, the appeal in this sense is understandable.

But if you go back and read the full essay, it goes beyond the list. Didion spends the following three hundred– odd words or so telling the reader what to notice. “Notice the deliberate anonymity,” she says. “Notice the mohair throw . . . for the motel room in which the air conditioning could not be turned off. . . . Notice the typewriter for the airport.” She wanted the reader to understand that that this was a list “made by someone who prized control, yearned after momentum, . . .determined to play her role as if she had the script, heard her cues, knew the narrative.”

Needless to say, judging by the explosion of clothes I have just sorted, I have none of these things. No script. No role.

Before we’d all been sent inside, I’d been in rooms with professionals, all women, who were extremely excited by the idea of adapting a memoir I’d written about turning forty, without children or a partner, for the screen. They’d read it and seen themselves in it—sometimes for the first time—and were thrilled. At times, a note of possessiveness crept in. As if I’d nailed the details so correctly, it felt as if I were telling their story. Which I came to realize was just one of the dangers of having so few stories about women outside the narrow ones our culture celebrates about marriage and motherhood—the perverse comfort it can bring by allowing you to think you are unique. When in fact, the uniqueness, if it can be called that, was simply in the telling, not the living. (And so much of the ability to tell was a function of where I lived, and who I knew, and, to paraphrase another internet favorite, the dresses I wore and where I went and what I did in them.)

The trick to getting this all on the screen was figuring out what the narrative was. “What is the problem she is trying to solve?” I was asked over and over. “What is the story?” “The narrative,” I would say, “is that there is no narrative.” “The story,” I would say, “is figuring out how to live when there was no role you could determine to play, or script to follow, or cues to hear.” You are all the dresses, and none.

This was an insurmountable problem in the end. I was left with the impression that the only female problems we understood women to have, and subsequently know how to solve, were love and children. Repeat. No one could figure out how to put another problem on the screen, because what other problem could there really be? What exactly was our heroine supposed to be working toward? Eve Babitz wrote that women are not prepared to have everything, “not when the ‘everything’ isn’t about living happily ever after with the prince (where even if it falls through and the prince runs away with the baby-sitter, there’s at least a precedent).”

We tried lots of different ideas: The inciting incident was that our heroine lost her job, but then what? She got another one? So what.

The inciting incident was that her boyfriend broke up with her and she had to figure out how to live alone. But then what? The inciting incident was that her rent was doubled, but then she moved in with her oldest friend in New York and her family (this is a true story), but then what? How were we supposed to know she was okay. That she was successful.

After the book came out, I would hear from some readers who wanted to know if I thought I was the first woman who had not been married or not had children. Which, lol (the only appropriate answer to that question is, truly, lol). They all seemed to have a happy aunt in the attic they wanted me to know about. Point me to the movie, the book, the show that depicts this, I wanted to say. The only example I could think of was the film An Unmarried Woman, starring Jill Clayburgh. In it, Clayburgh, who was thirty-three years old during filming, plays an—I think we are supposed to understand her as middle-aged—educated, presumably happily married woman who has a teenage daughter (sixteen or seventeen) and lives on a high floor in the East Sixties, with an extraordinary view of Second Avenue stretching all the way downtown. During the day she works at an art gallery on West Broadway in pre–Dean & DeLuca SoHo. One day her husband meets her for lunch and tells her he’s fallen in love and is leaving her for a younger woman. The rest of the film is about her falling apart and then putting her life back together. Including a passionate love affair with a bearded, tempestuous artist. When her husband comes begging for her back, she turns him away. She also spurns the artist’s offer for her to come live with him upstate. Instead, she decamps, by herself (her daughter is off to college), to a Brooklyn brownstone with a bay window and a backyard (I think—this movie is not available to stream anywhere so I must go off memory). The final shot is of her weaving her way up West Broadway trying to navigate her way while holding a huge painting given to her by her artist lover. It looks like a great sail on a ship she barely has control over as she sets out on her unmarried woman odyssey. Tell me the story of a complicated woman.

In the end there was no TV show. It’s easier to write divorce and widowhood it turns out. Only young women, with plenty of runway ahead to come to their senses, get to have messy challenges.

I close the suitcase and look around, still amazed it was all so heavy. Unpacked, it really doesn’t look like that much, let alone too much. It certainly doesn’t look like the weight of another body. It looks like the closet of a person with a full life. “Dress for the life you want” is a quote I also attribute to Diana Vreeland, though it sounds too basic for D.V. and is likely just something I read on Instagram. To me, all these now unpacked items simply say that I am ready for anything. To be anyone. How this will be accomplished is less clear to me. I’ve only thought as far ahead as getting here.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram