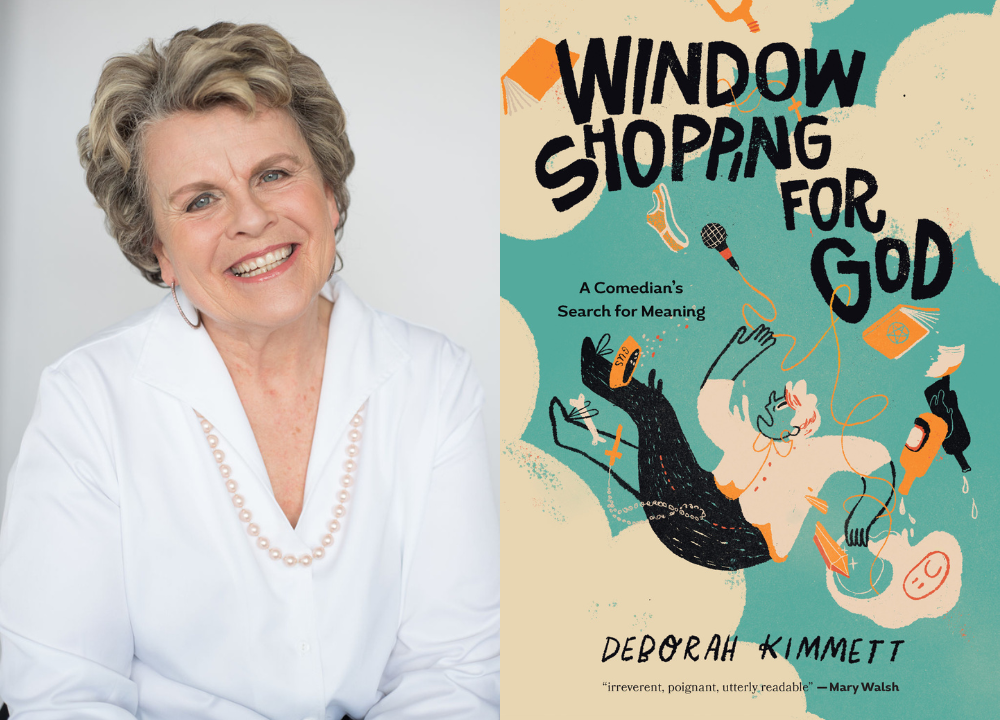

Window Shopping for God is the story of Canadian comedian Deborah Kimmett and her lifelong flip through the catalogue of beliefs—from a near-death experience as a teen, to her struggles with addiction and mental health, to her search for meaning as a woman in her 60s.

“The way I was raised you bought only from one store, Sears and when it came to religion you bought only from the Catholic Church. When I hit puberty it felt like I began outgrowing a lot of the ideas I had bought into. That’s when I began window shopping for a different kind of life. A different spirituality, and I went down many paths to find myself,” Kimmett writes.

Kimmett is a comedy trailblazer, with more than 17 years in the biz. She’s known for her appearances on CBC’s The Debaters, her regular spot on CBC’s Winnipeg Comedy Festival, CBC’s Laugh Out Loud, and her podcast Downward Facing Broad.

Window Shopping for God has received praise from the likes of Colin Mochrie, Tracy L. Rideout and Mary Walsh for its unflinching honesty, infused with Kimmett’s signature humour.

Kimmett says readers can expect “a page-turning book of stories of my uproariously funny and often touching spiritual journey of self-revelation and forgiveness.”

We’re pleased to share an excerpt from Kimmett’s memoir, out now!

Excerpted from Window Shopping for God: A Comedian’s Search for Meaning, by Deborah Kimmett. ©2024. Published by Douglas & McIntyre. Reprinted with permission of the publisher.

“DO YOU BELIEVE IN GOD?” The first day I met the man called Preacherman, I was sitting in front of the scone place at St. Clair and Christie as he preached the word of God. That’s if God was having a really bad day. He stood on his crate, impeccably groomed. He wore a beige cashmere coat—quite fancy for a street preacher—and a fedora with a black scarf under his hat to keep his head warm. Up on his crate, he loomed large to passersby.

Sitting there eating my scone, I had so many questions. What was the first day you decided to come out to the street and preach? Has your yelling converted one single person? And why do you never see a woman standing out here on soapboxes?

It was 2014, and I was glad to be back in the city, in the thick of things. I had my new old dog, Gus—a fourteen-year-old shih tzu with a severe underbite that made him look like Marlon Brando in The Godfather, “I’m gonna make him an offer he can’t refuse.”

I’d lived in both city and country settings for equal amounts of time. I grew up in a small town, moved to the big city, back to live on a small island near Kingston, and then returned to the city again.

I loved living in every one of those settings until the moment I didn’t. One morning, I’d wake up to a wind blowing in off the lake and I’d start building a case against the place and the people. Soon, I’d be gone again. I moved back to Toronto a few months after I found out my brother Kevin was sick. I had been perfectly happy living in the woods with twelve acres of forest behind me, the Cataraqui Trail to walk on daily and Varty Lake nearby for daily dips in the summer. Within a few months of receiving the bad news, I began to tell everybody that I hated trees and my landlord smoked on the back porch. To top it off, the long driveway was never plowed, and I was constantly snowed in. I only got snowed in once, but I was making my case to pack up and go. I didn’t think there was any connection between Kevin’s impending death and my impulse to move yet again. I just gave my notice, packed up Gus and went to Toronto—the opposite direction of Ottawa, where Kevin lived. He had his own family to take care of him, so it wasn’t that. I wasn’t running away either. I’ve lived long enough to know you can’t outrun trouble. Trouble knows your forwarding address and will be snoring in the spare bedroom before you’ve unpacked the U-Haul. And I wasn’t leaving because I was afraid. Sick people have never frightened me. I had been sick as a kid, and it had granted me some strange superpower that meant I knew what to say when people were in crisis or in life-and-death situations. Or maybe it was because I had died so many times on stage.

I wasn’t running away as much as I was running toward a life I had given up years before. We had left the city when my kids were young, and even though I loved living out in the middle of nowhere, I wanted to go back and explore some still unrealized parts of myself before it was too late.

On my fiftieth birthday, my Aunt Mary sent me a card that said, “Now that you’re fifty, the days will drag, and the weeks will fly by. Happy Birthday.” With a wish like that, there should’ve been money in the card. But she was right. Those past nine years had gone somewhere, and it seemed like every time I looked up it was Thursday.

I packed up the dog and rented a spot one block west of bougie and one block east of despair, hoping an urban setting would give me one more kick at the can. Larger audiences and more auditions for TV.

Maybe the pursuit of my abandoned dreams was just my own personal shell game, but one thing was for sure: nothing new was going to happen to me when I was out in the middle of the woods, sitting on my porch swing, chewing a piece of grass.

Despite my protests to the contrary, my country friends thought I was making a terrible mistake. “Everyone is trying to get out of Toronto, and you are trying to get back in,” they said.

But I had tried to make living in the country work. I even tried to buy a mobile home. I reasoned it cost so little I could pay cash, live in a trailer park on weekends and have a flat in the city. The best of both worlds, I said. You’re not a mobile home person, friends said. You never know, I might be a mobile home kind of person, I said. It was the same lie I told myself about camping. I could be a camping person if it wasn’t for the sleeping outdoors part, and the mosquitoes part, and the communal bathroom part.

I had gone quite far along in the process; put down the deposit and signed on the dotted line, and I was about to pick up the keys when I noticed the sign above the entrance to the park. A sign I swear hadn’t been there two days before: “Welcome to Richmond Retirement Park.” Where did that sign come from? It was as if the word retirement had stars around it like this was a country everyone wanted to enter. It might as well have said, “Welcome to Death Row” because I cried out to Gus, “This cannot be how my life ends. In a trailer park?” I could just see the headline in our local rag, the Napanee Beaver: “Debbie Kimmett ended up exactly where she started.” Up until that moment, neither Gus nor I had any idea I felt so negative about retirement or trailer parks. But there we were. I went from living in a mobile home is an excellent idea to what the hell was I thinking in the space of about ten minutes. I withdrew the offer on the spot, cut my losses, packed our bags and moved back to the city.

As I barrelled down the highway with the shih tzu on my lap, I reviewed the close call: “Thank God I saw the sign when I did. Otherwise, where would we be, Gus? One step closer to death, that’s where. I think that old guy driving by on a golf buggy might have been the Grim Reaper.”

Whenever you start over, everything is shiny and new—worthy of a status update on Facebook. A short period when you look at even the most arcane things with the eyes of a tourist. Did you see that rock? That rock is historical. Did you know our founding forefathers rolled that rock up here from the States? It’s a short window of time before your eyes will adjust to the view and soon even the most beautiful surroundings will become wallpaper, pasted onto the background that you walk by on your way to work.

It had been years since I’d lived in an apartment building, smelling other people’s dinners. Hearing people partying and crying babies squawking at all hours of the day. All that noise was why I had left the city the first time. But all wasn’t serene in the country either: there, it was the sound of coyotes killing their prey that kept me up. Most nights it sounded like Khandar out there. After living in the wilderness for nearly twelve years, I decided that if I were going to wake up before dawn, I’d rather it be from the sound of human beings.

Back in Toronto, I was happy to hear people shutting apartment doors, going to work in the morning; at night, screaming soccer fans honking horns when their team won the cup, and rap music pumping from cars in the heat of the summer. I didn’t even mind fire engines racing by at three in the morning. All that urban energy made me feel like at any moment something could happen.

Within days, I knew everyone in the neighbourhood. I’ve retained the small-town quality of talking to everybody that has a minute to spare, even the ones who don’t. Over the years, I’ve developed a collection of guaranteed icebreakers: “Can I just say? Your dog is the cutest. What kind is it? A lab mix? Gorgeous. By the way, your shoelace is untied. I don’t want you to trip over your feet.”

I inherited this quality from my dad. He used to drive downtown waving at everybody like he was the mayor of Napanee. It would take him a couple hours to walk a block from the bank to his van. When he went to the local dump, he’d be gone all afternoon. No matter what a person’s station in life, after a ten-minute conversation with my father, they’d tell him their entire life story. Their wife’s name, that their kids don’t come home much anymore and how their sister hates her boss. Dad had a face that made people think he cared about them. He’d never say much but a silent man often appears wiser than he is. He would nod and laugh in the right places, and more importantly, he’d follow it up with action. He’d do anything for anybody. Drive a hitchhiker to his destination, pick a guy up from jail. Once, he followed a complete stranger home and fixed their broken toilet.

For the most part, people want to talk to me as well. It’s something about my face. That wholesome, well-fed farm face; a face that looks like I drink a lot of cow’s milk. A face that, when I was younger, I had tried to contour out of existence.

Right on cue, Preacherman interrupted my musings and yelled again, like maybe half the neighbourhood hadn’t heard his question the first time. “I SAID DO YOU BELIEVE IN ONE TRUE GOD?” I know this was likely a rhetorical question, but I found myself thinking about it—although the word “God” is the one I yell out when I stub my toe in the middle of the night.

I’d spent fifty years wrestling with that three-letter word. But it sounded like the God he was selling would have to be small enough to fit inside the lyrics of a country music song.

Let’s pretend for a second that I did answer him and say indeed I do believe in the one true God. How would that go? Would your God be the same as mine? Are you assuming I believe in Jesus’s dad? Or Allah? Or Yahweh? Tell me, sir: What sort of one true God are you looking for?

Over my lifetime, I’d bowed down at the feet of them all. Jesus, Buddha, Kali, Krishna. The real gods and the false. Booze, men, and Facebook. I had danced with witches, whirled with Sufis and explored The Power of Now like there is no tomorrow. After all that time and money, you’d think that Amazon would’ve delivered me a deity in which I could believe with complete certainty, but it had not. And any faith I had cobbled together over my life had been waning, ever since my brother was diagnosed with a glioblastoma tumour. Which is not one of those tumours. Not a my-second-cousin-twice-removed-had-a-tumour-and-drank-sheepurine-and-got-it-cut-out-and-now-she’s-fine tumours.

A GB tumour is aggressive. It doesn’t care about anyone’s spiritual credentials. It was like the landlord had given him notice and developers were coming in and tearing the building down. We could beg and plead and say he’d been a good tenant, but that kind of tumour doesn’t care. The wrecking ball was coming. My brother, who had always believed in the one true God, had less than a year to live.

But when a man on a soapbox screams at you, you know there is no point in giving him your spiritual resumé, because you can’t convince a zealot of a god-dang thing.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram