“Did you find it yet?” my 9-year-old son Zac poked his head around the door. I stopped frantically tearing apart my backpack, pausing in something near to blind panic. I shook my head.

The “it” was my wallet. The very-important-never-leaves-my-side-wallet. The wallet that had everything—my credit cards, Canadian and Chinese bank cards, cash in different currencies.

We were in Bangkok, Thailand with my closest friend, Jen. She and her husband Matt were both packing as we got ready to leave for the airport, and the plane that was taking us to Chiang Mai in Northern Thailand. Sitting up from my spot on the floor, I rubbed the back of my neck and surveyed the hotel room floor one last time.

I sat back on my heels and took a breath. This was only day two of our five week vacation through SouthEast Asia. Had I really lost all our money—and all of my access to our money—at the very beginning of our first big vacation? Warm devastation chewed along the walls of my abdomen, quickly making its way up my throat. How had I let this happen?

The day before, Zac and I had arrived at Suvarnabhumi airport. In my mind, I retraced our steps and pictured us walking right off the plane and up to a currency conversion stall. I knew, with sudden dread, that I had left it there.

I hadn’t even made it out of the airport without messing up. Without failing.

I shook my head. If I didn’t find the wallet, I’d need to borrow money and fly us both back to Wuhan, China. At least there we had our apartment and my Chinese bank account.

I thought of all our plans for the next few weeks. We’d been so excited to eat our weight in Thai food, to meet elephants up close, to spend a week lounging on the island of Koh Tao. It stung to think of how much I was letting us both down. I closed my eyes, willing the oncoming tears away.

It had been months since we’d seen Jen and Matt. I’d accepted a teaching position in Wuhan six months ago—and here I was, already welcoming them back to the disorganized experience of being my friend. Their kindness and patience never wavered, but this time the stakes were higher, because we were traveling abroad together.

As the four of us piled into a taxi, I told myself we’d find my wallet in the Lost and Found section of the airport, or at the currency exchange where I’d left it. I had to.

Becoming a single mother at the age of 19 had changed the plan a little.

I hadn’t exactly been bombarded with stories of single moms backpacking the globe with their kid. Until I’d moved from Canada to China—until I’d seen first hand the opportunities available to us—it hadn’t even occurred to me as an option.

Though my childhood hadn’t been typical—I was raised by a single mother myself—I was nonetheless heavily influenced by mainstream ideas and culture that kept me striving towards what I thought my life was supposed to look like.

The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, and Aladdin were childhood favourites. Every one of them showed the importance of first finding and then securing true love before being able to live your one true life (which, let’s face it, seemed to revolve around that so-called true love).

Before I was old enough to know what I wanted, my life path felt planned out. I’d internalized messages that a successful life meant going to school, getting a job, getting married, buying a house, and having kids—all in that order. Life instructions seemed to stop there.

Instead, my life had been more: become a single teen mom at 19, go to university at 21, have a few relationships that wouldn’t lead to marriage, graduate, and fail to find a job in my field.

The media and general society promoted a “normal” life that looked nothing like my lived experience.

I knew there were immense benefits to raising children single handedly—we were living proof of that. My son and I were living abroad, experiencing new cultures, reveling in ultimate freedom.

And yet the voice of the patriarchy still whispered in my ear: This is not enough. It will never be enough.

If I was honest, it wasn’t losing the wallet that was undoing me. Losing the wallet had simply allowed my fears about my inadequacies and shortcomings to rise to the surface.

They’d been there all along, planted throughout my childhood—well before I became pregnant. Made stronger and deeper throughout my son’s childhood, too.

As we approached Suvarnabhumi Airport, the gorgeous curves of the airport’s architecture no longer captured my attention as they had the day before. Grabbing my backpack from the trunk, I eyed the seats of the taxi just one more time before catching up with the other three.

We split up, agreeing to meet back in the same place in twenty minutes. As Jen and Matt turned left towards the Lost and Found, Zac and I turned right to retrace yesterday’s steps. The airport was still swarming with people traveling to see family or enjoy vacation during Lunar New Year, a holiday that marks one of the largest mass migrations each year.

There was a sense of excitement in the air. It was a time to celebrate, a time to travel, a time to be with loved ones.

For me though, it was simply a time for colossal failure.

As we navigated the people and silver luggage carts, snippets of Chinese phrases found their way to my ears, woven around the abundance of Thai. My eyes wandered over to a mother telling her daughter something. “Méiyǒu,” I heard her say as she shook her head, holding her empty hands up. Don’t have.

I glanced past another display of bright red lanterns and saw a desk labeled “Customer Service.” I hesitated, then changed course, wanting to cover all my bases. As I approached the attendant, she bowed slightly, her palms pressed together. I hurriedly returned the gesture.

“Excuse me, but is there anywhere else other than Lost and Found where I might find something I lost?”

The woman hesitated, unsure. As she gazed at me with dark brown eyes, I reminded myself to slow down.

“I lost my wallet here yesterday,” I explained, eyes stinging as I voiced the words aloud. “I have friends going to the Lost and Found, and I’m going to where I think I left it. But maybe things are kept at desks like this one?”

“I’m sorry,” she replied, her voice gentle. “We don’t have that here. If we are given anything, we bring it to Lost and Found.”

I nodded and thanked the woman. As Zac and I walked away and towards the currency counter, I wondered wildly if maybe it would be there, sitting on the counter where I’d left it. Hope flared irrationally.

I looked down at my son’s concerned face and gave his hand three squeezes: our traditional stand-in for “I love you.”

“Honey, if it’s gone, we’ll figure it out,” I reassured him, speaking past the boulder lodged in my throat. I couldn’t yet comprehend what figuring it out would look like. I couldn’t let my thoughts go beyond the fact that everything hinged on finding my wallet.

Zac gave my hand three return squeezes as we made our way to the currency exchange counter. When I asked the agent if they’d found my wallet from the day before, the man shook his head.

I swallowed, telling myself there was still hope that someone had brought it to the Lost and Found.

As we approached Jen and Matt ten minutes later, Jen looked at me and I knew. No wallet. I fought the irrational urge to go to the Lost and Found myself, to comb through every inch of this airport, to look through every last nook and cranny.

We’d run out of time. It was time to check in for our flight.

***

“And what about your plans to become a teacher?” My mom’s friend took a sip of her wine as others chatted around us in my mother’s living room.

I shifted baby Zac to my other shoulder. “I’m going to go to school in a year or so, when Zac’s a bit older.”

She raised her eyebrows and gave me a patronizing smile. “You say that now, but…” her voice trailed off, almost playful.

Anger flared, deep in my belly. I barely knew this woman. Who gave her the right to pre-judge me?

I thought back to a conversation I’d had with Zac’s biological father while still pregnant, before he disappeared. “We won’t be able to afford both of us going to school at once. I’ll go first and finish, since I’m already there. You’ll take care of the baby—you can go later.”

I’d been surprised into silence. As though it was settled. As though I couldn’t possibly have an opinion in contrast.

I blinked, staring again at my mother’s friend. She wasn’t the first to question my goals, to assume that becoming a single mother would limit me, to think that I might fail.

To believe that to become a mother would hold me back, instead of propel me forward.

When we finally stepped up to the check-in counter, I was infinitely thankful our passports hadn’t been in my wallet as I’d planned—my disorganization had done that for me, at least.

As the check-in attendant looked over our passports, I readied myself for the usual question: What is your relationship to each other? It almost always came. Several times, the question had been answered for us with presumption: Why are you and your brother traveling?

I knew many biracial families resent the fact that strangers assume their children are not their own. Yet it was always established by strangers from the get-go that Zac and I were somehow related, though my skin tone is light brown, while Zac’s lightly tanned skin means he consistently passes as white. Perhaps it was our matching sets of dark brown eyes that gave us away, or the fact that we were constantly interacting with our usual banter. Or possibly, a full-on tickle attack orchestrated by my son in the most random of places.

Still, this automatic assumption that we were siblings made it seem like even perfect strangers couldn’t be sure I was all that cut out for motherhood—or at least, not the respectable version of motherhood that was so widely expected.

I glanced behind us at a family of four. The mom looked put together, her hair pulled back in a tidy bun that showed off her small gold earrings. She pulled her Mulberry luggage alongside her, and I couldn’t help but glance down at myself. With my backpack and hoodie, I didn’t exactly scream “capable adult.”

I didn’t feel like one, either.

“Can I see the credit card you used to make the purchase?”

Startled, I looked up at the woman behind the counter, shaken out of my reverie. “Pardon?”

“I need to see the credit card you used to make the purchase online.” The Thai attendant repeated herself patiently, looking at me. I closed my eyes, devastated.

“I just lost my wallet—I don’t have it. Can we still fly?” I knew the answer instantly, watching her eyebrows crinkle together in sympathy as her hands stilled over her keyboard.

The woman shook her head, her shoulder-length black hair swaying. “I’m sorry, no,” she said, her fingers starting to type once again. “I need to cancel it. You will need to purchase the tickets again, but quickly—your plane leaves in 40 minutes.”

I felt a flash of anger at this ridiculous rule, promptly followed by an avalanche of disappointment at myself for putting us in this situation in the first place. Tears pricked the back of my eyelids, and I blinked them away. “With what?”

Maybe this was the universe’s way of telling me that I should have just stayed complacent: living in my mother’s basement watching reruns of the Gilmore Girls in my sweatpants, feet propped up on the armrest of our too-small couch. Maybe that’s where I belonged, I thought, throat tightening.

Who did I think I was? Five weeks of travel across multiple countries required a responsible adult to be in charge of things. Zac and I didn’t have one of those.

***

No matter what I did, it never seemed to be enough.

Whether it was going back to school for multiple degrees, keeping my son safe, or sharing loving and connected experiences with him. Whether it was raising him to be a feminist and a kind, empathetic person who wanted to help others, whether I traveled the world with him.

I wondered if there was another reality in which I wouldn’t feel like I was getting this whole motherhood thing wrong, in which I wouldn’t feel like a failure.

Was I the only mother who felt this way? Was it because I was a single teen mom, living outside the patriarchal preference of a two-parent heterosexual family?

Or could it be that all moms feel this way—whether they were viewed by society as acceptable or not?

“Excuse me…” the young woman, a fellow York U student, leaned across the aisle of the bus as I shifted my attention from my screaming toddler to her. I felt myself relax—she was about to offer help. Zac might respond to someone new. “…but can you get him to stop?”

Anger tinged my tone. “That’s what I’m trying to do.” I pointed out what I thought seemed obvious.

Today our favourite bus driver wasn’t pointing to cars for Zac to name, but sitting silently, trying to concentrate despite my son’s sobbing. It wasn’t as bad as the time Zac had been wailing at Union Station in downtown Toronto. I’d tried to get him his bottle while I read the schedule display, trying to figure out the track for our train. All of a sudden, a man had thrust his unshaven face into mine, eyes flashing. “Nobody wants to hear your kid. Shut him up,” he’d growled, then disappeared instantly into the crowd.

People could be awful.

To be fair, moments of nastiness were an anomaly. My two-year-old was typically a hit with strangers, students, and drivers alike—especially when wearing his dark blue hoodie, which announced him as a charming “Big Man on Campus”.

Over two hours later, without a moment of reprieve from the screaming, we stepped off our last bus, finally making it home from campus. Needing a break from the judgemental stares, I pushed the stroller with my still-wailing son into the washroom, locked the door, and sobbed alongside him.

As I stood in line with Jen at the airport, I looked over at Matt and Zac sitting on a bench with our bags surrounding them. Matt’s dirty blond head was bent toward Zac’s brown one, listening attentively with characteristic patience as my nine-year-old chattered away, no doubt about one of the characters in a game he played.

“You two should go,” I said, and let out a breath. “We’re not going to make it.” The line to get our tickets was moving painfully slowly.

“We have a bit more time,” Jen replied. “Let’s wait and see.” Her sympathetic brown eyes met my own, making me feel even worse. Why was I always messing things up? What was wrong with me, that I was so incapable?

“We’re going to have to fly back to Wuhan,” I said. “Cut it all short.” My voice felt heavy with disappointment, heavy with failure. Was this really how our first international trip outside of China was going to go down?

“Maybe,” Jen replied. “But I think you’ll figure it out. You usually do! And at least, hopefully, we’ll get our part of the vacation together!” Jen’s encouraging attempts had been falling flat, but now I smiled.

It had been a perfect idea to start our trips together. Following our time in Chiang Mai, the plan was to split up and go our separate ways. Jen and Matt to Myanmar, Zac and I to Cambodia, Vietnam, and possibly Laos.

Not that it seemed possible anymore.

As the line inched forward, I thought of my wallet. I had to let it go, which felt impossible. I couldn’t pull off the trip without access to funds.

The line began to move. Looking at the time, we knew it’d be tight—we’d have to run for the gate. I re-purchased the tickets with Matt’s MasterCard; we rushed through security and joined the last of the line at our boarding gate.

I pulled my kid close, my chest expanding in gratitude.

When I’d first decided to take Zac to SouthEast Asia for a vacation, there’d been a lot of opinions.

A family member’s voice reverberated over a mug of tea. ‘I’d never bring my children to an underdeveloped country.” Amidst my anger, I thought, ‘And I’d never bring my kid to the same Disneyland resort every year.’

I was tired of certain types of travel being deemed acceptable, desirable. Of some types of travel being seen to elevate as a status symbol, and others frowned upon, viewed as too dangerous. Too “other.”

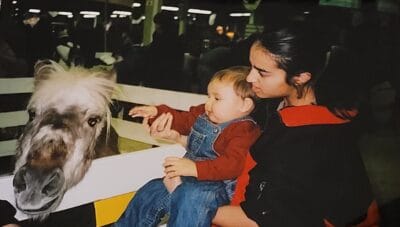

I moved to China and pursued travel because I wanted my son to engage meaningfully in history, to immerse him in experiences that would grow empathy, foster sensitivity, and offer numerous opportunities for human connection. I wanted to expose him to different cultures and languages, to gain different interpretations of the world, to foster a sense of adventure, to share experiences he might carry with him into adulthood: a love of travel, of history, of food, of architecture. Of all the world had to offer.

This trip was more than a vacation. All of these things were wrapped up in my pursuit of this way of life, in pursuit of these travels, in pursuit of this lifestyle.

And if I couldn’t do it, it would feel as though I’d failed not only at providing a vacation.

I’d feel like I’d have failed, yet again, at motherhood.

***

After the five years it’d taken me to get my two degrees, I’d spent two years trying to get a job teaching in an elementary classroom. Two years of resumes, of taking additional qualification courses, of trying to pay down my student loan of over $50,000. Two years of month-to-month contracts in fundraising, two years of not teaching, two years of being willing to take whatever I could get.

It hadn’t worked. I’d found out, too late, in my last year of university: the education field was overwhelmed. Too many teachers. Not enough jobs.

Almost ten years after becoming pregnant, and this is where I was. I’d spent all this time trying to follow a certain path, and it hadn’t seemed to want me. And if I was honest, maybe it’d never been meant for me. After all—I’d never stopped to question if it was the right one.

After the job fair that led us to Wuhan, I decided to push against the fear telling me to stay put, stay safe, and live orderly. I’d tried in vain to follow the societal script laid out for me, but had fallen flat with no career, no long-term relationship, and no home of my own.

It felt like wearing a pair of jeans one size too small. I could keep trying to make myself fit, but did I want to?

I’d decided there were other ways to live a good life and be a good parent. That I could reject the prescribed path. The “acceptable” way of life that constantly made me feel like I wasn’t enough.

Living abroad, roaming the globe—this was another lifestyle, an alternative I hadn’t considered before I’d stepped into an international job fair. A new path that gave a somewhat acceptable way out of “the norm” that was proving so difficult for me to adopt.

But what if I couldn’t be a capable, conventional parent back home—or a capable, non-traditional parent abroad either? What would be left to me if I failed at both?

Following the plane ride and a taxi ride, we arrived in the centre of Chiang Mai. The four of us hoisted our backpacks and began walking.

Chiang Mai was bustling and vibrant, surrounding us with smiling faces. Had I ever been anywhere that was this warm and welcoming? Complete strangers on the street seemed like they knew me personally, warmly greeting me to their city. I smiled at the sight of the tuk tuks, little open-air carts that were a quick and cheap mode of transportation. I’d seen some in Wuhan, but these were completely different—these were painted brightly, and fun, and cute. I couldn’t wait to get on one.

The chatter of others surrounded me. Some were connecting with those they knew, while others were ordering from stands serving delicious-smelling street food. Pad thai, grilled fish, bubbling soups, and ohmigod—something called mango sticky rice that became an instant obsession.

We walked up a street that wound away from the centre and up a hill. After a few stops at full hotels and more time under my heavy backpack and the hot sun, tiny rivers of sweat grazed my ears as a sure sign that the novelty of backpacking was beginning to wear off. Glancing over at Zac hunched under his bright blue backpack, I braced for the complaints that I knew were coming, and wondered if I’d need to carry his backpack to give him a break. God, I hoped not.

We found a hotel twenty minutes later. After checking in and enjoying drinks on the front patio, we decided that I’d e-transfer money to Matt, and he would make daily withdrawals from the ATM around the corner.

Still, that money wouldn’t be enough to sustain us over five weeks.

Later that evening, I was able to request an emergency credit card from my bank.

The card came with extreme limitations, but it also meant we’d continue with our trip largely as planned, instead of booking an early flight home to China.

Days later, I looked out the window at the scenery whipping by. My emergency credit card had arrived the day before, and we were on a train heading back to Bangkok. From there, we were headed to Phnom Pen, Cambodia.

I recalled the moment I realized I’d lost my wallet and might have to cut our adventure short, and my gut couldn’t help still twisting in residual fear. The fear of thinking I wouldn’t be able to do this. That I wasn’t responsible enough, organized enough, good enough, to pull this off. To give us an incredible experience. To keep my son happy and safe.

To live differently than others expected was a constant navigation. To meet my own expectations, though—that was another thing entirely. That exploration wasn’t over.

I thought back to a few days ago, my son’s laughing face turned towards the trunk of an elephant as it sprayed water all over him. Then Zac had filled a bucket with water and chased me around the river, giggling when I stumbled and fell in.

A few seats away, my son let out a peal of laughter. I smiled, eyes drifting to where he was sitting, next to another little boy who was also traveling with his parents. The parents smiled back at me, our eyes meeting. The two boys peered together at a game, chatting excitedly.

I felt a warm glow of joy spread through me, overriding my anxiety. I sighed in satisfaction, eyes drifting back to the window.

It would take work. But I’d figure out my own path.

Natasha Steer is an educator and writer who lives with her son in the Greater Toronto Area. She became a single-lone mother at the age of 19 and has traveled to over 50 countries with her teenage son. She writes about the intersection of feminism and motherhood, creativity, and travel. You can find her on Instagram @natasha.steer and on Twitter @NatashaJSteer.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram