No assignment has brought me greater joy this year than this one. Watching Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street filled me with feelings of comfort and wonder, and allowed me to float back to some of my warmest chapters of childhood.

The doc begins in NYC, in 1981. The film opens with a birds-eye view of the set, modelled after a block in Harlem: the wide and inviting brownstone steps, Oscar’s garbage can to the right, Big Bird’s nest in the back alley and Mr. Hooper’s store, which is stained and gritty, but colourful—an accurate reflection of most corner stores in New York City at that time.

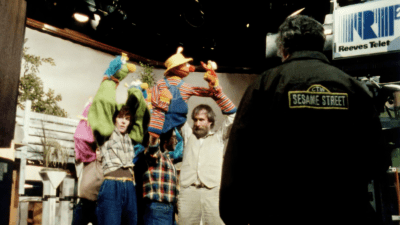

As the camera pans down, to street level, we see a mix of small children, muppets (with sweaty puppeteers beneath them), and a crowded set of camera crew, some with cigarettes hanging from their mouths. This is where the magic happens.

“Sesame Street came out of the civil rights movement and was started by activists who wanted to change the world, and wanted to revolutionize television, and reach inner city kids…and do all of those things,” says Director Marilyn Agrelo (AN INVISIBLE SIGN, MAD HOT BALLROOM), who described working on this film as an absolute dream job.

Street Gang was inspired by the book Street Gang: The Complete History of Sesame Street by Michael Davis. While the book tells the full story, covering fifty years, the documentary focuses on the first 20 years of Sesame Street—the origin story.

It’s a fascinating story that began in 1967 with a few impassioned individuals exploring the possibility of TV, and asking themselves: Can children’s programming be both enthralling and educational? Can the TV medium teach kids how to read? And how can we make a show that will reach the children that need it most?

Sesame Street was funded by the US government to help literacy and help close the learning gap, so that all American children entered Grade 1 with fundamental knowledge about reading and counting.

“The US government gave the producers of Sesame Street 8M which is equivalent to 57M dollars today. This would never happen in this day and age,” says Agrelo, who describes those early years as experimental and daring. “When it first started, the USA was embroiled in the civil rights movement and revolution, and this is very evident in the show. If you remember the documentary scene with Reverend Jesse Jackson leading the kids in like a Black power chant, you would never see something like this on Children’s Television today! Things have gotten very politically correct and things have gotten very safe. It’s the way society has evolved, especially in regards to children.”

I was so moved by the doc that after watching it, I purchased a few classic Sesame Street episodes from the early 1980s (when I was their target audience), and spent a Saturday night watching one after the other, with glazed eyes and wide grin. I was able to sing along to sketches I hadn’t seen since I was five years old, but somehow remembered all the words.

Revisiting Bert and Ernie at age 41 lit up parts of my brain that I had forgotten about, and had me laughing out loud. Those hours on the couch, reconnecting with Grover, Gordon, and Maria gave me a blissful high, I had found the truest form of escapism since the onset of the pandemic. My partner, who grew up in Edinburgh and who didn’t have Sesame Street, was confused and a little alarmed at my late-night binge, asking me a few times, “Are you still watching Sesame Street?”

After watching a few retro Sesames, I decided to check out a modern-day episode. The show is still beautiful, but the vibe is noticeably different. Big Bird isn’t the same without Caroll Spinney, who passed away in 2019, and the humour is less sophisticated.

“The humour that was written for the show early on was really aimed at adults. It was political satire, social satire, they wanted to bring in the adults so that mothers and fathers would love to see the show with their kids, and that way the kids would learn more effectively. Today it skews younger, and doesn’t get tied into any controversy at all,” says Agrelo. As cute as he is, I blame Elmo. But but at its core, the Sesame Street mission remains true. “What Sesame Street has always maintained is to try to help kids understand the world they are living in.”

Agrelo shares how Sesame is evolving its curriculum to talk about race head on, rather than just imply that we’re all equal. “They’ve got little segments now where muppets are holding protest signs, really simple protest signs, but it’s a way to explain to kids when they see these complicated things on the street, and in their world, to try to bring it down to their level, to help them understand the world they live in. They do that magnificently. I would say that it’s just a little less daring than it was back in the early days.”

It was groundbreaking, wildly popular, and while it was made for Black kids in low-income homes, it appealed to all children. “There were a lot of shows that talked down to kids, and we really didn’t want that,” says Sonia Manzano, who played Maria from 1971-2015. “Jon Stone thought that you could have a kids show where adults wouldn’t run to the doors as soon as it was on.”

The writing room included a mix of activists, TV writers, educators and childhood psychologists. Everyone understood the power of advertising, and recognized that children were singing jingles and identifying products at the grocery store, so they knew that if they used the same techniques—catchy songs, repetition—they could sell kids on the alphabet. But it went much deeper than that, and there’s a particular quote in the doc from archival news footage that sums up the mission beautifully, “Sesame is what television could do if it loved people instead of trying to sell to people.”

“There was the cognitive stuff… numbers, letters, and all those things, but equally as important, maybe even more important was that Sesame Street was a neighbourhood where people of all races—kids, adults, and monsters—lived together,” says Christopher Cerf, composer, lyricist and writer, who is one of many of the original creators interviewed in Street Gang, who received a lawsuit for writing the beloved “Letter B” song, cheekily inspired by The Beatles’ “Let It Be”.

Seeing Sesame Street get it so right in 1969, it’s hard to understand how society still hasn’t caught up to what they achieved over fifty years ago. But in a way, we’re living through a very similar moment, which is why the doc hits so hard. “When Sesame Street first came into the scene, the United States was going through big upheavals: the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War, protests in the street,” explains Agrelo. “With BLM, and all these things… it’s like a second awakening. Because of the pandemic our world has been turned upside down, again. It seems to be a perfect moment to tell this story because it’s a reminder of what good can happen. We’re in a very similar place.”

Today, Sesame Street has muppets performing in Syrian refugee camps. Julia, is the first character with autism, to help more kids see themselves on TV and understand that people move in the world differently, and learn differently. Recently, audiences were introduced to Wesley Walker and his father Elijah—two African American humanoid Muppets created to help families talk about race, and celebrate race. “The power of art is such an agent of change and when children are exposed to what art can do, profound things can happen, and I think Sesame Street is one of the most shining examples of that.” It sure is, and Street Gang captures its heart and soul.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram