Miali-Elise Coley-Sudlovenick’s mother is Inuit and was born in an outpost camp outside of Kimmirut. Her father is from Mandeville, Manchester, Jamaica. Miali was born in Iqaluit (or as she reminds me, was called Frobisher Bay at the time of her birth), and her first language is Inuktitut.

Her parents separated when she was quite young, and while she visited her father annually, and he always sent books to remind her of her Jamaican roots, Miali grew up surrounded by her mother’s family and lived in an Inuit community—she didn’t identify as being Black. But when George Floyd was killed by police this past May, and the Black Lives Matter movement gained worldwide momentum, Miali began to look at everything differently.

“I’m still beginning to understand my own identity, in terms of how I’m placed in society,” she tells me over the phone, from her home in Iqaluit. When the news broke of Floyd’s death, Miali—like so many—had a visceral reaction. “There was this tightness in my chest. He could be my father, or my uncle. It struck something in me. His death started to open up a lot of things that I hadn’t really thought about,” she says, holding back tears. “My father, and his Black family, are from Jamaica, but they were brought to Jamaica at some point. And so these kinds of things were realities that I started to realize that I was part of.”

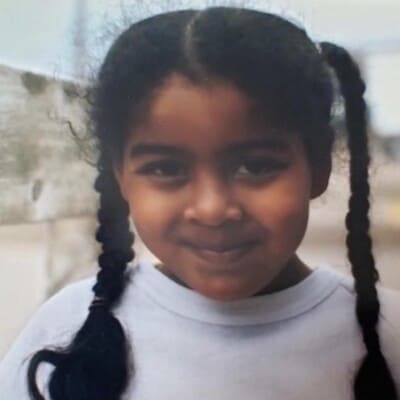

Miali as a young girl in Iqaluit.

She began looking at her family history closely while also examining her own life with a new lens. The exercise had her rewinding to uncomfortable moments from childhood. “I had a lot of friends and a very supportive network, but there were always kids who would go out of their way to push me, or I’d have scratches on my hands, pinch me, pull my hair. I had experienced racism, but I was so not identifying as a young Black person that I somehow didn’t take a lot of those things personally. I’m thankful, in a way, that I was able to get through a lot of it blindly,” she says.

During the nineties, in her teenage years, Iqaluit became an increasingly popular destination, especially after being selected to be the capital of the new territory of Nunavut in 1995. The population began to grow and there was an influx of tourists.

Miali in 1999, when Nunavut became officially recognized as a territory.

People new to the north, who noticed the colour of Miali’s skin, prodded her for answers. “When Iqaluit became this hotspot, we had a lot of new people and people couldn’t place me, and they’d be like ‘Where are you from?’. When I said I was from here, they’d be like “But where are you really from?’. I was always having to explain myself. I never understood that I didn’t have to do all those things, to go out of my way to explain myself.”

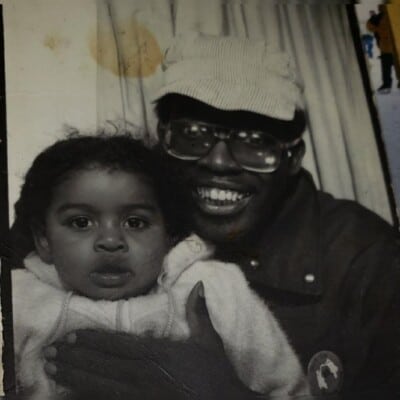

Now, there are many Black families in Iqaluit and Nunavut has a Black History Society that has organized events this February to celebrate Black History Month. The African and Caribbean Association of Nunavut is also a growing community, founded on the principles of Pride, Strength, and Unity. But these types of groups and spaces weren’t always around, and Miali guesses that when her father first moved from Toronto to work in Iqaluit, there were maybe 10 Black people. Discovering her Black identity and culture wasn’t easy.

Miali as a baby, pictured with her father.

Around the same time this summer when Miali was digging through her past in an effort to better understand herself, Mumbi Tindyebwa Otu, Artistic Director of Obsidian Theatre in Toronto, began her own exploration of identity by looking to the future, asking: what is the future of Blackness?

Like Miali, George Floyd’s death and the Black Lives Matter protests that reverberated around the world deeply impacted Mumbi, and compelled her to ask questions, and explore deeper. She began putting together the idea for 21 Black Futures, or 21 powerful monodramas that imagine what a Black future looks like. She reached out to Miali, hoping she’d contribute a perspective from the north.

Miali with her two daughters.

Miali was hesitant to participate, because she has two young daughters that require her undivided attention, but the idea of connecting with the larger Black community, and tapping into a network of Black artists throughout Canada, was incredibly appealing. “There’s a sense of delight. It’s yummy and delicious. Being part of something bigger…is what I kept thinking about because I’m in my own little world up here.”

Miali’s play Blackberries premieres on CBC Gem tomorrow. Much like her own pursuit of self-discovery, the play follows a young woman’s search for identity. Effie’s father is Ghanaian and her mother is part Black and also has ancestors that are Inuk. Effie travels up north to meet her family and after attending the funeral of her grandma, she has a profound cultural experience while participating in something. “For me it was the connection of the intergenerational pieces. The communication between mother and grandmother. She’s relating to family in terms of how she fits in, and how she gets to participate, and how she gets connected.”

Miali riding the waves with her mother and eldest daughter.

Blackberries draws a lot from Miali’s own experience, but is different. Instead of flying north to meet family, Miali has made trips south to Jamaica. “As much as I love the north, I do love that heat! I miss that sunny beach, fresh salty water, and the food—the food tastes so fresh. We have food right off the land here, and it’s amazing, but we don’t have trees,” says Miali, who takes a moment to compare the two cultures. “The laughter – there’s a similarity between our Inuit culture here, and Jamaica. We laugh easily, we enjoy our food, eating together and making memories.” While she loves to dream of a return trip (especially on -27 days) Iqaluit will always be home, “This is where I feel safe and connected, and where I can best contribute.”

Being part of 21 Black Futures has been a phenomenal experience for Miali, and her play, directed by Alicia Harris (whose film Pick is currently in the Oscar race for Best Live Action Short Film), and acted by the radiant Adeline Bird, is one of the many pieces in the epic project that’s getting a ton of buzz.

Miali and family enjoying a tow in their new qamutik.

Connecting with the larger Black creator community was a truly unique and empowering opportunity, particularly so for someone who lives 2,337 KM north of Obsidian Theatre and CBC headquarters. “I didn’t realize how much I needed to feel a part of something that I didn’t even know I was allowed to be a part of. I’m so thankful for that.”

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram