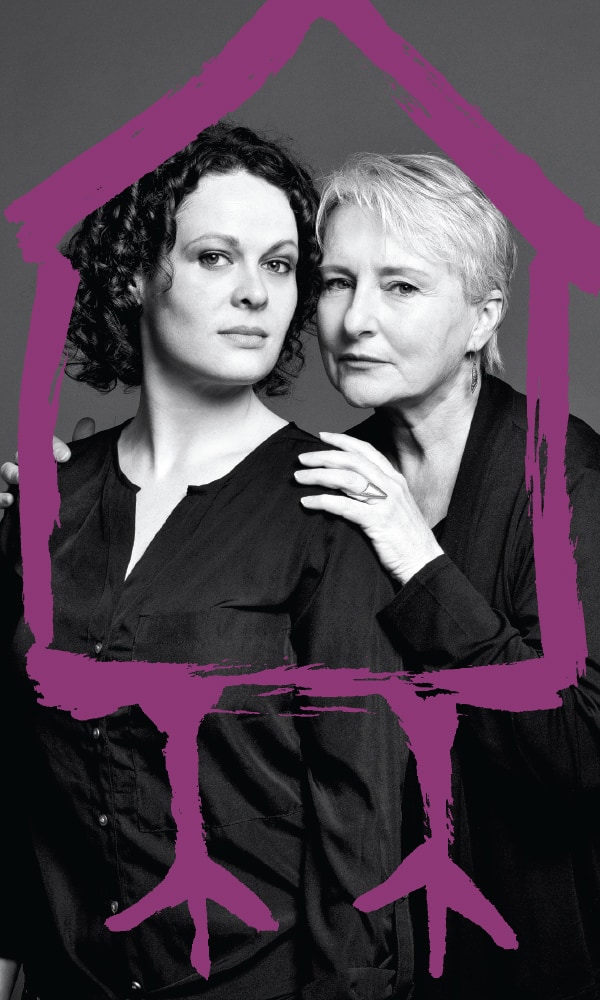

From the Dora Award-winning mind of Kat Sandler, Yaga was inspired by the story of Baba Yaga, the hideous old witch who lives alone in the woods grinding the bones of the wicked.

In Yaga, Sandler takes us on a comedic journey filled with feminism and witchcraft. There’s a gruesome murder, an affair between an older woman and her much younger student, and the key question: what happened to his bones? Yaga provides a vivid backdrop to an exploration of aging and sexuality.

We asked Sandler about the play this week.

SDTC: What was your first introduction to the Baba Yaga figure? What about her appeals to you?

KS: I have always been fascinated by stories, legends and myths. Like lots of millennials, I was raised on a steady diet of cookie-cutter fairy tales and prince-rescues-princess-from-wicked-witch narratives, so when I first came across Baba Yaga in some anthology or another, I was struck by two things: the imagery of her chicken hut and preferred method of travel/bone grinding (mortar and pestle), and the fact that she had a name. Witches are so often defined vaguely by colours, geography or their protagonists (i.e. “White” or “of the West” or “the one from Hansel and Gretel”) but here was a witch powerful enough to be remembered for how she operated, not just how she got shoved into a an oven or poisoned an apple that one time.

I love that no two Baba Yaga stories are the same. She’s usually described as old and ugly, and sure, sometimes she kills people, but she helps them too, when she wants to. Across the globe she’s seen as everything from monster to a quest donor, wise woman to a goddess, trickster to saviour and everything in between. She’s this morally ambiguous, complex female character— a villain and a protagonist, an antihero who does what she wants in the woods and refuses to be defined or labeled as one thing, and I think that’s why she’s so resonant with women today.

When you set out to write this play, what was happening in your life?

I had the idea for Yaga a few years ago. At the time, I had been watching a lot of crime shows and thrillers. I loved the formula: mystery, misdirection, twists, high stakes, then catharsis. I wanted to see if I could create a story that could play with that formula while at the same time breaking down the form in a way that only theatre can do.

Around that time I also remember having an argument with a few male pals—this was pre-#MeToo—about how women should be/are often portrayed in theatre and film and television. The crux of it was that if I wrote a female character who did something really despicable, I was saying that all women were capable of doing that bad thing, the implication being that because women are inherently good (in theory) I should write them as exclusively moral characters. Fuck that. Male antiheroes (Dexter, Walter White, Macbeth etc.) get to do bad things and still be considered fascinating, watchable and even good… I wanted to create a female character that existed in that morally grey area in the same way, and examine how our perceptions of the bad things she’s doing change because of her gender and motivations.

I had also been speaking with a friend, an actress and we got into a discussion about aging. She said after she turned fifty, she experienced a time in her life where people just stopped “seeing her.” In the period that followed maidenhood and motherhood (both traditionally-useful-to-society-stages) she felt invisible. As a society we tend to condemn age rather than honour it, and this is especially true of the arts, where we have such a wealth of female acting talent, especially women over fifty who are criminally under-used in new play development. I wanted to create this part for that demographic.

We don’t talk about sex in relation to aging much; especially when it comes to women. Why are we as a society so seemingly opposed to older women being sexual? How can we move the conversation forward?

I think we can move the conversation forward by having it. Women don’t stop having sex after sixty. They don’t just suddenly turn into grandmothers, doctors, and the occasional high-flying lawyer, which is how they’re often portrayed onstage and onscreen.

I think we’re so seemingly opposed to it because sex gives older women power—not the idea of manipulating someone with sex, but owning sexuality and being comfortable in one’s skin and desires, which leads to confidence. And the idea of older women continuing to have not only that power but having experience and knowledge that comes from the life she’s lived really scares men. After all, historically what we call a witch is just someone society has decided it’s scared of, and what could be scarier than a powerful, sexual, intelligent older woman making and living by her own rules?

There’s power in passion, experience and motherhood all of which are directly related to sex, and I think there’s power in re-defining how we talk about sex as we age.

What was the biggest challenge in putting this play together?

Whooo boy! The biggest challenge was that this play (and production) is really different from what I’ve been writing and directing for the last few years. It’s non-linear—usually I write plays that take place in “real time,” but this one plays with flashbacks and scenes that happen out of order. It has multiple locations—the last few shows I’ve done have been set in ONE place, so we were able to really detail the sets to be natural, but Yaga takes place in over ten locations—from the woods to an interrogation room—so on a direction and design level we had to work really hard to differentiate them cleanly and transition in and out of them quickly. The actors also play multiple characters. We’ve got three incredible actors playing fourteen parts, which is a challenge in the writing and directing as well as the acting. In a whodunnit, you want even your small characters to be memorable.

I’ve also never written a mystery or thriller, and the rules are very different. It’s funny in parts, but it’s definitely not a flat-out comedy, which is how a lot of people think of what I do, though I would say that I use comedy to explore dark subjects, which I’ve also tried to do here.

What do you hope audiences take away from it?

I want audiences to think about the ways we talk about and label women. I’d love for older women to get to see a powerful and exciting representation of themselves. I’d like to give a voice to the wicked old witch, a nod to the idea there’s power in re-telling the stories men have told about women, but from our perspective, in our own voice. And mostly, I’d like to tell a really fucking great story.

Yaga runs in Tarragon’s Mainspace (30 Bridgman Avenue) until October 20. Get tickets here.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram