I arrived at TIFF Bell Lightbox at 8 a.m., just a little before the crowds would start to fill all corners of the building. I was early for the #ShareHerJourney panel, taking place on the second floor, and aside from a handful of orange-shirted volunteers and theatre employees, the only other person around was a woman my age, standing alone. She had a laminate hanging around her neck, but I couldn’t decipher if she was press or industry.

“If it’s not going to start for another thirty minutes, I’ll go grab a coffee downstairs,” I told the front-of-house staffer, who, even at 8 a.m., appeared frazzled and anxious for what the day may bring.

Overhearing me, the woman approached me and quietly asked, “May I join you?”

“Of course!”

By the time the escalator reached the lobby, I had already figured out a few things: she’s a filmmaker, and her first feature film was having its world premiere tonight. I was curious to know more.

We sauntered into O&B Canteen, where a queue at the coffee counter already had a dozen or so people, dressed mostly in black (the standard film industry uniform). For once in my life, I was happy to wait, because it meant I could ask more questions.

“The premiere of your first feature film… This is a very big deal! Do you have family coming?”

“My sister is shooting a film in Macedonia, but she’s flying in for the night. She was the cinematographer for Zana.”

“That’s amazing!”

I can’t recall exactly how our conversation unfolded as we stood in line for coffee, but like a detective, I began gathering up the facts in my mind, trying to fit the pieces together. Her name was Antoneta Kastrati. She was from Kosovo but lives in LA. Her film Zana is about a woman whose daughter was killed in the Kosovo War, and years later she is pressured to have another baby, but her PTSD is menacing; she doesn’t want to bring a child into this world.

“There are a lot of dreams in the film, because I have nightmares,” Antoneta shared with me.

Sensing that she had lived through the war, but nervous to ask outright, I reframed my question: “What made you want to make this film?”

“My mother and sister were both killed during the war,” she told me.

“I’m so sorry.” I was at a loss for words, and I felt like this conversation shouldn’t be happening as we continued to shuffle sideways to the take-out counter. It was too personal, but I continued.

“Were you living in Kosovo when that happened?”

“I was eighteen. That day I was in the woods, where I’d go with friends to hide.”

I did the math in my head and realized we’re exactly the same age. I started having glimpses of my first year at university in Montreal, running from bar to bar. Carefree, full of possibility. My mind jumped to images of this forest she talked about. Would they hide in the trees? Were they lying still, scared? Did they read while they hid? Why did she decide to go that day? What happened when she arrived home?

We paused for a moment to order our coffees. We each ordered the same thing: drip, dark roast. (I am still cursing the fact that I didn’t offer to pay for hers. I was a bit stunned. Also, it wasn’t even 8:15 a.m., so I was still waking up.)

We paid and began to stroll back into the TIFF Bell Lightbox lobby, moving a little differently than when we first stepped onto the escalator to go down. Slower. I became more careful with my words, my movements. We were no longer strangers—I knew too much.

I discovered that her husband was the producer of the film, not because she told me, but because when I asked her for her business card, she accidentally passed me his.

“Casey Cooper Johnson?” I read as a question, holding the card in my hand.

“Oops, that’s my husband’s card. He’s the producer,” says Antoneta.

I asked her how she met him as she continued to dig in her knapsack, looking for her cards, cursing that she can’t find them.

“Don’t worry, I can just take a photo of your pass. How did you meet your husband?”

They met in 1999, when he arrived from California as a volunteer to help with war relief efforts. Soon after meeting, they began experimenting with documentary films, which eventually led them back to California, where Antoneta furthered her craft at the American Film Institute.

I didn’t say it aloud, but I couldn’t help but think how beautiful, and tragic, their love story is. I asked her if she has children. She told me she has two daughters; I showed her a photo of my son. The bond of motherhood brings us closer.

Finally we got to the line, waiting to enter the event. The floor that was quiet just twenty minutes before was now bustling with activity.

“Are there any tickets left for your premiere?” I asked.

“I think a few.”

Following the #ShareHerJourney event, I said farewell to Antoneta and told her that I will come to her screening. I don’t know if there are, in fact, any tickets left, but I was determined to go. I would find a way, and lucky for me, after a trip to the box office downstairs, I was able to purchase one of the last remaining same-day tickets.

Twelve hours later I left my house and began my 30-minute walk to the theatre. It was dark out, and the Saturday night streets were overflowing with twenty-somethings spilling out of bars. I called my mother as I walked along Queen West and told her about my day, about Antoneta.

Back at the Lightbox, I decided to get some popcorn, and settle in. The TIFF Discoveries Programmer, Doreta Lech, introduced the film and brought Antoneta up on stage. She was wearing a black floor-length dress, her makeup was done—I was so happy for her.

She pointed at an entire row full of cast and crew who had flown in from Kosovo. Zana is the first film from Kosovo to ever be shown at TIFF, yet another fact that adds to this tremendous story that I was privileged to witness.

I won’t get into how powerful the film is, because that is another story entirely, but suffice to say that I wasn’t the only audience member with tears streaming down my face as the credits rolled.

Since seeing the film two days ago, Zana is constantly on my mind. In particular, there’s a scene of a memorial, where all the pictures of people who’d died in the town are displayed on a wall, except those whose photos were lost during the war. Knowing that Antoneta’s house burned down, I can’t help but wonder if she lost all her photos, and it is one of the questions I asked her when I sent her a note the next day.

She responded quickly: “Ours didn’t burn when our house burned down. We were taking some albums in our backpacks every time we went into hiding. But it happened to a lot of families, and it was something that touched me deeply, which is why it was in the film.”

Antoneta doesn’t think that making this film will stop her nightmares, but she does hope that it will get people talking more about the real affects of war, including the ones felt twenty years later.

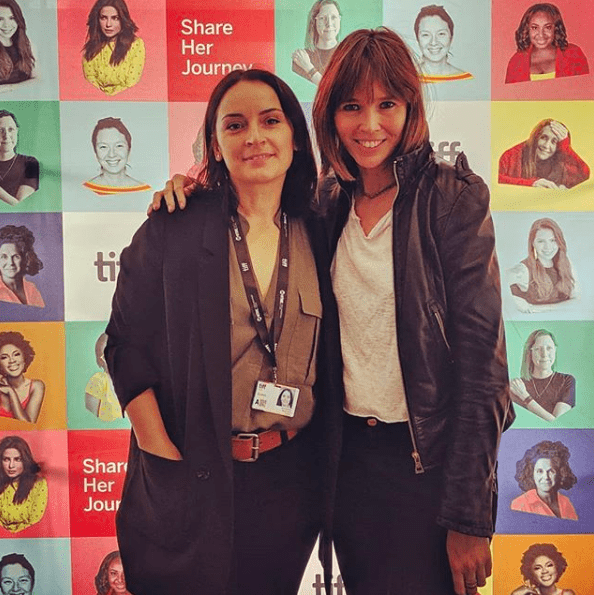

Antoneta is part of a burgeoning movement: the first generation of female filmmakers to come out of Kosovo. Her sister Sevdige is the only female cinematographer in Kosovo. Zana is dedicated to their mother, Ajshe Kastrati, and sister Luljeta, who both died June 10, 1999. I was honoured that Antoneta shared her story with me, and I wanted to #ShareHerJourney with you.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram