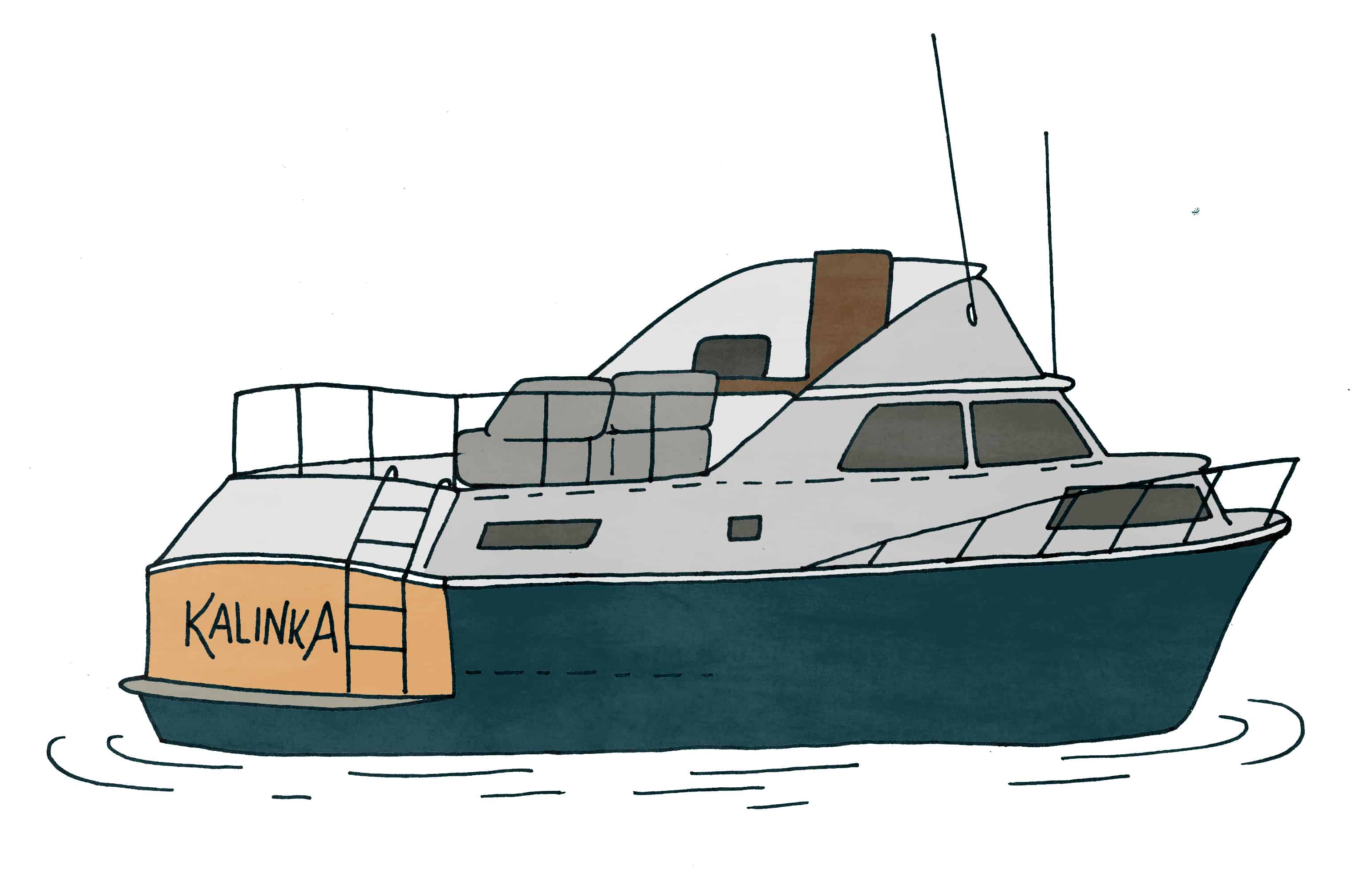

Melanie Janisse-Barlow is a poet, artist, and writer who splits her time between a rum-runners era house in Windsor’s Old Walkerville and a houseboat docked beside Ontario Place. We’re posting installments from Janisse-Barlow’s new memoir, Kalinka. Candid, raw, and full of references to our beloved city, Kalinka is a collection of stories about a woman, a man, and how life on Kalinka, their houseboat, has shaped their journey. We’re excited to share Janisse-Barlow’s writing with you and also delighted to pair with local illustrator Emily May Rose. Read previous installments here.

“Here she is.”

“Jesus. She is huge, and blue.”

“Yup.”

We stood there for a moment, fogging our breath into the winter air. Kalinka was a poem that waited for us this whole time. A wooden form. I ached towards her before I even knew her—something impossible, something kind in the face of a world tightening up like a drum with suburban houses and good jobs. Her hull is a royal blue. Her name is painted in white block letters on each side of her prow—both in English and in Russian. I am most in love with her old mahogany transom, nestled up against some trees, with the old gold leaf letters and the teak swimming platform.

What is a revolution? Is it a boat?

She is mahogany. There is something about her old wood that yearns for our hands. She wants us to give ourselves over to her material. She begs us to love and respect ourselves and to reflect that in the ways we use our hands, now that we have met. The worn, blue tarp flaps in the cold February wind, begging us to unwrap her. She is a lopsided present. She is a new pair of glasses.

Andrew disappears for a few minutes. I walk up close to the hull and run my hand along the royal blue planks bared to the winter. I watch the cheap plastic tarp dance in the gusts and listen to my heart beat deep inside of me. She is majestic—an aging beauty, like Havana or Warsaw—towering over me. Andrew comes back with a tall ladder and finds a place where the tarp is loose. He negotiates the ladder between the hull and the tarp, giving it a few good kicks to sink it in past the snow for traction.

Andrew shoves me—mink puffed—into the small gap between the boat and the tarp. I pop through onto the deck, with only a few feet of room to crawl along. My face is cherried from the winter wind. I am a giant in a strange blue-hued tree fort. Eventually, I will have to figure my way back down the treacherous ladder, mounted on slippery ice. I am keenly aware of the nagging fear of descending. Why was it so difficult to savour the moment? Portals are always chased by a nagging guilt, fear, distractions. I shake the future off and crawl over to the door into the boat. I lift the hatch, sweating again in my giant coat. I swing the door open, crawling back a bit to make room for its trajectory. The mahogany stairs and beautiful curved rail appear in front of me. I realize that I am holding my breath and remember to exhale. Her crooked land onto her cradles has me standing skewed from the ground. I immediately feel this new perspective take hold in my inner ear. In my body.

The smell coming from inside of the boat touches my nose tenderly. It is the smell of old plastic, sun burnt and crisp and of air held in somewhere made stale with time. I close my eyes and breathe it in. I see the barns at Goyer’s Marina, where I used to play as a child, strung with old antiques and slinking cats. I see the abandoned book shop in Detroit that I had broken into in my twenties, with its dripping ceiling raining onto rows of books on crumbling shelves.

I hold onto the curved mahogany rail and swing my feet onto the stairs. Once my feet find the floor of the main salon, I glimpse around, seeing my blue-hued face in the covered windows.

I stand there for a few moments before Andrew follows me in. These moments begin a trajectory of questioning. They are a few still moments, but are stoking something in me that gathers momentum. It is as if a prayer is said on my behalf granting a deep permission to forget the small injuries of life. To move on from the old pain, and the old messages and into the very space I am standing in. Here, no one polices my joy. The gatekeepers are left behind, where there are fences and pecking orders. Where their work has truck. Here, the sewn energies dissipate, the stupid tricks do not work. I am in a mysterious place where there is no history, no adherence to systems. There is only potential meeting material for the first time. In this very moment, I acquire the means for a permanent revolution. The blessed realm of suspension.

Andrew comes down the stairs behind me and wraps his arms around my waist. I taste truth like a supernova. The flavour of this explodes in my mind like a pomegranate seed would in the mouth, fierce and gorgeous. The automatic quality of my grief splits open into a long yearned for joy. I point over to the the shelf above the galley, to an old 1960s ceramic mug with blue line drawings of sailboats along the cream enamel.

“Look. It’s the exact same cup I just gave you for Christmas. We have to get this boat so that we have the matching set.”

I turn to Andrew and hold his face in my hands. We smile at each other in the blueness. We share in the food of the moment. It tastes like a supper of rising novelty. We have in the moments spent in the odd blue light—me holding the strange old ceramic mug in my hands—adjusted to what is. I know later will have me tractioning to the material world, so I savour floating above the ground in this vessel.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram

We’ve gathered

We’ve gathered

We’re giving aw

We’re giving aw Our Artist of the Month @ashleighrains spe

Our Artist of the Month @ashleighrains spe